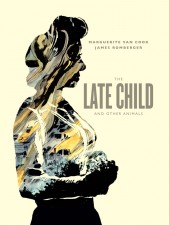

In The Late Child and Other Animals, Marguerite Van Cook and James Romberger team up again to produce a lyrical, visceral and expressionistic memoir of a difficult childhood.

Even if they’d never produced another page together, the names of James Romberger and Marguerite Van Cook should be writ large in comics history for one achievement alone: their blistering work on 7 Miles a Second, adapted from the life and work of the late artist and Aids activist David Wojnarowicz (a friend of the couple’s from the East Village art scene of the 1980s).

However, fortunately for us, Romberger and Van Cook have collaborated again on another major and even more personal work – The Late Child and Other Animals.

However, fortunately for us, Romberger and Van Cook have collaborated again on another major and even more personal work – The Late Child and Other Animals.

This autobiographical suite of five stories traces the circumstances surrounding the birth and development of the young Marguerite, from the tragic twist of fate that leaves her the daughter of a stigmatised single mother to her solo efforts to propel herself from childhood into adulthood.

It straddles the tumultuous middle decades of the twentieth century, from Hitler’s blitz being unleashed against the British naval city of Portsmouth to the less bloody but almost equally momentous social upheaval of the Paris Spring of 1968.

It might seem a little reductive to highlight the division of labour behind the work, but breaking The Late Child down into its constituent parts might help to demonstrate how the whole fits together as a dazzling example of the ambitious and expressionistic narratives to which comics are so particularly suited (but which they all too rarely achieve).

It might seem a little reductive to highlight the division of labour behind the work, but breaking The Late Child down into its constituent parts might help to demonstrate how the whole fits together as a dazzling example of the ambitious and expressionistic narratives to which comics are so particularly suited (but which they all too rarely achieve).

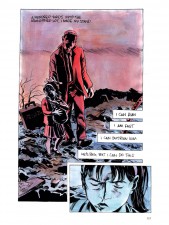

The foundation of the work is Van Cook’s words – a variously lyrical and visceral voice that sings off the page. Throughout the book she also provides little tactile cues that manage to stimulate vicariously the senses that even her and Romberger’s art can’t reach: the sense of dirt scratching her face; the prick of a blackberry plant.

The text is then broken down by Romberger, whose layouts, brushwork and slightly off-kilter lettering give the work a palpable dynamic urgency. Finally, as in 7 Miles a Second, the pages then go back to Van Cook for the addition of vivid, mesmerising colours.

The close collaboration means there’s a rich unity to the work, thematically and stylistically. Natural imagery abounds throughout the book; even in the very first pages, resilient Buddleias manage to bloom on the bomb sites of Portsmouth. It comes as little surprise when we discover that the poetry of Ted Hughes featured prominently in the young Marguerite’s education.

The close collaboration means there’s a rich unity to the work, thematically and stylistically. Natural imagery abounds throughout the book; even in the very first pages, resilient Buddleias manage to bloom on the bomb sites of Portsmouth. It comes as little surprise when we discover that the poetry of Ted Hughes featured prominently in the young Marguerite’s education.

In the world Marguerite discovers, nature is both beautiful and threatening. In the third part of the book, ‘Arreton Downs’, she recalls the apparent rustic idyll of the Isle of Wight – just a short ferry ride away from Portsmouth, but different enough from the grimy, bomb-torn city to seem like another world.

Frolicking in the summer fields, the eight-year-old girl gains a sense of the busy fecundity of the natural world: “I never knew the world was so alive… Now it was as though I was one with the place. As if I could understand the rural conversation”.

However, while exploring the island she has something of a “peak experience” that hints at the true sublime power of nature; for all its beauty and richness, it retains the power to hurt you and put you in your place. Plunged into a sudden sense of isolation and vulnerability, she finds the rural idyll turning into a world of threat, embodied in the merciless summer sun and the harsh wheat stalks that cut her legs.

However, while exploring the island she has something of a “peak experience” that hints at the true sublime power of nature; for all its beauty and richness, it retains the power to hurt you and put you in your place. Plunged into a sudden sense of isolation and vulnerability, she finds the rural idyll turning into a world of threat, embodied in the merciless summer sun and the harsh wheat stalks that cut her legs.

‘The world sprawled away in every direction. No shade. No refuge. Just the searing of the sun and acres of brutal stems… Never have I felt so small, not before, not now. That instant stole my identity and everything I thought I knew about life, my place in the world.

Taking place almost exactly half way through the book, this visionary experience marks a turning point: in the terms of William Blake, it represents the young girl’s shift from innocence to experience. This trajectory continues across the remaining two parts, through a terrifying encounter with a predatory paedophile in the fourth chapter, ‘Nature Lessons’, and then finding herself on the very cusp of adulthood in part five, ‘Maupassant Compris’.

