March: Book Two is a phenomenon powered by passion: the passion of one man who devoted himself steadfastly to a better world, and the passion of the team showing why his story is more resonant than ever.

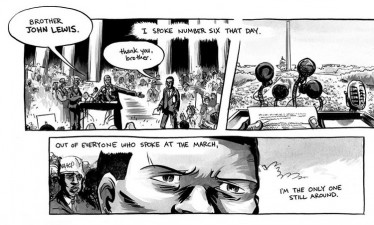

It seems odd to start off a book review with an acknowledgement of the ending, but when that ending is the historic 1963 March on Washington, it’s impossible to ignore. As the only surviving member of the civil rights era’s “Big 6” and a key speaker at the event, Congressman John Lewis is part of a legacy that invites awe and admiration.

It seems odd to start off a book review with an acknowledgement of the ending, but when that ending is the historic 1963 March on Washington, it’s impossible to ignore. As the only surviving member of the civil rights era’s “Big 6” and a key speaker at the event, Congressman John Lewis is part of a legacy that invites awe and admiration.

But at the beginning of the volume, the heroic campaigner is obviously unaware of what his future holds. Instead, Lewis (with co-writer Andrew Aydin and artist Nate Powell) casts the reader into the heady days of his student activism at American Baptist in Nashville. Emboldened by the success of the Nashville sit-in campaign, Lewis and his fellow activists are in the midst of broadening their focus – and coming face-to-face with a hatred that’s darker and more desperate than before.

The heightened stakes as Lewis continues his path to the Lincoln Memorial (interspersed with scenes from President Barack Obama’s inauguration – a day which would have once seemed an impossibility) make March: Book Two even more compelling, inspiring, and suspenseful than its predecessor.

Aydin and Powell don’t shy away from depicting the dangerous circumstances Lewis and his colleagues faced. In a chilling early scene, John rushes to a local fast food restaurant to take over a sit-in after its members are physically harassed by a young waitress. Although John and his companion are outwardly steadfast as the owners turn off the lights and leave, the page pulls the reader into the young men’s creeping uneasiness through whispered, half-heard conversations and the heavy darkness captured by Powell’s intense inks.

Aydin and Powell don’t shy away from depicting the dangerous circumstances Lewis and his colleagues faced. In a chilling early scene, John rushes to a local fast food restaurant to take over a sit-in after its members are physically harassed by a young waitress. Although John and his companion are outwardly steadfast as the owners turn off the lights and leave, the page pulls the reader into the young men’s creeping uneasiness through whispered, half-heard conversations and the heavy darkness captured by Powell’s intense inks.

By the time the full reality of the situation sets in, the event is an awakening not only for the reader, but for John himself: “Were we not human to him?” It’s moments like these that pull March into the ranks of the best non-fiction writing, going beyond the events recorded by history to illustrate powerfully the perspectives of their participants.

This theme is also prevalent in the scenes where the ideals of Lewis and the student movement are stifled by the caution of older leaders. March shies away from myth-building, not only when it comes to Lewis, but also with well-known figures like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and these moments inject much-needed flesh-and-blood into names many know only from textbooks.

Perfection is misleading; seeing real people struggle with their own weaknesses and misgivings is empowering.

Perfection is misleading; seeing real people struggle with their own weaknesses and misgivings is empowering.

Those expecting photorealism to accompany Lewis’s autobiography will probably find that Powell’s cinematic framing is both more dynamic and more emotionally resonant. Scenes like the haunting night-time appearance of the Ku Klux Klan or Lewis’s triumphant footsteps to the podium in Washington are stirringly depicted in a way that feels intensely human.

One of the most interesting points that Lewis, Aydin, and Powell bring up is the importance of dramatization and storytelling itself. Lewis has been vocal about the impact that Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a comic published in 1957-58 by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, had on his own lifetime of activism. Later, during the historic Freedom Rides, Lewis is shocked to hear that a white bus driver has heard of CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality), indicating that their efforts are bringing awareness to the nation.

In the same way, March brings the people and places of one man’s remarkable journey to a new generation of readers – some of whom will undoubtedly find their own lives transformed by the experience.

John Lewis & Andrew Aydin (W), Nate Powell (A) • Top Shelf, $19.95, January 2015.