Today at BF we’re presenting an unseen interview with creator Sean Murphy (Punk Rock Jesus, Hellblazer, The Wake) conducted by guest contributor Zoran Djukanovic. While the content is less recent the insights into Murphy’s creative process on books like Hellblazer, The Wake, Joe the Barbarian and Punk Rock Jesus is timeless. Over to Zoran…

Some time ago I met Sean Gordon Murphy in Makarska, Croatia. Before we met I had an extensive email conversation with this exceptional artist; one who creates work that is a benchmark of non-standard approaches in the field of comic books.

You have worked with the first league of writers in the field of comics – among them with Jason Aaron, Grant Morrison, Scott Snyder and Mark Millar – as well as a 100% in-house storyteller. Within less than decade you reached a point of artistic maturity and became an artist in high demand. You developed a very expressive reality-based cartoony style with a lot of loose density of thin lines. Is that the reason that you don’t trust inking to anyone other than you?

SEAN GORDON MURPHY: I started inking myself because there’s a pencilling and inking rate in the US, and you’ll be paid more if you can do both. But I quickly fell in love with the brush and the quill, and soon I was able to pull back on my pencils while allowing the inks to become more expressive. I’ve never had an inker, and I have no plans to ever need one.

You repeatedly mention the three core influences on you – Bill Watterson, Jorge Zaffino and Sergio Toppi, three masters of style, quite remote from each other. Could you be more specific, what you see or feel in their work?

Calvin and Hobbes is my favorite comic because of both the writing and drawing. And I admire Watterson a lot because he was able to draw both cartoony and realistic in the same strip, which isn’t easy. And he did it all himself, which is impressive to me.

Calvin and Hobbes is my favorite comic because of both the writing and drawing. And I admire Watterson a lot because he was able to draw both cartoony and realistic in the same strip, which isn’t easy. And he did it all himself, which is impressive to me.

Zaffino I admire because he was constantly exploring looseness and expression with a heavy use of black, which I find endlessly fascinating. Being clean is the obvious path for most artists, but Zaffino shows me there’s so much more to explore when you’re building beauty out of messiness.

My obsession with Toppi is a bit like Zaffino (I believe he was a Toppi fan as well), the main difference being that Toppi was less interested in storytelling and more interested in illustration. While I focus more on storytelling, I keep Toppi in mind a lot when I’m working, trying to make each page valuable as a standalone piece as well.

We share a love for Breaking Bad. What attracts you to that TV show?

I’m drawn to contemporary stories more than science fiction ones, and I’ve always found crime interesting. Breaking Bad is obviously a masterpiece, but the other thing I love about it is that it breaks the rules of American TV in that it’s not serialized like other shows. It forces viewers to wait months and months until more episodes are ready, and those people are loyal enough to come back. It reminds me of comic readers “trade-waiting”, which is a departure from monthly title collecting. Those are the readers I’m after.

Your personal drawing style exploded with Hellblazer, when you became the artist you are. The only comparable “style explosion” I could find is within Shade the Changing Man where Chris Bachalo’s style explosively emerged. Also, your composition of the page reached its maturity on the pages of Hellblazer. What happened at that moment, which seems to me so decisive?

I get compared to older Bachalo a lot, but I never saw his older stuff until a few years ago (when I first saw it, I thought “wow it looks like I’ve been stealing from him!”). I think we just happened to both follow the same teachers like Toppi and Sienkiewicz. What made me take that path was that I was tired of trying to draw a “house” style–it’s that basic American comic style you see all over mainstream superhero comics. I was overflowing with the desire to start using a million different rendering techniques, and on Hellblazer is when the dam broke.

