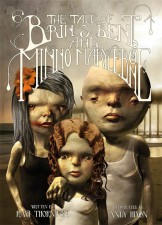

In 2012 cross-media creator Ravi Thornton made an immediate impact on the world of comics with the dark and layered fantasy The Tale of Brin & Bent and Minno Marylebone, published by Jonathan Cape. Written by Thornton, and illustrated by Andy Hixon, that allegorical offering was voted Broken Frontier’s Best Debut Graphic Novel in our 2012 annual BF Awards.

In 2012 cross-media creator Ravi Thornton made an immediate impact on the world of comics with the dark and layered fantasy The Tale of Brin & Bent and Minno Marylebone, published by Jonathan Cape. Written by Thornton, and illustrated by Andy Hixon, that allegorical offering was voted Broken Frontier’s Best Debut Graphic Novel in our 2012 annual BF Awards.

Thornton’s work combines performance with the printed page, allowing her narratives to embrace the diverse storytelling potential inherent in different media. Last month I reviewed her latest graphic novel HOAX Psychosis Blues here – one strand of her current HOAX project alongside the musical HOAX My Lonely Heart, opening tonight at Manchester’s Royal Exchange Theatre.

HOAX Psychosis Blues has its origins in one of a number of poems written by her brother Rob (often in collaboration with Thornton) whose posthumous body of work detailing his life in the grip of schizophrenia is both the foundation the book is built on and the emotional territory it explores. With contributions by comics talents like Bryan Talbot, Hannah Berry, Rian Hughes, Karrie Fransman and Mark Stafford it acts as both a standalone entity in its own right and a companion piece to the stage show.

Broken Frontier caught up with Ravi to talk about both strands of HOAX, reactions to Brin & Bent two years on, the power of the graphic memoir, and the cross-media creative experience…

BROKEN FRONTIER: For those who may be discovering your work for the first time through this interview could you give us a little background on Ravi Thornton and your journey into comics to date?

RAVI THORNTON: Actually, I can’t profess to being a long-time comics fan or aficionado of any kind. My real love was always illustrated prose – the work of Charles Vess, Arthur Rackham, Aubrey Beardsley, for example. Then one day I saw my brother’s copy of Slaine The Horned God Volume 1. I was really moved by Simon Bisley’s artwork, and I guess that changed my perception of comics quite profoundly. Not long afterwards, my brother gave me a copy of Audrey Niffeneger’s The Three Incestuous Sisters, and that reaffirmed my growing suspicion that there was much more to the medium of comics than I had thought.

Since then I’ve realised the great breadth and depth of comics and comics arts styles, and gained huge respect for and enjoyment from them. Most of all I love it when it when the two (sequential art and illustrated prose) cross over, and I suppose that’s why I create my graphic novels in the way that I do.

Since then I’ve realised the great breadth and depth of comics and comics arts styles, and gained huge respect for and enjoyment from them. Most of all I love it when it when the two (sequential art and illustrated prose) cross over, and I suppose that’s why I create my graphic novels in the way that I do.

About my background? Well I’ve been writing prose for several years, and have always been a highly visual writer, but it was the Niffeneger moment that made me think about storytelling with images as well as words. I had the basis of a text that I thought would work well in this way, called The Tale of Brin & Bent and Minno Marylebone. However, not being an illustrator myself meant bringing in a collaborator, which in turn meant writing a script for them to follow. I tried it. It worked. And I’ve been writing cross-media scripts ever since.

BF: We spoke in some depth a couple of years ago at Broken Frontier about Brin & Bent and that cross-media collaborative process with illustrator Andy Hixon and composer Othon who provided the graphic novel’s soundtrack. Given the challenging nature of its narrative, which aspects of both the reactions to the book and the audience’s perceptions of it have most intrigued you?

THORNTON: I think I was most intrigued at how literally the book was read given its very surreal appearance. Perhaps that’s a naïve thing for to say, because the use of a child as metaphor for vulnerability was always going to be controversial in the sexual context of this tale. I just never thought of it that way when I was writing it.

