This article was originally published by Tom Whiteley on his excellent Suggested for Mature Readers blog. We are sharing it here to mark the release of the new hardback edition of Zenith: Phase III from 2000 AD.

In the toy cupboard at my mother’s house there’s a basket of die-cast metal cars that belonged to me and my brother when we were kids. Few of them have any plastic left in the windscreen. Most have staved-in roofs, as if they’d been run over by a monster truck. In fact they were smashed in with a big rock. These are the survivors; most were rendered unrecognisable in an early-adolescent production line of destruction.

That kind of acting out seems a key element in becoming an adult. It’s why teenagers smoke and drink on the swings in the park, showing the place of their childhood how grown-up they are. It explains that bondage fairy craze of a few years back, defiling icons of innocence in the trappings of adult sexuality. It’s why students speculate about their favourite kids’ TV shows being conceived under the influence of psychedelics. And it’s one of the driving forces behind revisionism in comics.

Alan Moore, in the introduction to Gaiman and McKean’s Violent Cases, uses a metaphor of comics growing up: the Golden Age as the years before seven, Marvel and the Silver Age as an eight-year-old growing into a teenager, and the sex-and-violence-obsessed thrashings of the Dark Age as the hormonal storm of adolescence.

Putting aside the depressing realisation that in the decades since, the comic industry appears to have grown up into a stereotyped comics fan, I’ve always thought the metaphor was accurate. Comics in the late 1980s and early ’90s were adolescent boys sneering at their previous selves, laughing affectedly at their childishness and smashing all their toys up with rocks.

Phase III is the boy with a rock. The toys are characters from British comics – a fool’s parade of superheroes from the UK’s long publishing history, and a universe of analogues for the characters of DC Thomson, the Scottish publishers of the Beano and Dandy.

Look them up here and marvel that, in a world of comics and the internet where every offhand panel reference in League of Extraordinary Gentlemen gets tracked down, nobody knows who Mr Lion and Mr Unicorn are.

Morrison hasn’t been as painstaking as Moore would be. Familiar characters like the Leopard of Lime Street, still being published in the ’80s, get walk-on roles. Other characters, far more obscure, get decent speaking roles. In among them are Morrison and Yeowell’s own inventions: querulous winged heroes with Ride haircuts, half-remembered stars of long-ago strips turned monstrous.

I don’t think I had any idea who any of these people were when I first read this, back in 1989. Maybe Hotspur – I think we may have once read The Hotspur when it was around , but Hotspur himself isn’t from that – and the Steel Claw perhaps had a ring of familiarity. And there’s something in the presentation of Archie that tells the reader there’s meant to be a shock of recognition.

But all the rest were new to me, and they’re still unfamiliar. I can’t tell the invented from the genuine, the analogues from the originals. I’m settled in that incomprehension. None of the older heroes plays any significant role anyway; as with any other crossover, it’s our guys who do the work.

And I didn’t make the leap from Jimmy Quick to Billy Whizz, from the Z-Riders to the Q-Bikes, because of my perspective as a 15-year-old very definitely into adult comics who’d put the Beano and the Dandy behind me. To even include nods to them would have marred the work for me.