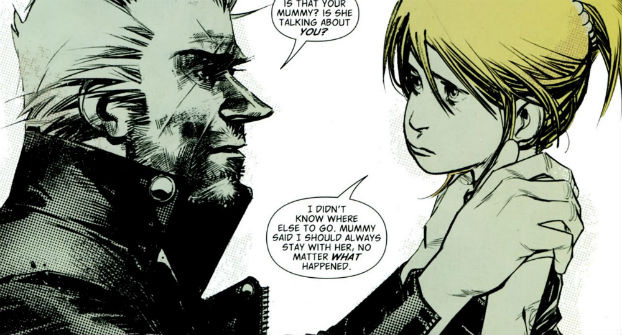

One of the most impressive aspects of your work is that you are a sequence master, creating sequences that stretch over several pages. Some of them remain stuck in reader’s memory, like the prologue in your collaboration with Grant Morrison Joe the Barbarian; a real bravado sequence that stretches from the graveyard, then moving through the house (we could also hear the rain!), until entering another world. Aside of constructing the entire house blueprint, what was your approach to make such unforgettable sequence of eighteen pages that starts and ends with the two-page spreads? I am aware that you wrote an excellent essay in the afterword for the Joe the Barbarian trade paperback.

I think what helped make that issue work was my decision to place the character in a town near my home (Grant didn’t specify a setting). I was then so emotionally invested that I ended up conveying a lot of mood into the scenes. The trick was trying to make readers care. With 5 pages of a kid walking into a house, I didn’t want to risk boring everyone.

Thank you for asking that. Even though there were 8 issues, issue #1 is the only one I hear people talk about.

Sample image from Joe the Barbarian

In your afterword, when describing a mesmerizing camera move through Joe Manson’s house, you said your main concern is always clarity. At the same time, “your camera” creates hypnotic storytelling! Is this you giving us a hint: “sometimes too many lines… I work so fast… thousand decisions…”? What is the secret… could you touch upon that marvelous paradox between clarity and the hypnotic in your style?

Clarity is key, but it can also be boring. Once I’ve made sure the panel is clear, I’ll start rendering and doodling until it holds more visual interest. The risk is stopping before it gets out of hand. Every once in a while, I’ll have gone too far. It helps to work on the entire page as a whole, rather than focus in on one panel. Skipping around helps me find mistakes while also making it easier to decide when I’ve put in enough detail.

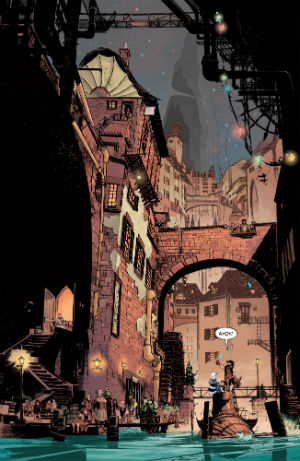

Variations of the stairs theme looks to me as an ever occurring motif in your work (Hellblazer, American Vampire: Survival of The Fittest, Joe the Barbarian, Punk Rock Jesus, The Wake – only not in Off Road, though). Am I reading something in or is there a fascination with stairs and ladders (recalling movie classics like The Spiral Staircase and Vertigo)?

Backgrounds are more interesting when you add places for the characters to go. Even if a character doesn’t use the element, I like adding stairs, doors, ladders, and fire escapes into many of my pages. Comic artists tend to think of the world as being on one level, so I try and make an effort to increase the visual interest by layering the horizon.

More intricately rendered architecture from Joe the Barbarian

Is it a part of your broader visual strategy; a sort of “defamiliarization (estrangement) of the space”? The way you create suspense by composing the pages that depict the apartments, rooms, corridors and stairs (also scenes within vehicles; people surrounded with crowded and abandoned technological objects and architecture)… is it little bit like Giovanni Battista Piranesi prisons, or M. C. Escher architectural puzzles?

Yes. Drawing in such a way makes it possible to enjoy the artwork if you read it multiple times. Like any good movie, I like comics to have enough complexity where the reader will discover new things and different layers to the art they didn’t see the first time.

