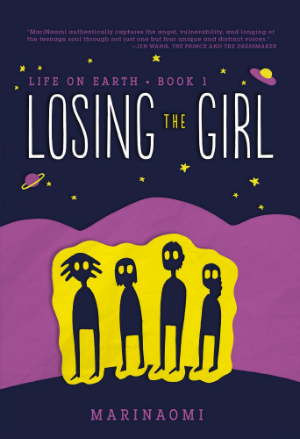

Recently, many indie comics artists have been picking up work for larger publishers in the ever-expanding Young Adult graphic novel market. In Losing the Girl (Life on Earth: Book 1) MariNaomi uses her skills in creating graphic memoir to craft an intricate fictional account of the lives of several high school students over the course of one pivotal summer for said demographic. What makes the book stand out are the sensibilities MariNaomi brings into the work; giving it a subtle, grounded tone while still fully delving into the complex ways friendship and romance can intertwine amidst a small group of people. Even more interesting is that this earthly focus nicely balances an extraterrestrial undercurrent within the margins of the story, suggesting a larger cosmology to be played out over future volumes. The book is smart and nuanced in a way that not only avoids the trap of patronizing its intended audience, but also provides older readers with a way to reflect on the interconnectedness of their own lives.

Recently, many indie comics artists have been picking up work for larger publishers in the ever-expanding Young Adult graphic novel market. In Losing the Girl (Life on Earth: Book 1) MariNaomi uses her skills in creating graphic memoir to craft an intricate fictional account of the lives of several high school students over the course of one pivotal summer for said demographic. What makes the book stand out are the sensibilities MariNaomi brings into the work; giving it a subtle, grounded tone while still fully delving into the complex ways friendship and romance can intertwine amidst a small group of people. Even more interesting is that this earthly focus nicely balances an extraterrestrial undercurrent within the margins of the story, suggesting a larger cosmology to be played out over future volumes. The book is smart and nuanced in a way that not only avoids the trap of patronizing its intended audience, but also provides older readers with a way to reflect on the interconnectedness of their own lives.

The central narrative of Losing the Girl follows the lives of several high school students in the fictional semi-suburban town of Blithedale in what feels to be California. It is through this ground level focus on the lives of her teenage protagonists that MariNaomi produces the drama of Losing the Girl. Each of the chapters details the events of the summer from the perspective of a different teenager within the friend group, primarily in relation to the book’s central character Emily Hiroko Baker. We begin by following surly skateboarder Nigel Jones as he returns from school to his fraught home life. After his divorced mother interrogates him about school and his father, Nigel retreats to the silence of his room. At school however he is jovial if rather corny in his courtship of Emily. The pair hit it off romantically though Nigel is constantly stepping on his own feet with Emily, especially when it comes to asking if she will lose her virginity to him. Wanting to lose it to someone she deems more worthy Emily dumps Nigel, setting in motion the major arc of the plot.

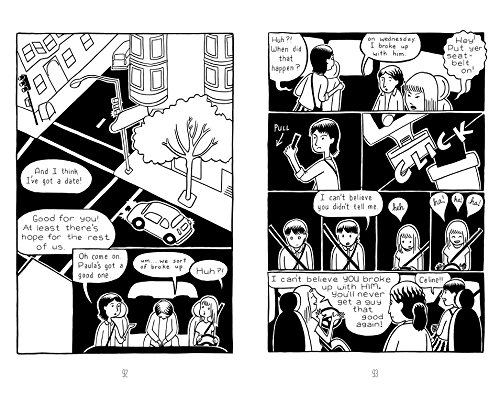

Emily’s story then comprises the second chapter as well as the bulk of the narrative. We follow Emily, Celine, and Paula to a party where she sets up a date with the true object of her affections Brett Hathaway. The pair go on a few fumbling dates, all while tensions between Emily and the spurned Nigel escalate. Emily loses her virginity to Brett but realizes soon after that she is pregnant. After her family finds out, she goes through with having the abortion. Sadly in this trying time her friends prove to be useless in comforting her, particularly Nigel and Brett though neither know the truth about what she is going through.

It is a bold decision to make Emily’s experience the central one in the narrative. MariNaomi doesn’t sensationalize what she is going through, nor push it into melodrama. The focus rarely strays from Emily as things unravel for her, and while we do not see her undergo the procedure, we follow her conflicted tortured thoughts leading up to and following her abortion. Given access to Emily’s thoughts here makes the inefficacy of her friends doubly painful, but it reinforces how ill-equipped they are to deal with an issue of this magnitude.

It is a bold decision to make Emily’s experience the central one in the narrative. MariNaomi doesn’t sensationalize what she is going through, nor push it into melodrama. The focus rarely strays from Emily as things unravel for her, and while we do not see her undergo the procedure, we follow her conflicted tortured thoughts leading up to and following her abortion. Given access to Emily’s thoughts here makes the inefficacy of her friends doubly painful, but it reinforces how ill-equipped they are to deal with an issue of this magnitude.

This inability of the teens to cope with Emily’s suffering is further reinforced in the chapters focusing on Brett and Paula. Despite his relationship with Emily, Brett secretly paints pictures of his true love Johanna. When the two discuss their futures away from Blithedale looking out at a lake, it is Johanna who reveals that Emily had an abortion to him. Though Brett tries to talk things out with Emily, he is unable to give her the support she needs. Meanwhile, her best friend Paula struggles with her with her violent ex-boyfriend Darren as well as her jealousy of what she views as Emily’s charmed life. It is this jealousy that leads her to kiss Brett behind Emily’s back. An act that she feels is so unforgivable that she severs her friendship with Emily rather than tell her. Only Nigel is finally able to come to Emily’s aid when he reconciles with her by agreeing to be her platonic pal and leave romance behind.