Of course I had to think about that when Cape’s printers refused to print the book on the grounds of it not only promoting but condoning paedophilia; hence the addition of the foreword revealing that the origins of the story were autobiographical. But in some ways the response to that only intrigued me more. I guess the assumption was that I was a victim of child abuse (whereas actually the book is about a rape I suffered as an adult); yet instead of eliciting a supportive response, that assumption only seemed to disturb the audience more. Perhaps this says something about how we deal with victims of child abuse as a society?

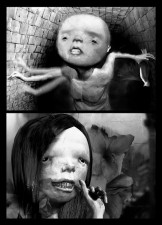

The cover and images from The Tale of Brin & Bent and Minno Marylebone, published by Jonathan Cape

It was only after I went public with the actual origins of the story, that the response to the book became much more sympathetic. I even tested the theory when the US edition came out, by making the foreword more explicit (‘I was twenty-one: he was brutal.’). Sure enough, where previous reviews had been dominated by such words as ‘disturbing’, ‘bizarre’, ‘fucked up’, now we had ‘wrenching’, ‘cathartic’ and most interestingly ‘heart’ instead.

The critical response to Brin & Bent has been amazing. It’s been nominated for and won awards. It’s even being taught, complete with soundtrack, on the second year English Literature syllablus at The University of Nottingham. And it’s very gratifying to hear that, now that the origins of the story are clear, the book is helping to empower a number of its readers. But I think it’s the audiences perceptions of, and reactions to, the storytelling anchors – or lack of storytelling anchors – that has really intrigued me the most.

BF: I think that’s actually a very interesting point in that it opens up questions about the complexities of the author/audience relationship. Although it was obvious when I first read Brin & Bent that there was a dark truth at its core it still felt that I was also being invited to find my own meaning from the imagery and symbolism of the book, and that was a vital part of the experience. In what circumstances do you feel a narrative with an oblique or representational style works most effectively to convey your message and when is a more direct storytelling approach appropriate to the themes of the material?

THORNTON: I’m not sure I have a rule on themes, as such. I guess it’s a more intuitive process than that. Or rather, I just seem to follow what the story demands.

Having said that, I suppose those demands then conform to my natural writing style, which is quite vivid, but also quietly restrained. So if a story demands a brutal grotesquery, because it was based on such a brutal and grotesque act as rape, then I naturally lean towards conveying that through metaphor, because I’m not really interested in shouting to make my point heard, I’d much rather the audience have to come close.

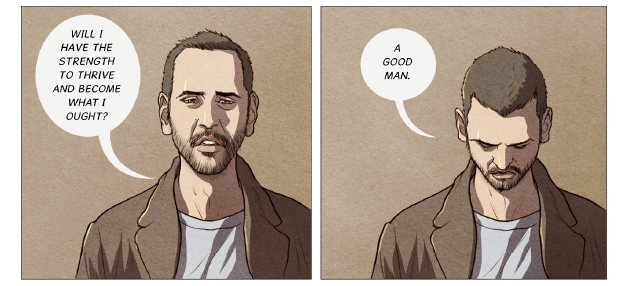

But with HOAX Psychosis Blues, for example, although the condition of schizophrenia is no less monstrous, the story is actually about the man beneath it, which means, as the author, I have to build intimacy; and I find the best way to do that is to be honest and accessible with human emotions. Hence the simple real-world scenes in Psychosis Blues, to give us our empathetic core.

Highly atmospheric artwork from Mark Stafford in HOAX Psychosis Blues

It always comes down to what will best serve the story being told. As a third example, I’ve recently started working on another project that takes the common occurrence of a break up but sets it within a geological and mythological vastness. Why? Because the story is one of questions and searching, which is the story of all break ups everywhere, the world over. In this case the idea is not to present an immediate intimacy, but allow the audience to find that intimacy as they journey through the story by ultimately arriving at this universal human truth.

Hmm. Reading this back, maybe I do have rules!

BF: HOAX Psychosis Blues and HOAX My Lonely Heart are the two main strands of your current cross-media project. I reviewed HOAX Psychosis Blues here at Broken Frontier recently but could you give us the background to HOAX in your own words and what you’re hoping to achieve with your Ziggy’s Wish publishing endeavour?

