A compelling distillation of the character study that is at the true heart of Hugo’s novel.

A compelling distillation of the character study that is at the true heart of Hugo’s novel.

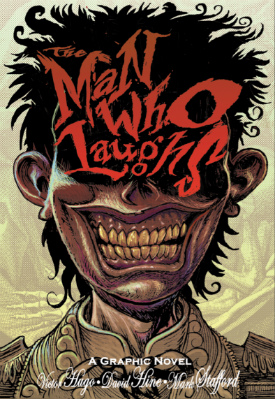

Mention Victor Hugo’s 1869 novel The Man Who Laughs to a mainstream comics fan and the chances are their knowledge of it will go no further than the influence the 1928 film adaptation had on the creation of ultimate Batman villain The Joker. Indeed, even among aficionados of Hugo’s work, the book remains forever in the shadow of his more well-known Les Misérables and Notre-Dame de Paris (or The Hunchback of Notre-Dame in the English-speaking world).

Those who have attempted to slog through the original will have an inkling as to why this is. The Man Who Laughs is replete with discursive digressions on the British social structure of the time that threaten to swamp the very humanity of the book with their excessive, sometimes tedious detail. Had writer David Hine and artist Mark Stafford approached their SelfMadeHero graphic novel imagining of the book in an old school Classics Illustrated manner then this could have made for a rather dry and unabsorbing read. Fortunately Hine cannily elects, instead, to concentrate on the tragic tale at its centre, and the more cutting elements of Hugo’s social commentary therein.

Those who have attempted to slog through the original will have an inkling as to why this is. The Man Who Laughs is replete with discursive digressions on the British social structure of the time that threaten to swamp the very humanity of the book with their excessive, sometimes tedious detail. Had writer David Hine and artist Mark Stafford approached their SelfMadeHero graphic novel imagining of the book in an old school Classics Illustrated manner then this could have made for a rather dry and unabsorbing read. Fortunately Hine cannily elects, instead, to concentrate on the tragic tale at its centre, and the more cutting elements of Hugo’s social commentary therein.

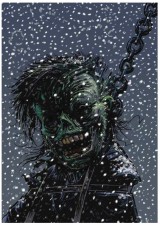

Set in the early part of the 18th century, The Man Who Laughs recounts the life of the unfortunate Gwynplaine, mutilated as a boy by a band of travellers known as the Comprachicos who disfigure children in order to make money from them as freakish attractions. In his case his face has been carved into a rictus grin. Abandoned by his captors in a snowstorm, Gwynplaine stumbles upon the caravan home of the philosopher Ursus and his domesticated wolf Homo. Ursus takes in the deformed youngster and a blind baby girl he found along the way, and an unlikely family unit is formed.

As the years pass, and both children grow to adulthood, Gwynplaine and the unseeing Dea fall in love and the trio continue to earn a living from the morbid fascination that audiences have for the young man’s grim visage. But fate has other plans for the threesome as the Laughing Man’s true lineage becomes apparent. With a past steeped in conspiracy and plotting, and his noble heritage revealed, Gwynplaine’s elevation to the upper reaches of society casts him adrift from the only people he has ever truly loved…

The Hine and Stafford partnership is one that has continued to grow in the two years since SelfMadeHero published The Man Who Laughs, with their current projects including a contribution to the upcoming Broken Frontier Anthology and ‘The Bad, Bad Place’ in Soaring Penguin Press’s Meanwhile… anthology. It goes without saying that, as with any project of this nature, the fundamental question of exactly how a story should be translated from one medium to another is a thorny one.

Should the adaptation be as literal as feasible in order to portray the original author’s intent as accurately as possible? Or is it legitimate to play to the strength’s of the new medium, capturing the thematic essence of the source material while utilising the unique storytelling opportunities inherent in the destination form? Hine makes the sensible choice, eschewing dull abridgement for passionate refinement, and shearing the narrative of some of Hugo’s superfluous diversions from his core storytelling flow.

And it’s here where the synergy between Hine and Stafford becomes most apparent as their adaptation positively embraces the potential of the comics page. The morbid tragi-comedy of the Comprachicos’ ship as it slowly disappears beneath the waves, for example, which is so brilliantly paced from panel to panel. Or the dramatic lead-in to the reveal of Gwynplaine’s horribly butchered face. There’s something quite instinctive about the pair’s partnership; Stafford often allowed to run with events silently and evocatively communicating the tone and atmosphere of entire sequences without the burden of Hugo’s heavy exposition being crammed into each image.

There’s an almost cartoon grotesqueness to Stafford’s caricatured realisation of the sprawling cast of characters that is nevertheless disquieting and disarming in equal measure. His ability to imbue even the most seemingly innocuous details with a deliciously sinister intent is an always hypnotically unsettling element of his work but here it mirrors the skewed morality of the world of The Man Who Laughs.

It’s a constant reminder that Gwynplaine, Ursus and Dea’s story is a reflection of the greater themes of the book in microcosm. The decent and the oppressed doomed to be trampled under the relentless march of the class corruption and social inequality that is so monstrously represented by those in the supposedly cultivated world that Gwynplaine finds himself thrust into. Organic in appearance, and yet meticulously constructed in design, there’s a distorted and misshapen beauty to Stafford’s melancholic layouts.

It’s a constant reminder that Gwynplaine, Ursus and Dea’s story is a reflection of the greater themes of the book in microcosm. The decent and the oppressed doomed to be trampled under the relentless march of the class corruption and social inequality that is so monstrously represented by those in the supposedly cultivated world that Gwynplaine finds himself thrust into. Organic in appearance, and yet meticulously constructed in design, there’s a distorted and misshapen beauty to Stafford’s melancholic layouts.

The triumph of this reworking is Hine’s understanding that adapting a novel to the comics form is about exploiting the possibilities of the latter medium and not about subduing them under the weight of the original source material. The Man Who Laughs is a compelling and emotionally absorbing distillation of the character study that is at the true heart of Hugo’s novel.

David Hine (W), Mark Stafford (A) • SelfMadeHero, £14.99

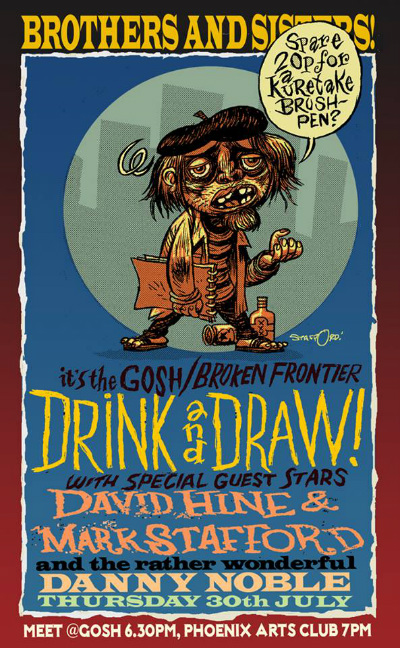

David Hine and Mark Stafford are the guest creators, alongside regular artist-in-residence Danny Noble, at the next Gosh! Comics/Broken Frontier Drink and Draw this Thursday 30th July. David and Mark will be signing copies of The Man Who Laughs at Gosh! at 6.30 that evening.