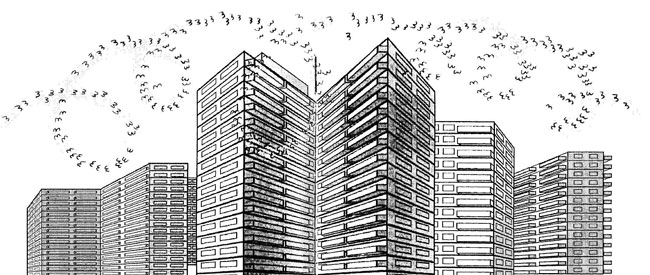

With a strong sense of design and a bold cartooning style, Katherine Verhoeven’s apocalyptic tale of kids with supernatural abilities dodges the obvious at every turn.

A few years ago I was lucky enough to hear film director Sally Potter use the term ‘barefoot film-making‘ to describe the way she produced and distributed her film Rage, with the aim of sidestepping the “cultural gatekeepers” and connecting directly with her audience.

While comics don’t face anything like the same barriers to production as film – indeed, their accessibility is one of the medium’s strengths – I still feel that same thrill of energy when I encounter the work of an artist who takes the whole chain of production and distribution into their own hands.

It was Michel Fiffe’s Copra that first put the phrase ‘barefoot comics’ in my head, but it applies equally to Towerkind, a 13-part series of mini-comics by Toronto-based artist Katherine Verhoeven.

It was Michel Fiffe’s Copra that first put the phrase ‘barefoot comics’ in my head, but it applies equally to Towerkind, a 13-part series of mini-comics by Toronto-based artist Katherine Verhoeven.

Reaching 160 pages, Towerkind is an oblique end-of-the-world story, seen through the eyes of a diverse group of children in the city’s St James Town high-rise housing project – apparently the most densely populated urban community in Canada.

The kids we focus on have become aware of an impending catastrophe through a number of supernatural abilities, but the comic’s execution is as far as possible from the wide-screen Hollywood spectacular you might expect from that high concept.

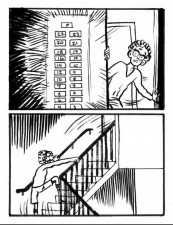

Instead, each episode is an elliptical little snapshot, focussing on character and emotion rather than origin stories and TV newsreader info-dumps. And while that kind of narrative economy won’t be for everyone, it leaves room for the reader to fill in the gaps and creates an almost palpable sense of claustrophobia and foreboding.

Instead, each episode is an elliptical little snapshot, focussing on character and emotion rather than origin stories and TV newsreader info-dumps. And while that kind of narrative economy won’t be for everyone, it leaves room for the reader to fill in the gaps and creates an almost palpable sense of claustrophobia and foreboding.

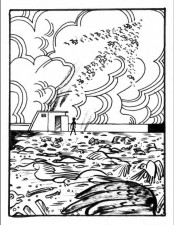

The pace picks from about the midway point, but even in the climactic chapters, as society around them starts to crumble and the children’s destiny becomes increasingly uncertain, the comic retains its distinctive intimate and slightly dreamlike atmosphere.

And, in another sign of Verhoeven’s narrative originality, the story ends exactly at the point where Hollywood would leap into Act II.

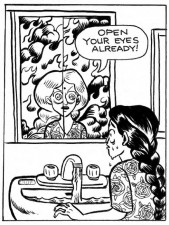

What Verhoeven evokes most vividly is the unease and confusion of childhood, and the sense of having to grow up quickly and deal with an adult level of responsibility. When things start to fall apart, it’s the kids who have to take their survival into their own hands.

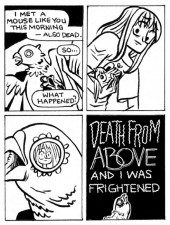

Her no-frills, decisive cartooning helps to create some deft characterisation, from Tyson, the self-proclaimed ‘king’ of the project’s kids, who almost vibrates with angry energy, to the deeply sensitive Mackenzie, who can communicate with recently deceased animals, and the visionary Maha, who sees the impending disaster of ‘Fire from above’ in the bubbles she blows, but can’t do anything to stop it. The other main characters are equally well delineated, creating a strong emotional impact from a few brief appearances.

Verhoeven also uses the mini-comic format well. Each of the tiny issues (around A6/15×11 cm) has a nicely designed wraparound cover, and there’s something very pleasing about the way the bundle of issues sits together – the sort of thing that’s like catnip to the seasoned comic reader/collector!

Possibly the most striking thing about Towerkind is that the moment you finish Issue Thirteen, you want to go straight back to the beginning and start again. And there aren’t many comics you can say that about.

All 13 issues of Towerkind are available from Kat Verhoeven’s webshop (do people still say ‘webshop’?) for $15 plus postage. Katherine also sort-of-exclusively revealed to Broken Frontier that she’ll be publishing a collected edition later in the year.

She’s a member of the Friendship Edition Collective and produces a webcomic called Meat & Bone.