THORNTON: HOAX tells the story of my brother, Rob, who committed suicide in 2008 aged 31 after a long battle with schizophrenia. The musical HOAX My Lonely Heart unfolds a painful love story in the six months pre Rob’s diagnosis as schizophrenic, whilst the graphic novel HOAX Psychosis Blues charts his life over the nine years post diagnosis through to his death. Both pieces stem from a single one of my brother’s poems titled ‘HOAX’.

The manifestations of Rob’s illness were at once so immediate and yet so distant that I was looking for a way to explore both of these extremes. I chose stage, because of its intensity, as the medium to explore the former; and sequential art, which can revisited time and again, and explored as lightly or as a deeply as the audience wishes, as the medium to explore the latter.

These choices were made very carefully. Although this story is about a man and his humanity, it is set within the context of mental health: a very sensitive subject that people need to be able to enter into at an emotional volume to suit themselves. Thus the musical slams the issue on the table, whilst the graphic novel presents the space around the table in which to reflect. Combined, this presents a very powerful experience – though the two parts also work as standalone pieces.

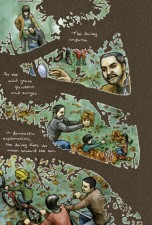

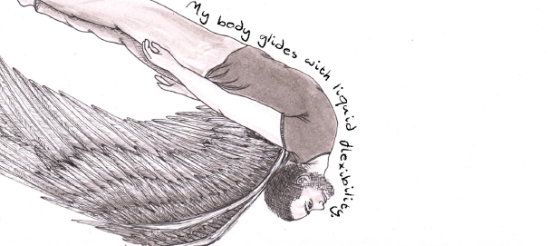

Interior pages with visualisations of Rob’s poetry from Rhiana Jade, Hannah Berry and Julian Hanshaw

I set up Ziggy’s Wish so that I could raise money for charity through my storytelling – something that’s difficult to do when your work goes through mainstream publishers. I’m not looking to become a global powerhouse, just to create and sell special limited editions of certain stories so that I can give a decent percentage of profits made from those stories to charities that relate to them in some way. With HOAX Psychosis Blues, it is mental health charities that Ziggy’s Wish will support. Other projects will support different charities, like upcoming Scamp and Zoom, for example, which is a picture-book about a greyhound, and will support animal charities with its sales.

BF: Returning to that sense of intimacy between creator and audience again for a moment, the artists you chose to interpret Rob’s poems seem to have been very carefully curated to match subject matter with illustrative style. Did you have creators in mind from the outset as appropriate fits for the individual themes of each featured piece of Rob’s work? How aware of the overarching narrative structure of the book were the collaborators in terms of what they were all working on?

THORNTON: I had an idea of some of the creators I wanted to work with (variable 1), and also an idea of the storyline and its structure (variable 2). I then started the process of shortlisting from the several hundreds of my brother’s poems (variable 3), to find those that would firstly support the storyline, and secondly suit the creators’ individual styles. It was a long process, and I had to make changes to all three variables along the way in order to finally end up with my perfect storytelling matches. Fortunately, all but one of those matches I was able to implement, largely due to the good graces of the creators involved! And the one match I had to change, due to the creator being unable to deliver, was only made better by the new creator who took their place.

Powerful HOAX imagery from Karrie Fransman

I actually wrote the graphic novel script as if it were ten separate scripts – with each one of these written specifically for the creator it was going to, in terms of the language and tone I used, and how much direction I included. Apart from Leonardo M. Giron, who illustrated all of the year sections that link the poems into a whole, each illustrator was given script for their poem only, plus the section of Leonardo’s script that immediately preceded it. It was important to me that the creators worked in isolation from one another, because the poems they were illustrating were written in isolation, and from a very isolated, and isolating, mental place. So in fact, apart from Leonardo, the collaborators were completely unaware of the overarching narrative of the book. Most of them are still unaware, having chosen to wait until the physical book comes out next month before they read it.

