The last time we featured the work of William Powers at Broken Frontier it was for a zine that encapsulated a very different form of graphic storytelling. Never Been Reborn adopted the surrealist cut-up writing technique by appropriating text from an obscure novel Powers obtained from a charity shop and placing the rearranged words and text into alternative visual sequences. The result was eerie and hypnotic, and one about which I said “springing forth from words repurposed, reapplied and refashioned, this is a comic where narratives exist both within and outside of each other and where the metaphorical and the literal merge.”

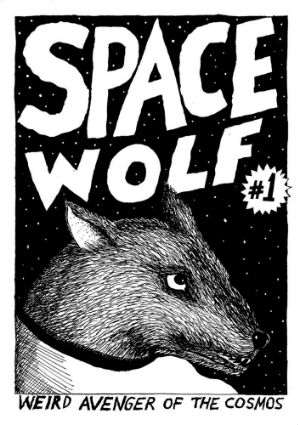

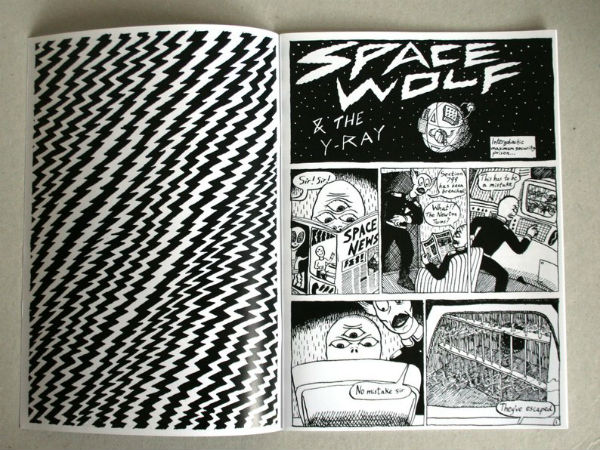

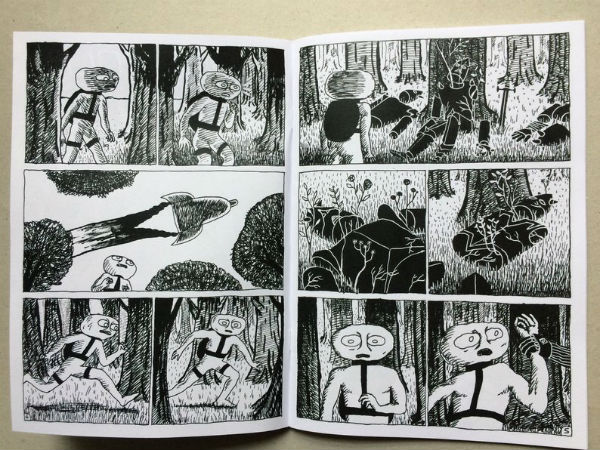

Powers is a creator of diverse approaches, then, and today’s offering is perhaps somewhat more traditional in structure. Space Wolf is influenced by the art of Basil Wolverton and a classic era of science fiction comics storytelling. That’s not the only way in which the comic has an old school vibe though. Each issue to date has been a self-contained story; something that the US genre comics industry largely abandoned many years ago but makes Space Wolf an accessible read to anyone picking up an individual issue.

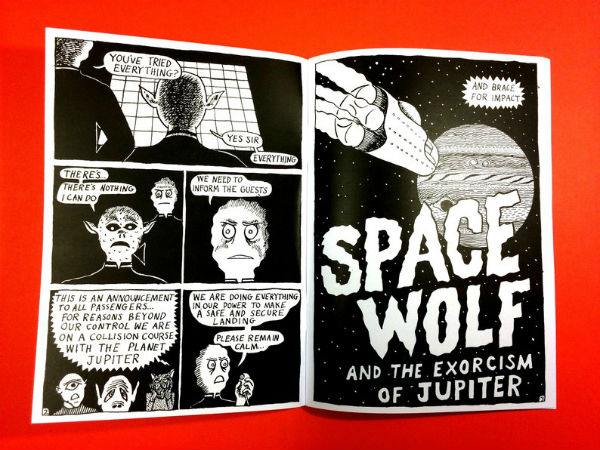

Reading all three stories in one sitting, Powers’ growing confidence in his delivery is self-evident. The titular protagonist is a galactic hero and adventurer who, it is hinted, has a far less benevolent and darker past. While each story is simple in plot it’s as much the era they’re paying homage to and their comfort reading nature as their storylines that makes Space Wolf such a fun read. In #1, for example, Space Wolf takes on two escaped prisoners and their boss Mr. Xittleton in a case of a stolen resurrection ray that feels a little EC Comics in conclusion while in #2 he must rescue his old mentor from the villainous Subtora on the planet Venus.

It’s the third issue, though, where the series really hits its stride as, in pursuit of another cosmic criminal, Space Wolf is drawn to a seemingly abandoned planet. Here he encounters the mysterious Knights of Eos and secrets of his past redemption are revealed. This ecological parable sees Powers subverting page structures in its final pages as speech balloons and their placement become integral to the depiction of a wider, less definable, natural intelligence. It’s also an issue that subtly reveals whole new layers to Space Wolf’s origins without the need for overwrought, melodramatic flashbacks. Earlier visual storytelling is occasionally rawer in presentation, and dialogue a little stiff in the opening chapter or two, but by the time we get to the ‘Knights of Eos’ it’s clear that Powers is not just finding his stride with his pacing, layouts and characterisation but also thoroughly enjoying himself.

On a more pragmatic level – and this is a point that relates to all self-publishers – I would suggest that as much as it’s difficult to let go of traditions like numbering in the small press world it may be a necessity. It creates an impression for readers that they need to start reading at a certain point and puts off small press stockists in shops who have to balance limited shelf space with a perceived need to keep all copies in stock. Titling individual issues rather than numbering them on covers may be more effective in increasing a readership.

Regardless, Space Wolf is a stellar romp of a comic but one with a degree of often unspoken poignancy at his heart. If small press escapism is what you’re looking for you can’t go far wrong here.

For more on the work of William Powers follow him on Twitter here and visit his online store here.

For regular updates on all things small press follow Andy Oliver on Twitter here.

Review by Andy Oliver