A celebration of the sprawling possibilities of comics as a form? A dissection of the fundamental nature of a creator’s relationship with their audience? Or a slice-of-life drama about growing up and moving on? Karrie Fransman’s Death of the Artist is actually all of these things. It’s a graphic novel that reveals new thematic layers on every revisit, daring its readership to consider their connections to text and characters while ceaselessly reminding them of the expansive potential of sequential art as a unique storytelling medium.

The surface premise of Death of the Artist is an elegantly simple one. Five former university friends – Fransman herself, photographer Helena Harvey-Pollena, graphic designer Jackson Harvey, poet and painter Manuel Rangan, and zine-maker Vincent Abiss – embark on a creative reunion ten years after their studies ended, and spend a supposedly carefree week in a remote cottage in the Peak District. There they have resolved to try and reclaim their artistic spirits by each contributing a story to a group project on the theme of the ‘Death of the Artist’. It’s a defiant attempt to recapture the past as they enter their thirties and remember the people/creative forces they used to be. But as the week proceeds events come to a darker turn and their area of artistic investigation takes a very literal subsequent twist…

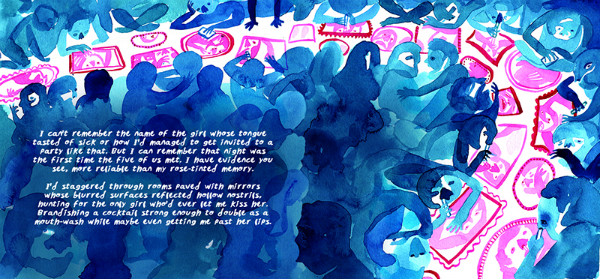

Death of the Artist is a difficult book to review from the perspective of playing along with its core narrative conceit so I’ll remark from the outset that it’s a graphic novel credited to “Karrie Fransman and friends” and – as much as I can – leave the exercise of reading between the lines to those perusing this piece. Each chapter of the book is told through the medium of choice of the five friends and embodies the quirks and tics of their individual personalities, combining to tell one full story from a number of differing standpoints. Manuel’s first entry (above), for example, looks back on how the group first met at a uni party and is told in a curious mix of poetic language and storybook visuals. A juxtaposition of the childlike and the sophisticated that reflects Manuel’s duality as he selfishly seeks respite from his adult responsibilities.

Death of the Artist is a difficult book to review from the perspective of playing along with its core narrative conceit so I’ll remark from the outset that it’s a graphic novel credited to “Karrie Fransman and friends” and – as much as I can – leave the exercise of reading between the lines to those perusing this piece. Each chapter of the book is told through the medium of choice of the five friends and embodies the quirks and tics of their individual personalities, combining to tell one full story from a number of differing standpoints. Manuel’s first entry (above), for example, looks back on how the group first met at a uni party and is told in a curious mix of poetic language and storybook visuals. A juxtaposition of the childlike and the sophisticated that reflects Manuel’s duality as he selfishly seeks respite from his adult responsibilities.

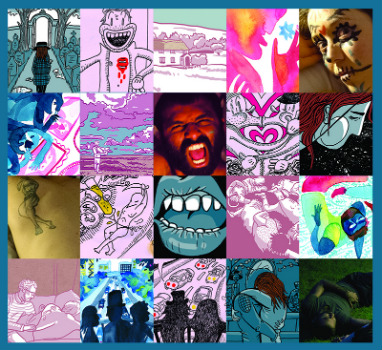

All of these single offerings from the quintet give visual commentary in the same vein into both their perceptions of self and their insights into each other. If Manuel’s tale is one of hazy remembrance then the clarity of Jackson’s linework and restrained use of colour places it in the stark actuality of the present day, as he recounts in diary comic style how the five meet and settle in to the cottage. Helena provides a photographic account of the group’s last fateful night in the cottage that again fuses disparate presentational techniques as she drapes a fairy tale veil over dissolute reality (above).

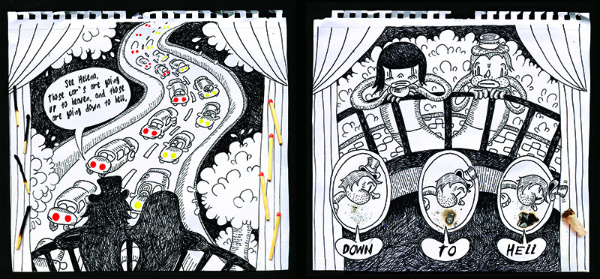

Shifting tone again, Vincent’s troubled, self-destructive life is presented in the style of the classic age of 1930s animation (below), emphasising the manner in which his unsettled past has led to him hiding behind a mask of exaggerated anecdotal braggadocio, fuelled by illicit stimulation from other sources. It’s only when we get to the final chapter – an aftermath that acts as both coda and prelude to the ideas of death and rebirth examined throughout the book – and the contribution of Fransman’s own on-page persona, that the reader finds themselves experiencing anything approaching the usual visual sensibilities of a Karrie Fransman comic.

