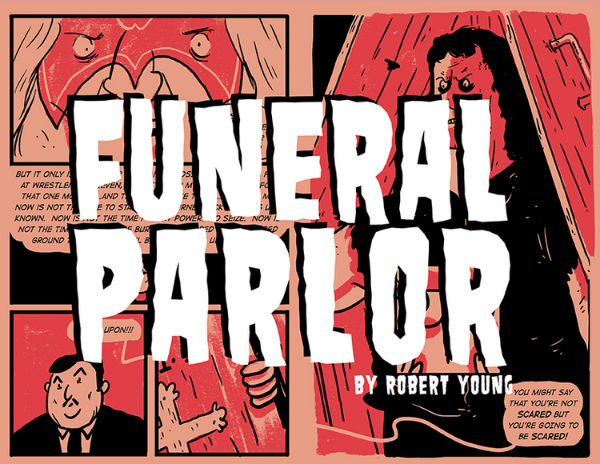

Many autobio comics stylize the events they are depicting to give them flair beyond the original incidents. But what if the events being depicted are already hyper real? Robert Young explores this space in his comic Funeral Parlor, recollecting a series of profound emotions he felt watching WWE programing as a child. Young’s choices in the way he depicts his memory of this event elevate the campy theatrics of professional wrestling to the level of gothic horror. He succeeds in recreating the event not as it was – or even how it exists on video – but how it felt in the moment, and shows the power of professional wrestling to loom as large in our hearts and minds as any epic story.

To set the stage, Funeral Parlor depicts Young as a child watching the portion of the 1991 Undertaker vs. Ultimate Warrior feud in which The Undertaker ambushes Warrior during his manager Paul Bearer’s talk show The Funeral Parlor. Through the eyes of an adult, especially ones familiar with the art of professional wrestling, the whole thing is rather silly even if all the players are performing at the height of their craft. But for a younger viewer such as Young, everything that occurs on screen would appear to be of the utmost gravity.

To set the stage, Funeral Parlor depicts Young as a child watching the portion of the 1991 Undertaker vs. Ultimate Warrior feud in which The Undertaker ambushes Warrior during his manager Paul Bearer’s talk show The Funeral Parlor. Through the eyes of an adult, especially ones familiar with the art of professional wrestling, the whole thing is rather silly even if all the players are performing at the height of their craft. But for a younger viewer such as Young, everything that occurs on screen would appear to be of the utmost gravity.

The Ultimate Warrior is a muscular super man from parts unknown showing his valor in the face of evil. Paul Bearer and The Undertaker are undead demons from the pits of hell luring our hero into a sinister trap. And the plaintive terror in Vince McMahon and Randy “Macho Man” Savage’s voices on commentary once The Undertaker has sealed Ultimate Warrior inside an airtight casket are completely warranted. A line has been crossed even in the highly competitive, testosterone driven world of professional wrestling. A man has seemingly been killed on live television and the world of grown men is revealed to be a deadly one. Because he perceived this episode to be completely real, it ceased to be entertainment and instead became a traumatic event in Young’s childhood.

When replaying this portion of the program on video today the stage lighting and cheap set are readily apparent, but Young makes a wise choice in his art and design choices to conjure the event not as it is recorded but as it appeared to him as a child. Through his cartooning Young is able to remove those goofy moments of Paul Bearer mugging to the camera and hamming it up for those audience members way back in the cheap seats. Here he is depicted as the sunken-eyed, flesh-barely-hanging-on-the-skin ghoul he is meant to be. Ultimate Warrior is a lumbering mountain of a man with action figure proportions.

The caricature on The Undertaker himself is given special care, depicting him not as the green rookie he was at that stage in his career, but instead capturing the aura of unfeeling, unstoppable otherworldly evil he would evoke as a performer decades latter. The ramshackle coffin and candelabras captured on video become black silhouettes against a deep red fog reminiscent of the appearance of the Nazgul in Bakshi’s Lord of the Rings.

The dark clad Undertaker becomes a moving shade. The strongest of panels resembling the shadowy figures cast against the sky in “The Seventh Seal”. The deep blacks and sickly reds of the risograph printing paints a picture not of sweaty costumed men screaming at each other but of a mythological battle of good versus evil. The WWE rarely reaches these heights of storytelling even today, and could only dream of hitting them in the early 90s. When Ultimate Warrior is rescued from the sealed casket, he is carried Christ-‐like from the scene. On video this part of the story is too busy and chaotic to fully capture what Young drives home in a single renaissance painting of a panel. Evil has won this day and good may never recover.

The dark clad Undertaker becomes a moving shade. The strongest of panels resembling the shadowy figures cast against the sky in “The Seventh Seal”. The deep blacks and sickly reds of the risograph printing paints a picture not of sweaty costumed men screaming at each other but of a mythological battle of good versus evil. The WWE rarely reaches these heights of storytelling even today, and could only dream of hitting them in the early 90s. When Ultimate Warrior is rescued from the sealed casket, he is carried Christ-‐like from the scene. On video this part of the story is too busy and chaotic to fully capture what Young drives home in a single renaissance painting of a panel. Evil has won this day and good may never recover.

Young frames this entire story with images of himself as a child watching this all play out on television. As Ultimate Warrior is being rescued Young is reduced to hysterics fearing his hero has died before his very eyes. His mother comes to comfort him while his uncle chides him for fully investing in the show that is professional wrestling. Yet this is the majesty of showmanship, the point where the performers have gotten the audience to wholly suspend their disbelief and go along for the ride. The performers on that night in 1991 were able to do that to Young as a child, and in turn Young is able to do that to us as readers. By turning muscled up vaudeville into an Albrecht Dürer painting Young’s childhood terror is transmitted to us.

We are transported into his childhood bedroom feeling his fear as much as Young was transported to that arena praying that Ultimate Warrior was still breathing. He is able to transcend the trap of a simple nostalgic call back and tap into that deeper moment we all have as children when the story we are being told becomes too scary or too real and we need to be comforted.

Pro wrestling fandom has been intersecting more regularly with indie comics over the last five or six years. And while many comics have captured the kinesthetic motion, the grit, the pageantry, or the pomposity of the art, none have so acutely captured its ability to tap into our subconscious and touch something deep with in. In Funeral Parlor pro wrestling is as real as real can be.

Robert Young (W/A) • Self-published, $10.00

You can buy Funeral Parlor online here priced $10.00.

Review by Robin Enrico