In a sharp change of direction from his usual insights into troubled youth, acclaimed cartoonist and publisher Charles Forsman joins the nostalgic trend for low-brow exploitation comics.

I’m sure someone much more perceptive than me has already come up with a generic label for this, but I’ve read a few comics recently – especially out of the US alternative scene – that hark back in a deliberately naive style to the altogether simpler action thrills of the 1980s.

I’m sure someone much more perceptive than me has already come up with a generic label for this, but I’ve read a few comics recently – especially out of the US alternative scene – that hark back in a deliberately naive style to the altogether simpler action thrills of the 1980s.

From work like Benjamin Marra’s Blades and Lasers (Sacred Prism) to Michel Fiffe’s altogether more ambitious and sophisticated Copra, these comics have the whiff of artists returning with a mature skillset to material they might once have scribbled in the back of an exercise book during a particularly tedious lesson.

In an interview with Marra for The Comic Journal a couple of years ago, Matt Seneca talked about the artist’s aesthetic as “an earlier breed of comic-book storytelling reincarnated to take advantage of the modern medium’s disdain for content restrictions.”

Later in the interview, Marra proclaims that “comics should embrace the idea of being exploitation, low-level, gutter trash entertainment.”

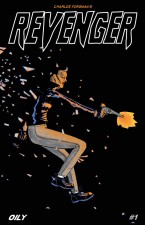

Anyway, Charles Forsman is the latest comicker with a low-brow generic itch to scratch. In a major departure from the tales of troubled youths (TEOTFW, Celebrated Summer, Teen Creeps, Luv Suckers) for which he has been rightfully acclaimed, he’s moved on to Revenger – a comic that marks a progression in style as well as a change of subject.

The blurb on the inside cover gives the reader most of what they need to know for the story to come:

Revenger travels a broken United States helping the weak and exploited through the use of extreme violence. When all else fails, Revenger evens the score.

The book starts with a context-free action sequence that very much sets the tone: the Revenger takes down a vicious clown gang while recalling the painful death of her lover.

It also highlights the key stylistic changes in Forsman’s approach to the book. Most obviously, the book is in full colour, opening with a sharp neon pallette redolent of the decade in which it’s set. Together with a bolder, clearer line, it marks a firm step away from the cartoony naturalism of his earlier work to something bolder and more deliberately ‘artificial’

Anyway, after receiving a call on her 1-800 hotline, the Revenger heads to Neptune CA on the trail of a missing girl. After some characteristically forthright investigation, the trail soon leads to grisly local boss Mr Groan, who is using the town hotel for activities that might get it some one-star reviews on Trip Advisor.

As suggested by Matt Seneca’s quote above, Revenger harks back to a more simple age of action comics that didn’t rely on a lot of moral nuance – just the wish-fulfillment action that (whether we want to admit it or not) probably drew a lot of young male readers to comics in the first place.

However, even if Revenger lacks the skilled characterisation and empathetic insight that defined Forsman’s earlier work, there’s always pleasure to be had in watching a skilled creator knowingly revisit this kind of material; their enjoyment shows through and pushes the reader’s nostalgia buttons, as well as their own.

Even though I’m generally the first to harumph at the spluttering fury of fan entitlement whenever a creator moves in a new direction, I have to admit that I’ve occasionally felt the urge myself – to a lesser degree – with some of Gilbert Hernandez’s more extravagant diversions.

However, creators should – obviously – be free to do what they wanna do. And in the gloriously accessible and egalitarian medium of comics, we have the perfect laboratory in which comickers can experiment and take off in any direction they choose.

So go ahead, Chuck, and scratch that itch. It might not be my cup of tea, but I’ll be waiting for your at the other end.

Charles Forsman (W/A) • Oily Comics, $2.00 (digital), $5.00 (digital and print)