At a time when millions worldwide are taking to the streets in protest of systemic racism, the stripping of women’s rights, and the division between people and their elected officials, books like Six Days in Cincinnati are more necessary than ever. Through a potent blend of comics journalism, personal memoir, and activist outreach, Dan Mẽndez Moore resurfaces a critically ignored moment in recent American history and brings the comics medium back to its roots as a uniquely popular artform.

At a time when millions worldwide are taking to the streets in protest of systemic racism, the stripping of women’s rights, and the division between people and their elected officials, books like Six Days in Cincinnati are more necessary than ever. Through a potent blend of comics journalism, personal memoir, and activist outreach, Dan Mẽndez Moore resurfaces a critically ignored moment in recent American history and brings the comics medium back to its roots as a uniquely popular artform.

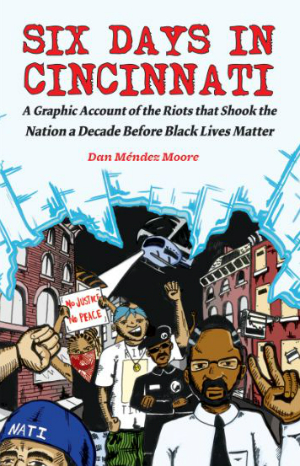

Six Days in Cincinnati (ponderously subtitled as “A Graphic Account of the Riots That Shook the Nation a Decade Before Black Lives Matter”) has had a circuitous, but illuminating, path to its current publication. Before Moore was a chronicler of this story, he was a high school activist and founder of the Cincinnati Radical Youth who played an active role in events the book covers: the six days of protests following the police killing of Timothy Thomas, a 19-year-old unarmed Black man, in the working-class neighborhood of Over-The-Rhine. He then started drawing a comics account of his own experiences as well as his interviews with other participants.

(ponderously subtitled as “A Graphic Account of the Riots That Shook the Nation a Decade Before Black Lives Matter”) has had a circuitous, but illuminating, path to its current publication. Before Moore was a chronicler of this story, he was a high school activist and founder of the Cincinnati Radical Youth who played an active role in events the book covers: the six days of protests following the police killing of Timothy Thomas, a 19-year-old unarmed Black man, in the working-class neighborhood of Over-The-Rhine. He then started drawing a comics account of his own experiences as well as his interviews with other participants.

Microcosm Publishing originally published the book, a fiery, raw account that sings with the energy of the events it recounts, in 2012 under the title Mark Twain Was Right – a reference to Twain’s quote that he wants to be in Cincinnati at the end of the world because “everything comes there 10 years later.” When the streets first broke out into civil unrest in 2001, the most obvious cultural touchpoint were the Los Angeles riots following Rodney King’s slaying a decade before. Today, Thomas’s killing brings to mind the 963 people shot and killed by police in 2016 and the heavy new significance of city names like Ferguson, Baton Rouge, Charlotte, and so many more. Perhaps in recognition of this new reality, Microcosm is preparing a new release of the book in May under its new title.