BF: In many ways the artistic linchpin of the whole exercise is that subtle and visually eloquent framing sequence from Leonardo M. Giron. How did you discover Leonardo’s work and what made him such a good fit for those segments of the book?

THORNTON: I was introduced to Leonardo, or Glen as we call him, by writer and designer Rich James Johnson. I’d been talking to Rich about a possible collaboration, but time was against us so he pointed me in Glen’s direction instead. I loved Glen’s work, and sent him a short-story script that I’d written called Day Release. Like HOAX, the short-story was inspired by my brother’s poetry. It was around the time I was planning HOAX in my head, so there was probably quite a bit of subconscious water-testing going on too….

From his portfolio, I knew my work would be something very different for Glen to tackle: not only because the subject matter was all very ‘ordinary’ (not the sci-fi or fantasy that Glen is renowned for), but also because it was so British, and northern British at that (Glen is Filipino, based in Manila). But the way Glen responded to the script and my directions was just amazing. It’s difficult, when you work with so many amazing talents, to identify what really marks out the best of the best – but Glen would have to be right up there.

The subtle storytelling of Leonardo M. Giron is the book’s artistic linchpin

There’s something so incredibly intuitive in his work, a very sensitive understanding of what it is to be an ordinary human person – which in itself, I think, allows that ordinary human person to become extraordinary on the page. When it came to HOAX some months after that, Glen was top of my list. I knew that once he was on board for the interlinking narrative sections, we would have the strongest possible structure in place upon which to build the rest of the piece.

BF: The combination of artists is fascinating in that it includes legends of the British industry like Bryan Talbot and Rian Hughes, some of the established rising stars of the new wave of UK graphic novelists including Karrie Fransman and Hannah Berry, and relatively unknown creators like Rozi Hathaway (who I’m sure we will be seeing a lot more from in the future!). Was that mix a conscious one or a happy coincidence?

THORNTON: I guess a little bit of both. I knew I needed a certain degree of illustrator clout to help carry a project of this size and scope, particularly in terms of funding and partner support, so when both Bryan and Rian agreed to contribute I was thrilled. Then there were creators, like Hannah, Karrie, Julian [Hanshaw], Mark [Stafford]… who I knew through Cape or their events, knew I wanted to work with, and knew they’d be a good match for the certain sections I had in mind.

An impressive debut from Rozi Hathaway in HOAX Psychosis Blues

And then there were the ‘relative unknowns’. In fact Rhiana [Jade] and Ian [Jones] were already know to me as artists in their own right, and I was keen to champion their work. Rozi was the real wild card. I didn’t know anything about Rozi at all. What I did know was that I wanted to find someone at that level and give them a hand up, because it’s just so tough to get a break in this line of work. I also knew the section that I wanted this particular person, when I found them, to illustrate – a pretty difficult section actually, in more ways than one.

So I set out roaming online portfolios and blogs as I often do when I’m looking for collaborators, and came across one of Rozi’s paintings. I knew as soon as I saw it that there was something in her style that would work for HOAX. I dropped her a line, and she agreed to come on board. It was definitely a challenge for Rozi. She worked long and hard, with more redraws and further directions than all of the other illustrators put together. But it was worth it, and it shows. And I loved working with Rozi precisely because she was willing to work that hard.

BF: You’ve already touched upon the cross-media element of HOAX and how the stage and comics strands complement each other but it would be remiss not to hear from you about the journey that the stage show has taken from genesis to realisation…

THORNTON: Around the same time as I was contemplating my brother’s poetry, and specifically his poem ‘HOAX’, theatre director Benji Reid got in touch, having read my graphic novel The Tale of Brin & Bent and Minno Marylebone. We met and discussed collaboration, and it quickly became apparent we shared an appreciation of finding beauty in the dark. I showed Benji ‘HOAX’. He asked I could develop something from it for stage, so I went away to write HOAX My Lonely Heart….

THORNTON: Around the same time as I was contemplating my brother’s poetry, and specifically his poem ‘HOAX’, theatre director Benji Reid got in touch, having read my graphic novel The Tale of Brin & Bent and Minno Marylebone. We met and discussed collaboration, and it quickly became apparent we shared an appreciation of finding beauty in the dark. I showed Benji ‘HOAX’. He asked I could develop something from it for stage, so I went away to write HOAX My Lonely Heart….

