Through the lives of two young people in 19th century China, Gene Luen Yang provides a powerful look at the dangers of fanaticism and the difficulties of faith.

Without a lot of heat or noise, Gene Luen Yang has eased himself into the top flight of graphic novelists.

He made his first real impression in 2006, when his graphic novel American Born Chinese (also published by First Second) won not only an Eisner Award but also the American Library Association’s Printz Award (for excellence in young adult fiction), and was the first graphic novel to be nominated for a US National Book Award.

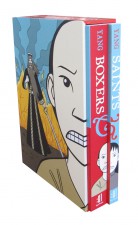

His latest work, the linked books Boxers and Saints, tells the story of the Boxer Rebellion in China at the turn of the 20th century, from two individual viewpoints. It’s probably worth flagging up here the fine job done by the books’ designer, Rob Steen; the covers (and spines) fit together, reflecting the way the two volumes and their protagonists interweave, as well as suggesting the yin/yang theme that plays beneath the surface. They’re also available as a handsome slipcased set.

Boxers, the more substantial of the two volumes (336 pages), records the radicalisation of Little Bao, an imaginative boy in a remote village who becomes embroiled in the bloody campaign against brutal and exploitative foreign interlopers in China, as well as the ‘secondary devils’ – native Chinese who converted to Christianity.

Saints (176 pages) tells the story of one of those ‘secondary devils’ – the put-upon and ill-fated (even from a numerological point of view) Four-Girl, whose motivations for joining the church – initially, at least – are altogether more pragmatic than spiritual. However, as the blood-dimmed tide rises around her, she must decide on her commitment to her new-found faith.

While the books both start off in a very naturalistic mode, driven by the apparent simplicity of Luen’s cartooning style and the carefully measured colour palette of Lark Pien, they soon take a surprising sidestep into magic realism.

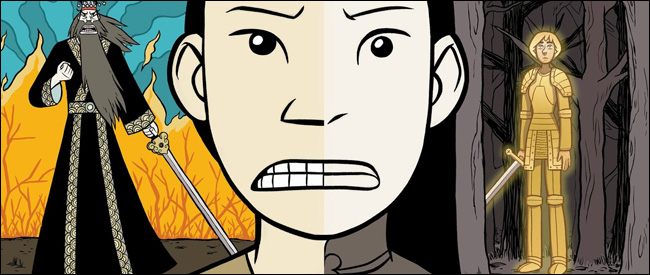

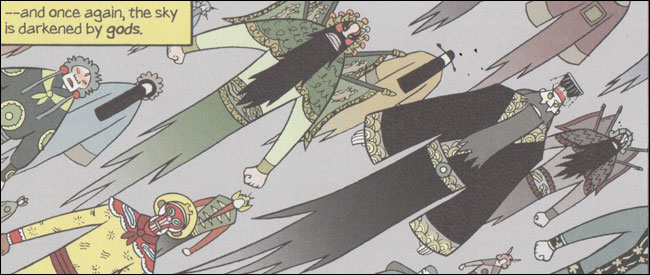

Finding himself mentored by a mountaintop mystic, Master Fat Belly, Little Bao leans to master the power of chi. Before long, he and his comrades can transform themselves into the colourful avatars of ‘gods’, nudging the story – unexpectedly – closer to a dark superhero tale.

Meanwhile, Four-Girl – or ‘Vibiana’, as she is baptised, named after a canonised martyr whose relics have ended up enshrined in Los Angeles Cathedral – finds herself visited by an apparition of a golden young woman who becomes a warrior. It soon becomes clear to the reader – and the historically aware adults around Four-Girl – that she’s having visions of Joan of Arc (and her struggle to clear France of the English).

The difficult trick that Yang manages to pull off beautifully in Boxers and Saints is to power an entertaining story with these fantasy elements while never losing sight of the horrible reality of the rebellion. While it’s easy to sympathise with the Boxers’ desire to liberate their land from foreign influence (and to draw correspondences with Joan’s ‘holy’ mission), the savagery of their carnage delivers gut-punch after gut-punch to the reader.

In one particularly chilling scene, Bao and his rebels barricade Christian women and children into a church and set fire to it. All the while, the reticent Bao insists on one of his comrades reeling off the fanciful litany of unnatural crimes attributed to the foreign and secondary ‘devils’, in order to justify his atrocity. Bao knows Lu Pai’s stories are ‘filled with outlandish lies’, but this abdication of responsibility makes the massacre even worse.

Saints might be a ‘quieter’ book, lacking some of the brutal drama of Boxers, but as it approaches its conclusion, we are sharply reminded of the terrible fate that awaited the noble Joan – and given a jolting foreshadowing that something similar might await Four-Girl/Vibiana.

Luen manages to handle disturbing ideas with a deceptively light touch – particularly the dangers of fanaticism and fundamentalism. In its rigid adherence to its ‘edicts’, the nationalist Big Sword Society is proud that it “erases doubt and establishes laws so we all will know what to shun”.

However, the harsh realities of the rebellion also brush against such contemporary concerns as misogyny (some of Bao’s comrades believe they can be ‘polluted’ by female yin energy), the plight of refugees and even the medicinal use of illicit drugs.

His clear-lined, sometimes even slightly awkward style has incredible impact, depicting unblinkingly the barbarism of which humans are capable. He doesn’t hit you over the head with the horror of what you’re seeing, as a more expressionistic artist might, but just depicts the events in as neutral a manner as possible and invites you to provide your own response.

The author’s aim was that the books could be read in either order, but I think it’s fair to say you’ll get a more satisfying emotional wallop if you come to Saints second. The final pages of the main story are as devastating as just about any comic I’ve read in 30 years, filling in a scene that merely slips between two frames in Boxers. Then, in an epilogue, we’re allowed at least a glimmer of hope.

As a pair of books primarily targeted at young adults and given Yang’s deceptive style, Boxers and Saints provided me with much more than I expected – a rich blend of the political, personal and historical, delivered in an accessible but enormously powerful style.

As a pair of books primarily targeted at young adults and given Yang’s deceptive style, Boxers and Saints provided me with much more than I expected – a rich blend of the political, personal and historical, delivered in an accessible but enormously powerful style.

This is a major work that should be read outside the bubble-universe of comics – and hopefully literary recognition such as the National Book Awards (Yang was a finalist once again this year) will bring the books to the audience they deserve.

Gene Luen Yang (W/A), Lark Pien (C) • First Second, Boxers $18.99, Saints $15.99, Box Set $34.99, September 2013