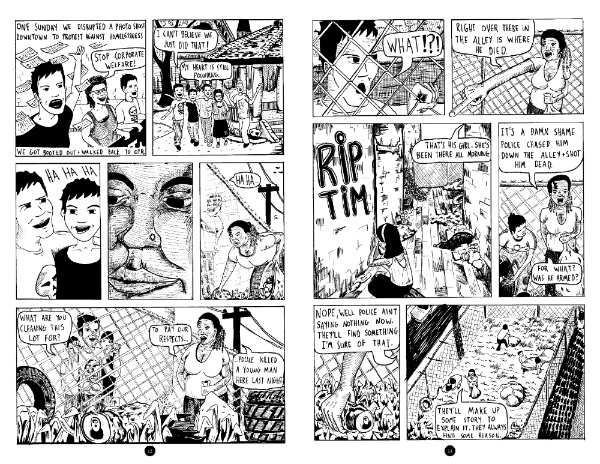

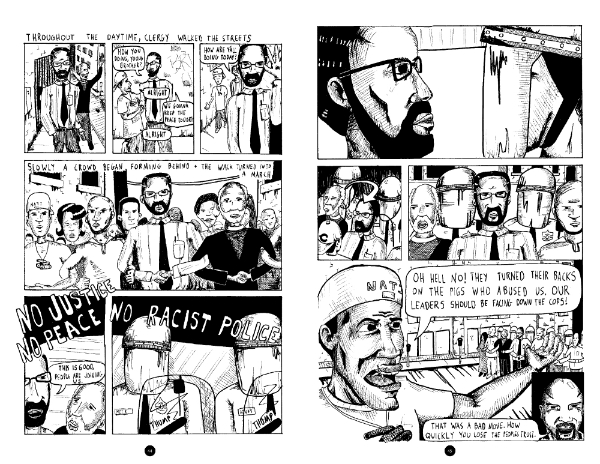

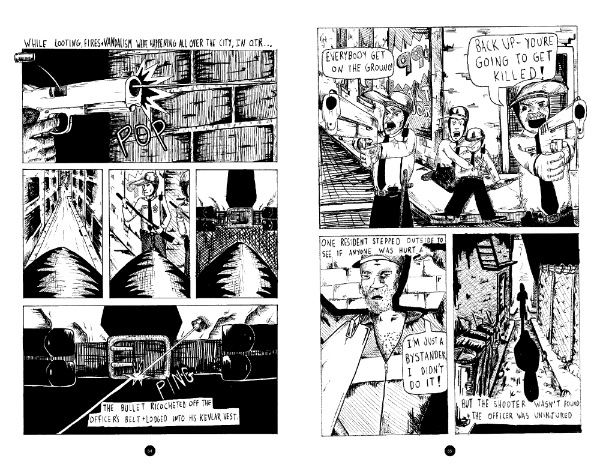

What hasn’t changed in the last five years, however, is the book’s critical perspective on the varying social and state forces at play in Cincinnati and their effects, including the fraught path to justice for Thomas’ mother and the Over-The-Rhine community as well as the random acts of violence that broke out on the fringes of the movement. Outsiders attack drivers and commandeer their vehicles. An officer is shot (the bullet hits his belt).

In one memorable sequence, Moore illustrates an interview with an individual known only as “Frost” who admits, “I ain’t gonna lie, I did some looting.” Frost is neither ignorant of nor apologetic for the effects of his actions on the protester’s overall goals. It’s a testament to Moore’s skills as an interviewer, though, that he both draws out and recognizes the moments within his sources’ stories that speak for themselves. “No, but that might work,” Frost responds in a flashback when one of his friends questions the connection between looting and the fight for justice. “We could make a statement. They’d hear us then.”

Readers accustomed to the technical craft of Joe Sacco or Sarah Glidden might be put off by the unpolished look of Moore’s pages, which often look like they’ve been hastily scribbled out and sent off to the photocopier without a second glance. Then again, though, this is part of the book’s unique appeal. Moore’s rough technique captures the individuality and the passion of the riots themselves as well as any professional photos from January’s Women’s Marches around the world.

Moore has also structured the book in such a way that shows an impressive amount of forethought. The main action of the book is divided into six sections corresponding to the days of the riots. Each one opens with the same motif: a nine-panel grid depicting the events leading up to Thomas’s death. Initially, only the final panel of Thomas lying dead in a non-descript alley is visible with the rest blacked out like empty windows (recalling the unnatural lull that falls over the city when Mayor Charles Luken issues a citywide curfew to curtail the protests). It’s the most effective way possible of conveying the fog of misinformation that initially surrounds this pivotal event, and each new day brings further insights into Thomas’s death and life.

Given the book’s scope, some topics are bound to get less play. The City’s ultimate concessions to the calls for justice – including the first tentative steps toward an alliance between community organizers and elected officials – are packed into a few text-heavy pages near the end. Moore’s personal involvement also takes a backseat in the latter half of the book as events take on more national significance, but it’s nevertheless easy to see why this fraught week remains such an enduring and formative period in his own political and artistic development.

In an epilogue, he shares stories from friends recalling their own experiences a decade removed. On the surface, the book ends as it began – as a story about individual human beings and how we choose to act when faced with seemingly insurmountable forces. But in today’s climate, the undercurrent of this final scene can’t be ignored: the importance of fostering communication and solidarity in the hopes of not making the same mistakes again. It’s a lesson that always bears repeating for those who envision a better world, and Six Days in Cincinnati is a vital and hot-blooded refresher.

Dan Mẽndez Moore (W/A) • Microcosm Publishing, $11.95 • May 6, 2017

[…] Check out an interview with creator Dan Mendez Moore over at Literary Hub, or check out some of the other love on Library Journal or Broken Frontier. […]