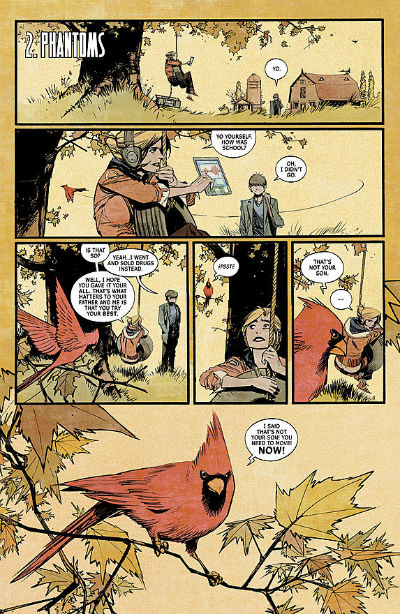

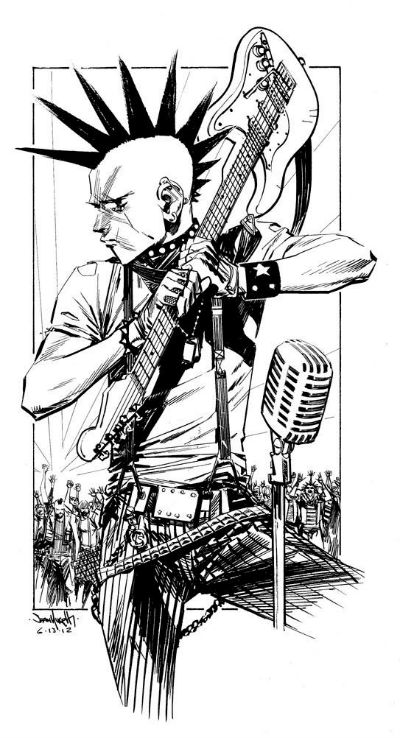

Around 2003 as a raised catholic you became an atheist. It affected your creator-owned Punk Rock Jesus (below). How much is that autobiographical in content?

I’ve described it as an autobiography disguised as science fiction. While there aren’t any specific events in the book taken from my life, I designed each character as a vehicle for a certain way I feel about life and religion. For example, Thomas thinks more like how I used to think (although I wasn’t violent), the doctor has my love of science as the replacement of religion, and the young clone expresses the exact frustration I did when I lost my faith.

If there was a new edition of Punk Rock Jesus would you personally like to see it in color?

No. But if someone offered to color it and publish it that way, I’d love to see it. Many of my readers love color even though I’m more into black and white.

I have huge respect for your attitude of gauging success in the following order: self-satisfaction, critical acclaim, sales and then peer approval. Moving back to sales, could you compare sales of your work, which title sold the best?

The Wake is the biggest seller so far. This is the first big financial hit–the others did well, but they didn’t raise eyebrows like The Wake. Punk Rock Jesus is outselling Joe in some countries, although I’m not sure that’s true in the US. Hellblazer and Vampire come after that. And the rest of the small stuff I did over the years had medium success.

You once described the American Vampire: Survival of the Fittest as a basically Indiana Jones-like story. Did it help you to relax, and forget your ‘genre reservations’ towards horror in its pure form?

Yes. I don’t usually enjoy horror. Drawing monsters has always been hard for me. Which is odd because I seem to be involved in many books like that lately.

More Punk Rock Jesus interior art

You frequently stated that you prefer science fiction adventure type of stories to horror. Did you consider yourself “misunderstood” when getting frequent offers to do horror because of your intensive, powerful use of black color (a Zaffino influence?), or have you found “a genre reconciliation” in The Wake?

People seem to equate “lots of blacks” to horror. Even though I use a normal amount of black by European standards, I stand out when it comes to the US. I wish I’d been offered more noir and crime stories over the years, but there’s always been a big horror market. “Genre reconciliation” is a good way to describe how I approach it. For example, I tend to think of The Wake as a sci-fi story rather than a horror story. It helps me get through projects I might not otherwise enjoy.