It was not without reason that when Over Under Sideways Down – the comic Fransman worked on for the Red Cross Refugee Week last year – won the Broken Frontier 2014 Best One-Shot Comic Award that I said “there are few creators working in British comics at the moment with such a powerful understanding of the unique potential of the form as Karrie Fransman.” You can always be guaranteed that her work will display not just a commitment to exploring everything that comics can be but also to take on an almost evangelical stance on the breathtaking opportunities inherent in its storytelling structures. So it is here within the pages of Death of the Artist – a book that represents an awe-inspiring reminder of the complexities, the inventiveness, the eloquence and the articulacy of the language of comics.

It was not without reason that when Over Under Sideways Down – the comic Fransman worked on for the Red Cross Refugee Week last year – won the Broken Frontier 2014 Best One-Shot Comic Award that I said “there are few creators working in British comics at the moment with such a powerful understanding of the unique potential of the form as Karrie Fransman.” You can always be guaranteed that her work will display not just a commitment to exploring everything that comics can be but also to take on an almost evangelical stance on the breathtaking opportunities inherent in its storytelling structures. So it is here within the pages of Death of the Artist – a book that represents an awe-inspiring reminder of the complexities, the inventiveness, the eloquence and the articulacy of the language of comics.

It’s that deft manipulation of the visual cues that make up the comics-reading experience that makes each story so resonant in its communication of the hopes and vulnerabilities of this cast of characters. Levels of actuality are intertwined with subjective perceptions of events to create a world where objective truth is obscured and the reader must work to extract their own semblance of veracity from these sometimes inconsistent yet often overlapping sources. Each player is forced to confront the death of their ambitions in a meditation on how the life we pragmatically accept overwrites the dream of the one we envisioned for ourselves.

It’s that deft manipulation of the visual cues that make up the comics-reading experience that makes each story so resonant in its communication of the hopes and vulnerabilities of this cast of characters. Levels of actuality are intertwined with subjective perceptions of events to create a world where objective truth is obscured and the reader must work to extract their own semblance of veracity from these sometimes inconsistent yet often overlapping sources. Each player is forced to confront the death of their ambitions in a meditation on how the life we pragmatically accept overwrites the dream of the one we envisioned for ourselves.

It’s intriguing that Death of the Artist manages to achieve a connection between audience and characters that is based on a foundation of recognition and shared experience but not, perhaps, one of empathy. In fact there’s a feeling of detachment from the five protagonists throughout – an air of observing their existences rather than living them – that is only exacerbated by some of the pivotal dramatic moments of the graphic novel. As readers we probably identify with their irresponsibility, self-absorption and narcissism far more than we would want to admit to out loud.

Of course, there’s one other strata of meaning that could be applied to Death of the Artist. By her teasing use of ambiguous on-page avatars Fransman has to a degree separated herself from the bulk of the work, subsuming herself in the personas of the cast and creating a very different relationship between reader and narrative. The death of creative ego, perhaps? And the birth of a purer reading experience where the audience is one step removed from obvious authorial intent and encouraged to discover their own personal significance from the book’s themes and motifs?

Of course, there’s one other strata of meaning that could be applied to Death of the Artist. By her teasing use of ambiguous on-page avatars Fransman has to a degree separated herself from the bulk of the work, subsuming herself in the personas of the cast and creating a very different relationship between reader and narrative. The death of creative ego, perhaps? And the birth of a purer reading experience where the audience is one step removed from obvious authorial intent and encouraged to discover their own personal significance from the book’s themes and motifs?

In many ways it’s the deliberately indefinable nature of Death of the Artist that is its greatest strength. In the same way that the aspirations of its characters slip elusively from their grasp so are we, as the audience, reminded subtly and yet brutally through their stories of the intangibility of our own dreams. Death of the Artist is more challenging in many ways than anything Fransman has produced before and, I suspect, more divisive than any of her work to date. Nevertheless it is also very probably her greatest achievement yet as one of UK comics’ most dexterous exponents of the singular narrative opportunities of the form.

Karrie Fransman and friends (W/A), Jonathan Cape, £14.99, March 2015