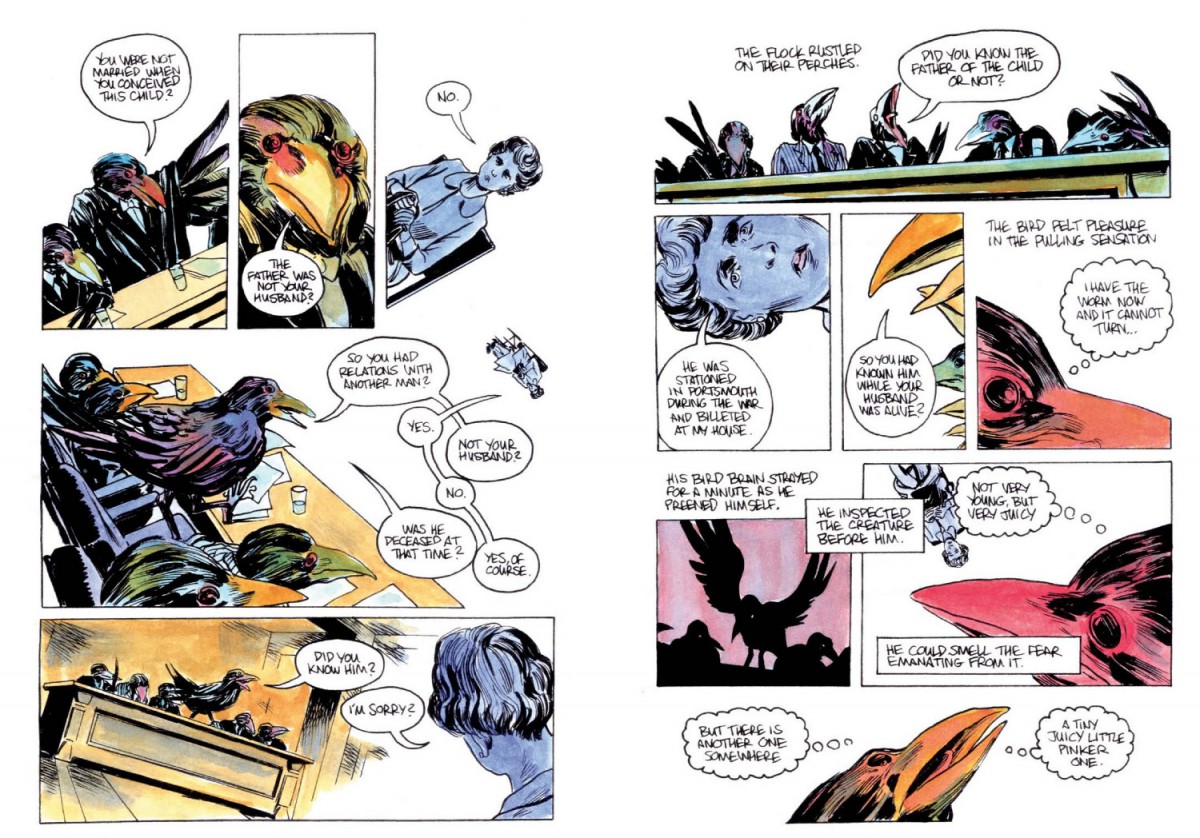

The natural imagery takes a more vivid form during a virtuoso sequence in the second story, ‘The Outing’. After the largely naturalistic depiction of life on the home front in ‘Hetty’s War’, here we move into a fuller exploration of what the comic form can do, going far beyond the constraints of the ‘cinematic’ storytelling that defines so many comics.

As Hetty faces a panel of men who presume to judge her moral suitability as a mother, Van Cook and Romberger reimagine the officials as a murder of voracious crows, eager to ‘devour’ the vulnerable young woman and her child. The creators use the expressionistic possibilities of comics to get inside the characters; as Hetty’s humiliating inquisition grinds on, her senses of scale and orientation go out the window.

These episodes all add up to a powerful and timely theme: female vulnerability in the face of a rigid and judgmental patriarchy. Even after Marguerite’s terrifying encounter with the pervert, Hetty daren’t make much of a fuss, aware that it will attract unwanted attention to her status: “A single unmarried mother was fair game”. The young Marguerite begins to sense the shame and embarrassment that Hetty seems to be personifying in her illegitimate daughter.

The book’s conclusion, as the teenage Marguerite spends summer en vacance with a friend’s family in France, isn’t quite unexpected enough to be truly shocking, but it’s certainly upsetting and unsettling, perfectly reflecting her earlier observation that “The adult world was barbarous”.

The book’s conclusion, as the teenage Marguerite spends summer en vacance with a friend’s family in France, isn’t quite unexpected enough to be truly shocking, but it’s certainly upsetting and unsettling, perfectly reflecting her earlier observation that “The adult world was barbarous”.

However, it seems to mark a rite of passage for the young woman, who is now prepared to face that adult world – with some poise, a single-page, single-image coda suggests.

This is a piece of work that’s as rich, varied and almost overwhelming as the multi-course farmhouse feast that Van Cook evocatively describes in the final section. Coming after Fantagraphics’ republication of 7 Miles a Second, I hope it heralds the start of a new chapter in the partnership between its creators and its publisher.

Marguerite Van Cook (W/A), James Romberger (A) • Fantagraphics Books, $29.99, November 2014.

A definite must-read!