Noah Van Sciver delivers an intense and claustrophobic portrait of a dysfunctional father-son relationship.

Oily Comics (the mini-comics vehicle of cartoonist Charles Forsman) may have changed its publishing model of late, but The Lizard Laughed, by alt-comics notable Noah Van Sciver (The Hypo, Blammo), shows that Forsman’s eye for quality remains the same.

The 28-pager (behind a stylish risographed cover) tells the story of Harvey, a seemingly directionless middle-aged man who has ‘wound up’ in New Mexico, and his adult son Nathan, who he hasn’t seen since walking out on his family when the boy was nine years old.

Van Sciver’s style is intricate and textured but also clear, harnessing a strong storytelling intelligence; several thematic threads are subtly woven into what is essentially an intimate vignette of a brief encounter between two men.

For example, as Harvey hangs around the bus station awaiting Nathan’s arrival, a poster behind him asks ‘Where will the open road take you?’ The irony is subtle but clear: road trips and life in the great natural theatre of New Mexico should equate to a sense of freedom, but it soon becomes obvious that both Harvey and Nathan are trapped in their lives.

For example, as Harvey hangs around the bus station awaiting Nathan’s arrival, a poster behind him asks ‘Where will the open road take you?’ The irony is subtle but clear: road trips and life in the great natural theatre of New Mexico should equate to a sense of freedom, but it soon becomes obvious that both Harvey and Nathan are trapped in their lives.

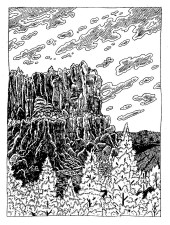

The book’s title comes from a legend apocryphally attached to an unusually shaped rock formation that they see while out on a hike (an ill-judged attempt by Harvey to bond with his son). The story is that of a lizard who stood still and laughed at the Creator when it ordered him to move, and was turned to stone in punishment. Again, the parallel with the state of petrification affecting Harvey and Nathan is clear but not laboured.

Van Sciver’s narrative skill extends to characterisation. Harvey is a 24-carat dick who refuses to take responsibility for his actions. When he discusses walking out on Nathan’s mother, he says, shamelessly, “Obviously, with your mother I had to practically flee in the middle of the night!”

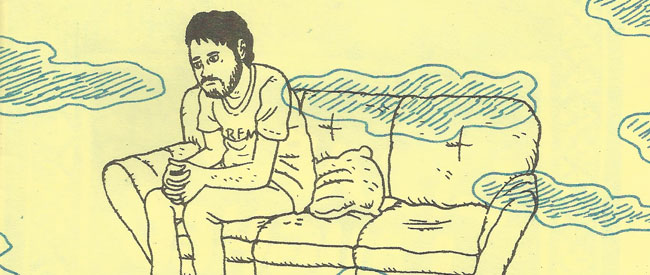

Nathan, meanwhile, is a bit more of a cypher. In appearance like an altogether more intense version of Bret from Flight of the Concords, it’s hard initially to ascertain what he wants from the encounter with his father, or his life more generally.

Recounting where his life is at the moment, he reverts to archetypal slacker boilerplate: “Now I’m just kind of travelling around. Trying to find myself, I guess”. However, the damage caused to him by Harvey’s desertion becomes increasingly apparent.

This is very much a story of what happens when men are left on their own for too long. Even though Harvey is apparently in a relationship, his partner – Marnie – has stormed off after learning about the existence and imminent visit of Nathan. And even though he’s initially shocked to hear that his son’s ‘angel mother’ has died, it doesn’t take him long to slip into some inappropriate recollections about her physical attributes.

Meanwhile, Nathan reveals that he was also engaged at one stage, but “Thank God that didn’t work out”. Harvey’s outlook on relationships is similarly short on sentimentality: “Even if it’s not some ideal romantic situation, it’s preferable to being alone… At least for tax purposes.”

However, the awkwardness of their relationship reaches breaking point when Nathan starts to grill Harvey about his desertion and the hardship he and his mother faced as a result (“Not having you around really fucked me up”).

In the book’s toughest scene, Harvey again abdicates any responsibility: “You’re a grown man now, Nathan. I’m sorry for any problems you have, but part of being an adult is to stop blaming your parents for whatever shortcomings you have. That’s pretty basic”.

A silent drive back and an uncomfortable visit to a bar indicate that their relationship has probably run its course.

A silent drive back and an uncomfortable visit to a bar indicate that their relationship has probably run its course.

All of this leads up to a surprisingly tense climax. I won’t spoil it, but the comic ends with a telling final image: the eternal landscape of New Mexico, with no trace of human presence.

In his intimate study of an estranged father and son, Noah Van Sciver deftly highlights the rough edges of male relationships and the apparent inconsequentiality of our brief lives in the face of cosmic time and nature’s impassive permanence. This is a little gem of a comic.

Noah Van Sciver (W/A) • Oily Comics, $5.00 (print & digital), March 2014

I am anxiously awaiting his collection from Adhouse Books.