À La Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time) ranks up there, with War and Peace and Don Quixote, a classic that everyone appears to have an opinion on, but few have actually read. This has as much to do with its length — seven volumes written between 1871 and 1922 — as with the subject matter itself, interweaving the life and times of its unnamed narrator from childhood through adulthood with profound meditations on the meaning of human existence. If one adds the French aristocracy as a setting to this mix, coupled with extensive discussions on art and love, it’s easy to see why academics alone dare to grapple with Marcel Proust.

À La Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time) ranks up there, with War and Peace and Don Quixote, a classic that everyone appears to have an opinion on, but few have actually read. This has as much to do with its length — seven volumes written between 1871 and 1922 — as with the subject matter itself, interweaving the life and times of its unnamed narrator from childhood through adulthood with profound meditations on the meaning of human existence. If one adds the French aristocracy as a setting to this mix, coupled with extensive discussions on art and love, it’s easy to see why academics alone dare to grapple with Marcel Proust.

This is one of the many reasons why Stéphane Heuet deserves to be congratulated. Not only has the French artist dared to turn a beloved epic into a gripping graphic novel, he has — with a little help from translator Laura Marris — managed to do this without compromising the integrity of the original work.

The premise alone is awe-inspiring: to take on something so vast and attempt to breathe new life into it using a visual medium can take a lifetime. The first book of Heuet’s adaption appeared in 1998. It took over a decade and a half for an English translation to appear, which is why the presence of this second volume in such a short span of time has been a surprise.

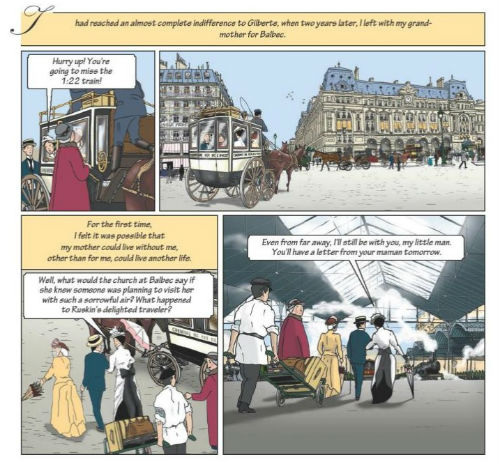

This volume is about adolescence, with all the confusion and exhilaration of that difficult phase we tend to forget the minute it is behind us. The narrator moves on from his infatuation with Gilberte Swann, which occupied much of the first volume, and we are introduced to the young and beguiling Albertine who starts to occupy a larger role as the novel progresses. There are other young women too, as the title In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower makes abundantly clear, and a marked emphasis on emerging sexuality.

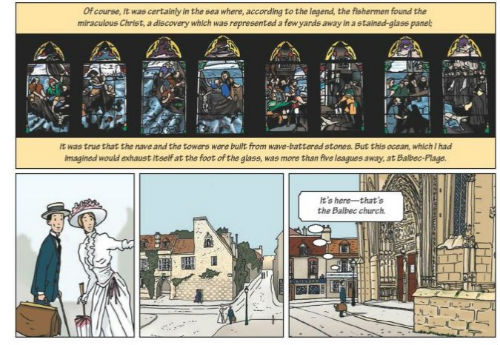

It is important to note that the drawings continue to follow the ligne claire (clear line) style made famous by Hergé and The Adventures of Tintin. This works to the illustrators’ advantage, allowing them to introduce a mild levity to otherwise ponderous themes while lulling the reader into a false sense of familiarity. The style also yields panels of absolute delight, especially when the narrator describes the fictional seaside resort of Balbec.

In her note on the translation, Marris mentions Proust’s “convex lens of yearning through which he examined the world.” This is a telling phrase, given how Heuet transforms that yearning into panels that try and replicate the act of memory, one image triggering another a few pages later. The narrator’s relationship with his grandmother is recreated poignantly, as Heuet is presumably aware of her passing in the next volume. Another thing that differentiates this from the first volume (apart from the obvious change of setting) is what Marris describes as being ‘anchored to the world’ as opposed to being more speculative in nature.

Will Stéphane Heuet and publishers pull it off and manage to publish the existing adaptations of all seven volumes in English? We’re rooting for them, obviously, but Heuet could retire tomorrow and these two volumes alone would still guarantee him a fair amount of gratitude from lovers of literature the world over.

Stéphane Heuet & Stanislas Brézet (Adaptation), Stéphane Heuet (A), Laura Marris (T) • Penguin Random House/Gallic Books, $27.00/£19.99

Review by Lindsay Pereira