When Benji saw the script, he was as surprised as I was that I’d written a musical, but saw at once how it could work. I then brought musician and composer Minute Taker on board, having heard him play a gig locally in Manchester; whilst Benji sourced our producer Pippa Frith.

Pippa started the ball rolling with funding for our first stage: Research & Development. Arts Council England were our main funders, but we needed more. I’d started work on HOAX Psychosis Blues as an accompanying piece by this time, which meant we already had something quite unusual and exciting in terms of a project, so suggested that we offer it up for academic research. That’s when The University of Nottingham pledged their support, and their English Literature professor Dr Matt Green became our researcher. On the back of this we were able to secure the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester as a partner, and utilise their rehearsal rooms for a week of invaluable ideas testing.

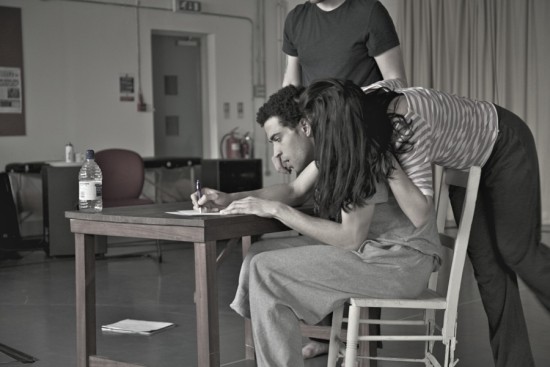

HOAX My Lonely Heart rehearsal photographs above and below courtesy of Benji Reid

All of these things added weight to the project when we went for the second-stage funding that would allow us to premiere the performance and print the graphic novel. The bids we made were successful, then it was full steam ahead to create the musical score for the performance, find and audition the actors, get everyone into the rehearsal room, test the script, make various cuts, marvel at the sheer amount of singing, acting and physical talent in front or us… and make the show.

BF: It’s my firm belief that the rise of the graphic memoir has played a pivotal role in bringing in new readers to the world of graphic novels who were previously unaware of the storytelling potential of the form. Do you have any thoughts of why comics as a medium are so effective in communicating personal experience in such an empathetic way?

THORNTON: I suspect there are several factors at play. In no particular order… One: That our most basic form of understanding, as humans, is that of reading faces. Two: Comics present a multi-faceted landscape which in some ways is more akin to cinema than prose; such that whilst you are following the core strand of the story, you are constantly being fed other information from around that core on the page. This makes for very effective emotional engagement. Three: Comics are immediately accessible because they offer a visual entry level, and then immensely rewarding as the audience discovers further layers in both the visual and the text. Four: It might sound strange, but I feel there is a gentleness to comics, quite apart from the subject matter, which can of course be very violent. There is a dignity, a respect for the skill that has gone into the work of a comic, that reminds the audience of the humanity and the humility behind it. Five: Comics are a very stripped-down form of storytelling, and when you strip things down, you nearly always arrive at the truth.

BF: You may not be thinking too far ahead after the last few months of working so intensively on HOAX but, as a final thought, what can you tell us about what we can expect from Ravi Thornton in the near future?

THORNTON: I’ll be focusing quite a bit on Ziggy’s Wish, tightening things up there, further promoting HOAX Psychosis Blues and getting ready for the next publication, Scamp and Zoom. I’ve also recently started working on a new book with two very interesting illustrators, Alan Dalby and Chris Madden, called The Giant’s Wife. We’re aiming to create something a bit different, something that blurs the line between illustrated prose and comics. And there’s another collaborative cross-media project I’ve been slowly building for a while now, called CIRCUS (working title), that explores whether biochemical triggers can empower victims of abuse. This will involve sequential art, theatre and also gaming, so I’ve quite a bit of writing to do for that.

You can order a copy of HOAX Psychosis Blues here from Ziggy’s Wish priced £15.99. For more on Ravi Thornton and HOAX visit her website here.