Not many artists have a feeling for the artificial/technical and natural/pastoral at the same time. From Hellblazer to The Wake you show that affinity and ability. OK, a little bit of pocket psychology… what are the childhood origins of that?

I was raised in a small town next to a lake, so I have a large appreciation of nature. But I wanted to draw tech like the best Manga artists. I try to avoid having an Achilles Heel when it comes to art–I want to handle everything well so I can compete with the best artists.

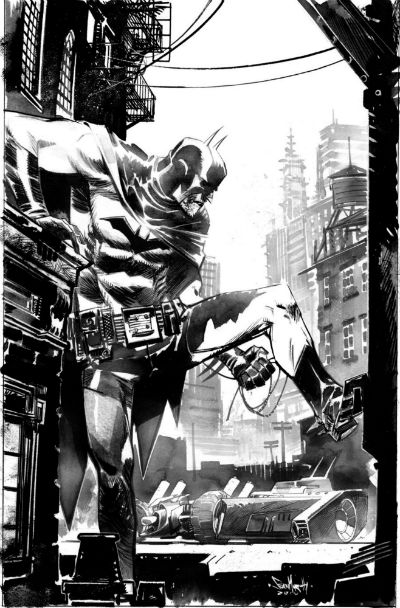

Atmospheric visuals from The Wake

Are you familiar with Dan Barry’s work on Flash Gordon (particularly his brilliant period between 1951 and 1963)? The beauty of oceans, water and underwater scenes in The Wake reminds me on the SF adventure type of stories that Barry was capable to evoke.

Yes, I love Dan Barry. A lot of the artists in that generation were very good at water and nature. Perhaps better as a whole then we are now. I’m not sure why that might be.

There is an unusual balance between the modern and the classical in your stylization. Also between the angry and sudden, on one side and the quietness and peacefulness, on the other side. Would you consider your drawing approach in any of these terms?

Very nice of you to say! Balance like that is very important for me–“peaceful” means more when it’s juxtaposed with “violent”, and “modern” means more when it’s set aside “old fashioned”. Being good at one thing and not the other would make the artist unbalanced, perhaps leading to him being typecast. Which I’d like to avoid.

You have expressed a love for tiny panels with smaller action. What is the storytelling function of that within your visual narration and page composition?

For me, a small panel is a nice visual half-beat of a drum. It’s a nice way to break up a predictable rhythm in a song. If there’s a way to introduce that (it’s often something I’ll add, as writers don’t tend to think in terms of “small moments”), and I have the energy, I’ll put it in.

Murphy’s most recent project with DC

Drawing and writing in the comic medium is a symbiotic process, regardless of whether it happens via one single person, or between two human beings. Are you empathetic enough to ignore the difference? Do you always prefer a creator-only role?

I prefer to do it all myself. Once I’m done with my next two projects, I plan on writing for myself for a long time. The symbiotic process is more unfettered when it’s all in the same person. I might not be as good a writer as Scott Snyder, but what I lack in writing I can make up for with art and having a cleaner symbiotic process within my own head.

The team jamming (when and if that happens) between artist and writer includes the colorist as well. You do not seem a possessive artist; you allow yourself be a part of the creative chain and a full part of the group.

I am careful to select people I trust. I’ve had trouble trusting groups and projects in the past, so one career goal was to take better care in choosing what I’ll get involved with.

In your poster for MaFest you included Cola, a polar bear from Punk Rock Jesus. In Joe the Barbarian you inserted specific toys from the ‘70s and ‘80s. There are numerous examples. Your work is highly referential. Is that something you particularly enjoyed?

I add that stuff because I want to have fun. The entire page will come out better if I have more personal investment in the subject matter. Outside of Punk Rock Jesus, usually I’ll add that stuff without asking permission.

Anything else you would like to add?

Great questions! I’m honored by the amount of research you did.

You can follow Sean Murphy on Twitter here and visit his online store here.