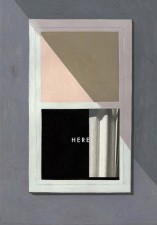

Twenty-five years on from its original publication in Raw, Richard McGuire has expanded his innovative six-pager ‘Here’ into a lavish visual symphony of time and place, eternity and ephemerality.

Back in 1989, the notion of comics being taken seriously as an art form seemed to be a lot more likely than David Hasselhoff using the power of song to bring about the downfall of the Soviet Union.

Back in 1989, the notion of comics being taken seriously as an art form seemed to be a lot more likely than David Hasselhoff using the power of song to bring about the downfall of the Soviet Union.

And if you young whippersnappers don’t believe me, maybe you’ll believe this blurb from the back cover of Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly’s cutting-edge anthology Raw (Vol.2 #1), published that year in the UK by eminent mainstream imprint Penguin.

Alright, the word is out. Now it’s safe for adults to read comics. You don’t automatically lose IQ points.

They’re coming through culture’s front door as “Graphic Novels” or “Pictorial Sequential Narratives”. They’re Commix – a co-mixing of words and pictures. French intellectuals read them. It’s okay, really.

Tucked inside that volume, without any fanfare, was a six-page black-and-white piece called ‘Here’, by New York-based artist and musician Richard McGuire (better known at the time as the bass player for post-punk band Liquid Liquid).

It might not have got a mention on the cover, but what McGuire’s story did was to quietly roll a hand grenade under a lot of our preconceptions about what we thought the medium of comics was capable of.

A few years later, no less a figure than Chris Ware wrote, “What [McGuire] gave every reader with ‘Here’ was an individual and unique way of looking at life… It was life-changing.” Quite a claim.

In ‘Here’, across six pages and 36 dizzying panels, McGuire collapsed time to tell the story of a single location from a single point of view, from 500 billion BC to 2033 AD. Weaving the piece from strands of time, the artist overlaid characters and events in a way that hoisted a flag for comics as a medium of unique and almost infinite possibilities.

I wouldn’t have said that my reaction was quite as clear-eyed as Chris Ware’s, but reading those six pages gently cracked open my still fairly youthful understanding of what comics could do – the way, some years earlier, the ‘Once in a Lifetime’ video had made 12-year-old me think about pop music in a whole new way (perhaps not a totally inappropriate connection, given the NYC links).

I’d seen genre material given a bit of a non-linear gloss in comics before, through Bryan Talbot’s Roeg-esque ‘editing’ of Luther Arkwright and Moore and Gibbons’ depiction of Dr Manhattan’s unique perspective in Watchmen.

I’d seen genre material given a bit of a non-linear gloss in comics before, through Bryan Talbot’s Roeg-esque ‘editing’ of Luther Arkwright and Moore and Gibbons’ depiction of Dr Manhattan’s unique perspective in Watchmen.

However, in ‘Here’ the illusion of time became the defining fabric of the story; McGuire’s achievement was to compress an out-of-reality four-dimensional experience into an accessible series of images across a few pages.

A couple of ice ages and mass extinctions later, it finally seems that some of that promise held by the comics medium might be coming to fruition. But while the influence of ‘Here’ has permeated through the comics generations, the story itself – a prisoner of the preTumblrverse – seemed largely to have passed out of circulation.

However, a quarter of a century on, Richard McGuire has reimagined his masterpiece utterly. From its modest origins, ‘Here’ is now a 320-page full-colour hardback, lavishly produced by Hamish Hamilton, an imprint of…Penguin, of course.

So, in this dramatic transformation, what’s been gained and what’s been lost?

So, in this dramatic transformation, what’s been gained and what’s been lost?

One thing the new presentation reinforces is the theme that’s at the absolute core of ‘Here’: the question of time – and, perhaps more precisely, the doublethink that while our individual lives are virtually insignificant in the unimaginable vastness of geological time, they’re also all we’re going to get, so we’d better make the most of them before they disappear in the blink of a cosmic eye.

Indeed, the timeframe in this new version is more forward-looking than its progenitor, going into a deep future where the presence of dinosaurs gives the sense of a cosmic cycle beginning again (although a present-day television broadcast has reminded the reader that one day the sun will expand to devour the earth, and all this will be gone).

On my first read of the book, I did have a slight sense that the loss of the original’s more intense sense of compression and high-contrast artwork might have drained the work of some of its direct energy. However, once you settle in to the altogether different cadence of the expanded version, the strengths of the new format become increasingly apparent.

On my first read of the book, I did have a slight sense that the loss of the original’s more intense sense of compression and high-contrast artwork might have drained the work of some of its direct energy. However, once you settle in to the altogether different cadence of the expanded version, the strengths of the new format become increasingly apparent.

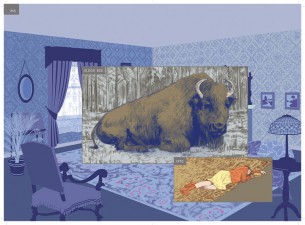

Again reflecting his background, the new scale of the work allows McGuire to play with little recurring threads that are developed like musical themes across the years. For example, at a very basic level, one spread shows wallpaper being removed in 1960, while at the other end of the room it’s being put up in 1949. The format also allows McGuire to explore a wider variety of mediums in the work, from blotchy, textured watercolours to clinical uniform digital fields.

Drawing on McGuire’s own family history (the new version of the book was prompted in part by the death of his parents and the experience of clearing out their house), we see a series of staged family pictures taken in the same place between 1959 and 1979. We see the individuals grow, and are invited to speculate about who these people are and how their characters have developed – tickling the same fascination stimulated by long-form documentary projects like Michael Apted’s 7-Up series.

Other little thematic spreads cover Halloween parties, insults, fights, little girls dancing, mothers and babies, the eternal war between dogs and postmen and the notion of ‘loss’, in all its senses.

Other little thematic spreads cover Halloween parties, insults, fights, little girls dancing, mothers and babies, the eternal war between dogs and postmen and the notion of ‘loss’, in all its senses.

And while we never really manage to get to know or bond deeply with the people who pass through the site, perhaps that’s key to the air of ephemerality that permeates the whole of McGuire’s book. Irrespective of the specific cultural trappings of their age, these people are us (or our ancestors, or our descendents).

It’s great to see a mainstream publisher like Penguin get behind a comic with such a lavish edition, but as handsome as it is, it did leave me with the nagging feeling that it might be slightly overformatted. At £25, is it going to reel in the possibly comics-curious reader who might pick it up off the shelf as an attractive lump of literary fiction?

However, such commercial considerations aside, this is a very welcome addition to the comics canon. To give that musical analogy one last kick, McGuire has managed to pull off the unlikely trick of turning a perfect pop single into an immersive symphony.

Richard McGuire (W/A) • Hamish Hamilton, £25, December 4, 2015. (In the US: Pantheon, $35, December 9, 2014.)

[…] Broken Frontier […]

[…] And there was an exhibition at the Morgan Library relating to the book in 2014. And here’s a good review of the book from the comics blog Broken Frontier. So it must have popped up briefly in my […]