Chris Lackey’s 128-page graphic novel is an intriguing and timely exploration into what life might be like in a “post-human” world.

Since crossing the pond from the US to live in Yorkshire a few years ago, writer, illustrator and designer Chris Lackey has become a dapper presence on the UK creative scene. After collaborating on jazz-horror-humour mash-up Deadbeats (published by SelfMadeHero), he took to Kickstarter last year to fund the production of his own original graphic novel – Transreality.

Lackey’s confident and stylish book tells the tale of James Watson, a family man whose life has been disrupted following a road accident. Since the crash he’s been suffering from a rare neurological condition, Capgras Syndrome, which leaves him feeling adrift in a sense of unreality – detached from the world around him, as if his loved ones have been replaced by clones.

Before long, courtesy of an overheard conversation, Chris finds that not only is there a little cluster of Capgras suffererers in the small town of Keighley, but there’s also a medical researcher, Dr Audrey Geller, who runs a support group.

If that all seems a bit of an unlikely coincidence, you’re on the right track. About 20 pages in, Lackey pulls the rug out from under both James and the reader; it’s probably not that big a spoiler to reveal that James’s everyday life isn’t quite what he thinks it is.

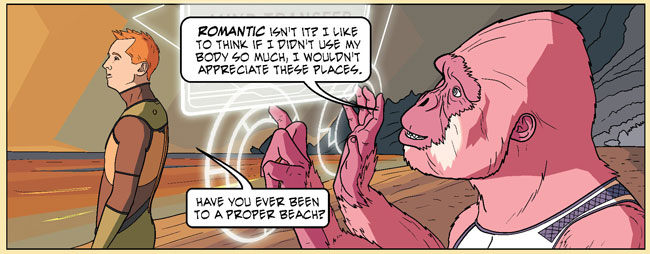

As he slips narratively and psychologically down the rabbit hole, James finds himself in what the book’s blurb describes as “a universe of splintered cultures, artificial intelligences, uplifted animals and virtual worlds”.

Fortunately, he’s quickly taken under the protective, um, wing of a charming pink gorilla named Alexis, and before long he’s up to his digital bits in a conspiracy to rescue his friend from the all-powerful conglomerate, Rainbird Industries, as well as a much more personal quest to be reunited with his wife and children.

As you might pick up from even that brief synopsis, Transreality includes a melange of familiar tropes from a particular strand of sci-fi. It’s easy to detect themes from The Matrix, Inception, the cyberdelia of Jeff Noon, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Total Recall, Neuromancer, Dennis Potter’s Cold Lazarus… But, then again, these questions over the nature of existence and perception have occupied thinkers and artists for millennia.

They’ve become considerably more pressing of late as the rush of technology forces us to consider what might be a “post-human” state. Indeed, Lackey’s book gets your noddle spinning into some interesting theoretical areas. If we’re prepared to leave our bodies behind, will it be liberating or restrictive? Who’s going to rule that environment, and with what agenda?

Might we even be there already? As far back as 1985, long before we all had hot and cold running data, academic Donna Haraway considered how much we already interacted with technology and wrote (in ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’): “We are all chimeras… fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs.”

Think of the way we outsource our memories to search engines (“distributed cognition”) and park our repositories of photos, videos and anecdotes in ‘the cloud’. We all know people who spend so much time updating their social media feeds that their bodies are arguably just there to maintain the bigger ‘hyperself’ of their online personae.

Perhaps our physical bodies are becoming just one little, peripheral node in a wider presence that exists virtually to a greater degree than it does physically. If that’s the case, to what degree do we retain our autonomy as physical beings? At what stage do we become the tail trying to wag the dog?

In the universe Lackey depicts in Transreality, the limits of the human body no longer apply; people can achieve digital immortality. Sounds great, right? Maybe not so much. Early on, a character chooses to end his life rather than persist as a digital construct: “I’m a ghost. I think I’m alive, but I’m not. I want to be put to rest.”

However, all this dizzying speculation is bundled into a story that keeps these existential questions on a very relatable human scale. By the time things get really weird, the main characters are well established; despite the protean environment depicted, their relationships and motivations remain grounded – with the result that the climax of the book is deeply moving.

That grounding is helped by the heavily modelled/photo-referenced art style (the chance to ‘star’ in the book was one of the Kickstarter rewards on offer). Drawing on his adopted home town, and cleverly reflecting one of the threads of the book, Lackey deftly creates the quotidian world that James inhabits.

And while the art style is a bit startling at first, and prone to an occasional bit of ‘over-acting’, the confidence of Lackey’s line and his bold colouring choices (showcased on some very nice paper) carry it through as the book develops. By the time we’re into the environment of shifting realities and virtual states, Lackey’s in top gear.

Over the past few months there have been some prominent comics works looking at how technology might mould our relationships (Alex+Ada, A Boy and A Girl), and Transreality can its place among the best of them. Its familiar elements are given an original and thought-provoking spin by Chris Lackey’s confident craft; if you like a bit of empathy and humanity with your futuristic speculation, then Transreality is certainly the book for you.

Chris Lackey (W/A) • Witch House Media, £10, March 2014