It is rather surprising to see all of this interwoven Altman-esque character drama about the way romantic desires can fracture and upset our lives within a Young Adult graphic novel. It is to MariNaomi’s credit that she is also able to weave the more genre standard science fiction elements into the background of this otherwise maturely grounded story via two unexplained phenomena. The first being that all cell phones have ceased to function. We are never given a sense of the scope of this problem, only that it persists from the start of the story at the end of May to the end of the story in the middle of August. Emily’s text to Nigel at the end emphasizing that something has shifted not only in their friendship, but also in the cosmology of the story.

While the phone issue is left mostly to simmer in the background of the action, the phenomena of the mysterious disappearance of local girl Claudia Jones is peppered into the characters conversations as well as diegetic news broadcasts. Though this is thread is never resolved, it is strongly hinted in that local homeless woman CJ is an elderly Claudia Jones. In a lesser work the protagonists solving these mysteries might take center stage, but by confining them to the fringes of the story MariNaomi creates a more textured world for her characters to exist in. The disappearance of Claudia Jones then becomes the kind of small town urban legend teenagers might tell each other with only the reader aware of its larger implications.

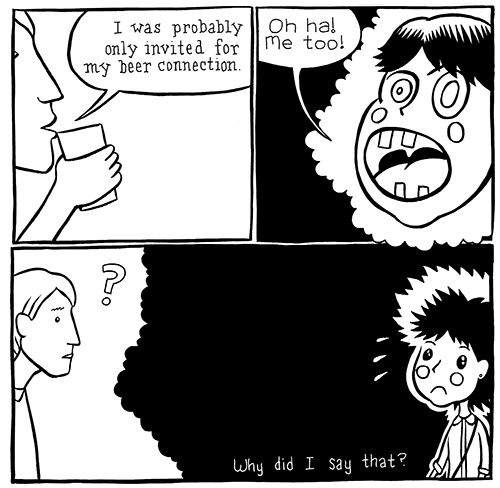

This story of girls being lost to aliens and to teenage ignorance comes together nicely enough through Naomi’s cartooning. Though not as strong as the writing or the pacing, her simplified rendering and composition consistently present the action clearly. Her greatest strength as a cartoonist in Losing the Girl is the way she captures her character’s emotions through their performance. Be it the extreme distortion of Emily’s face when she tries to set up a date with Brett, or the subtler cartooning used to convey Nigel’s naiveté. Rightfully the camera mostly frames just the characters or their faces to highlight this strength of MariNaomi’s craft, though in an odd choice at times their bodies are not drawn into the shot, or characters are exclude entirely in favor of only their word balloons. Such panels can be jarring as so much of what invests the reader into the drama is the emotional performance of the characters that removing even a portion of it lessens its impact.

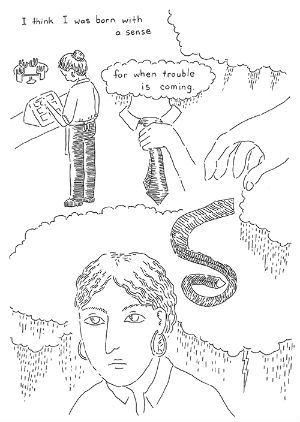

The incomplete nature of some of the drawings is not always a hindrance as MariNaomi’s loose breezy cartooning functions majestically in Paula’s chapter. For this section a more stippled line is combined with panelless page construction so that abstracted visuals intertwine seamlessly with the floating text. Even with almost page filling areas of white, nothing feels unbalanced. The aesthetic of Emily’s section can be equally strong with its effortlessly flowing line and deep areas of black used in a more traditional comics page layout. While Brett’s section shows not only a strong command of watercolor but also of visual metaphor. In a striking full-page splash MariNaomi blends the starry sky into constellations of sperm and fetuses to symbolize the weight of guilt Brett feels having learned of Emily’s abortion. Only Nigel’s section suffers from the use of a distinct aesthetic as the flat digital color compresses everything into a sheet of grey with few black or white highlights.

The incomplete nature of some of the drawings is not always a hindrance as MariNaomi’s loose breezy cartooning functions majestically in Paula’s chapter. For this section a more stippled line is combined with panelless page construction so that abstracted visuals intertwine seamlessly with the floating text. Even with almost page filling areas of white, nothing feels unbalanced. The aesthetic of Emily’s section can be equally strong with its effortlessly flowing line and deep areas of black used in a more traditional comics page layout. While Brett’s section shows not only a strong command of watercolor but also of visual metaphor. In a striking full-page splash MariNaomi blends the starry sky into constellations of sperm and fetuses to symbolize the weight of guilt Brett feels having learned of Emily’s abortion. Only Nigel’s section suffers from the use of a distinct aesthetic as the flat digital color compresses everything into a sheet of grey with few black or white highlights.

The balancing act that MariNaomi pulls of in Losing the Girl is frankly staggering. Art direction quibbles aside, it speaks highly of her abilities as a cartoonist that she can have four completely different cartooning styles co-exist within the framework of the book and have all of them predominantly serve their respective goals. Much of that comes from the confidence she has as a writer to tell a story about teens that could apply to people of any age group.

Other than the character’s ages everything about this story – from the central drama surrounding Emily to the alien invasion subplot – feel right out of a ’90s indie movie sleeper hit about early twentysomethings, in the best way possible. From their voice to their performance, her characters are deeply sympathetic and their struggle deeply relatable. It’s a brilliant choice to get the reader invested in these characters on the small scale so that in the upcoming volumes – when assumedly the science fiction elements take precedence – the drama will be all the more heightened because it is happening to characters we truly care about.

MariNaomi (W/A) • Graphic Universe, $11.99

Review by Robin Enrico