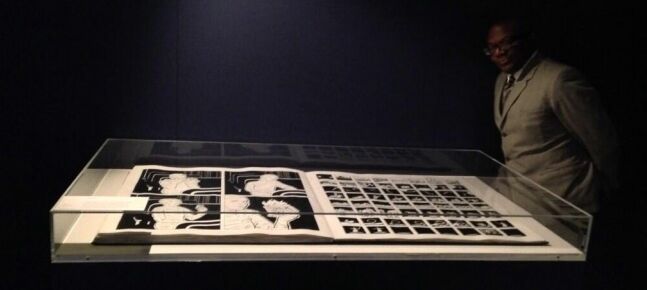

Of all the exhibits at the Comics Unmasked show – running at the British Library until August 19th this year – one of the most intriguing by far is Woodrow Phoenix’s labour of love She Lives. A one metre square, 82-page graphic novel, this astonishing undertaking is a true celebration of the potential of the form from the creator who gave us the powerful graphic journalism of Rumble Strip.

Given the sheer physicality of a project like She Lives, the opportunity to see inside its mammoth covers and experience the book as it was intended to be seen has to be specially organised, and this Friday 23rd May at 4pm Woodrow will be on hand for the first in a series of live “page turnings” in the gallery at the British Library. Ideal timing for those hoping to catch the Comics Unmasked exhibition before this Friday’s Myriad First Graphic Novel Competition event perhaps!

Below is Woodrow’s own account of the conceptualisation, design decisions and unique reading experience of She Lives. A remarkable project in an already exceptional showcase for the medium at the British Library.

***

“SHE LIVES” is a silent comics story, set in California in the late 1940s. It is a giant format book, one metre square, that tests how scale affects the reading and comprehension of a wordless narrative, and an audacious comic art experiment that has never been attempted before.

Silent comics present an interesting challenge to the reading experience. The absence of balloons and captions means there are fewer elements involved in content delivery. This should result in significantly reduced ‘visual friction’ for a reader who only has to do one kind of decoding activity rather than two or three. On the other hand, text provides a useful indicator of how long one should spend on a particular panel. The length of time it takes to read a balloon is usually the ‘duration’ of a panel. Without text there is no way to determine how much time a particular panel denotes, and therefore how much time one should spend looking at it. Different readers will have different strategies for reading silent panels, which would be fine if not for the fact that many people interpret a silent panel as having no important story content. We are used to pictures being decorative and perhaps less used to a picture having consequence or significance. A comics creator must make readers understand that the pictures do not just support the captions and speech balloons but contain and deliver as much or more information in their own right.

Silent comics present an interesting challenge to the reading experience. The absence of balloons and captions means there are fewer elements involved in content delivery. This should result in significantly reduced ‘visual friction’ for a reader who only has to do one kind of decoding activity rather than two or three. On the other hand, text provides a useful indicator of how long one should spend on a particular panel. The length of time it takes to read a balloon is usually the ‘duration’ of a panel. Without text there is no way to determine how much time a particular panel denotes, and therefore how much time one should spend looking at it. Different readers will have different strategies for reading silent panels, which would be fine if not for the fact that many people interpret a silent panel as having no important story content. We are used to pictures being decorative and perhaps less used to a picture having consequence or significance. A comics creator must make readers understand that the pictures do not just support the captions and speech balloons but contain and deliver as much or more information in their own right.

In order to hold the reader’s attention and to direct their gaze my strategy was to present them with a large surface and heavy paper that would be more difficult to skip past than a typical ‘B’ format paperback. This would have the effect of slowing the reader down and making them stay on the page longer, to look more closely at what the page contains. This forced engagement would allow them to gather more information than they would from a smaller page that would be easy to flip through quickly. A key influence in this idea was the way newspapers used to present comic strips at the beginning of the last century.

Sunday newspaper strips from the 1900s-40s like Little Nemo, Polly and Her Pals, or Krazy Kat were presented as single pages, a large surface up to half a metre tall, completely occupied by the image. The scale of these images meant that readers had to respond to them by diving into them because they dominated the readers’ visual field. This experience is not one that any modern comics reader gets to encounter much anymore. Newspapers have shrunk, books and magazines mostly stick to a small range of sizes. The internet is becoming a primary reading source for many people. The convenience and immediacy of screen-based delivery systems whether computer screens, tablets or smartphones is training readers to concentrate on a small vibrant area, which is a very different set of sensations from roaming freely over a giant field of paper. The style of reading that these electronic media encourage is an almost forensic enlarging, scrolling and tapping, the image is fragmented and literally reduced to bite-size pieces.

We talk a lot about what we are losing with the transition from paper products to the screen. The biggest change is the loss of the physical qualities of a bound book. The smell, the weight, the sound and texture of the pages beneath your fingers, the way light reflects off the surface of the page. These sensations are all part of the reading experience and when we think about books, we are as conscious of these feelings as we are of the content that we are consuming. For a lot of people the sensory aspects of books are a vital part of reading. If electronic readers can take over the convenience aspects of consuming stories, there is still a very big gap in the reading experience to be filled in ways that engage readers physically as well as virtually. Ways that remind readers of other aspects of an experience they may be missing.

Woodrow Phoenix has crafted “She Lives” to be a surprising and absorbing visual and narrative experience. In order to make a book as giant as possible, he had to bind it himself using the largest paper size available. He then took the unprecedented step of actually drawing the story into the bound book itself, so what the reader is seeing is page after page of original comics art work, exactly as it was made, with all the corrections and marks visible. “She lives” is a narrative, an art object and a conceptual challenge all in one giant one metre square package. It is a ‘public’ display of a usually hidden kind of drawing production and a celebration of comics imagery.

Comics Unmasked runs at the British Library until August 19th.

Looking good

[…] I did miss a few things I really wanted to see; Woodrow Phoenix’ exhibition and talk on She Lives would have been spectacular (but the downside of a new car was the pre-booked MOT taking up […]