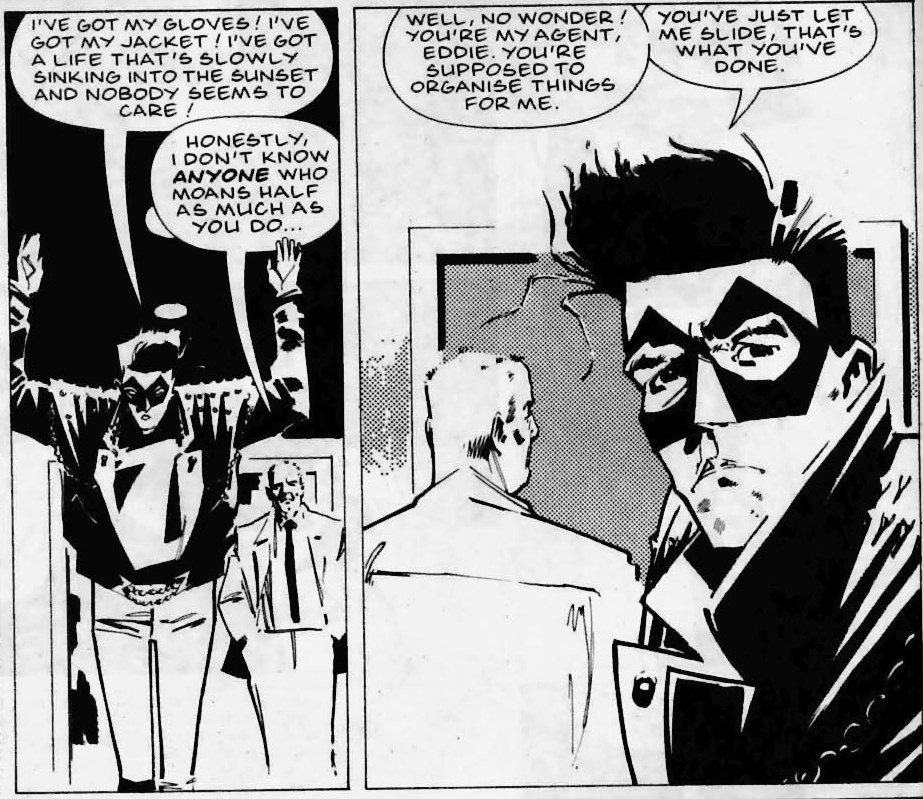

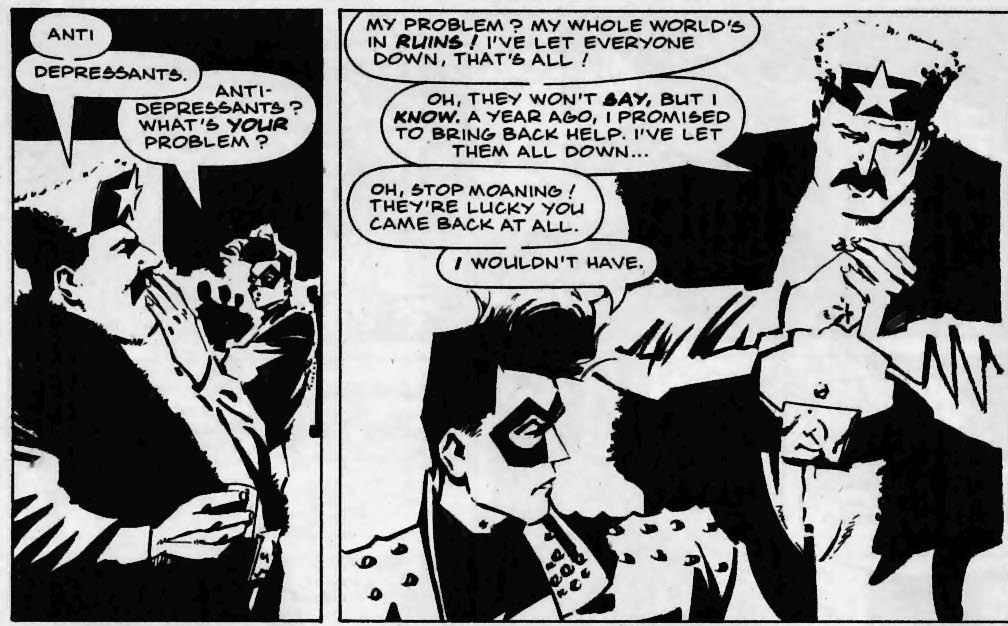

By Phase III, the template of Zenith’s storylines had become apparent. Take a standard superhero tale – attack of the super-Nazi, billionaire holds the world to ransom – and apply it to the title character, who doesn’t give a bugger. Watch the structure collapse, and insert Peter St John where it needs holding up. Drop in hints about the Plan.

Simple, effective and casually compelling. American Splendor was addictive because you couldn’t wait to see what Harvey Pekar wouldn’t do next. Zenith has the same attraction; how will the day be saved without the title character ever really bothering to understand what’s going on around him this time?

This volume, the longest continuous Zenith story, takes on a relatively recent trope of superhero fiction: the crossover. A big crossover can reduce anyone to a bit-part. Crisis On Infinite Earths, which this resembles more closely than any other, could find no significant role for Batman.

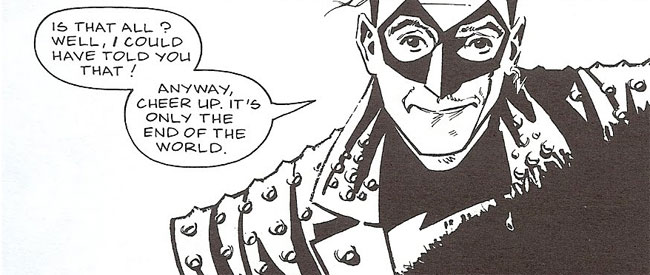

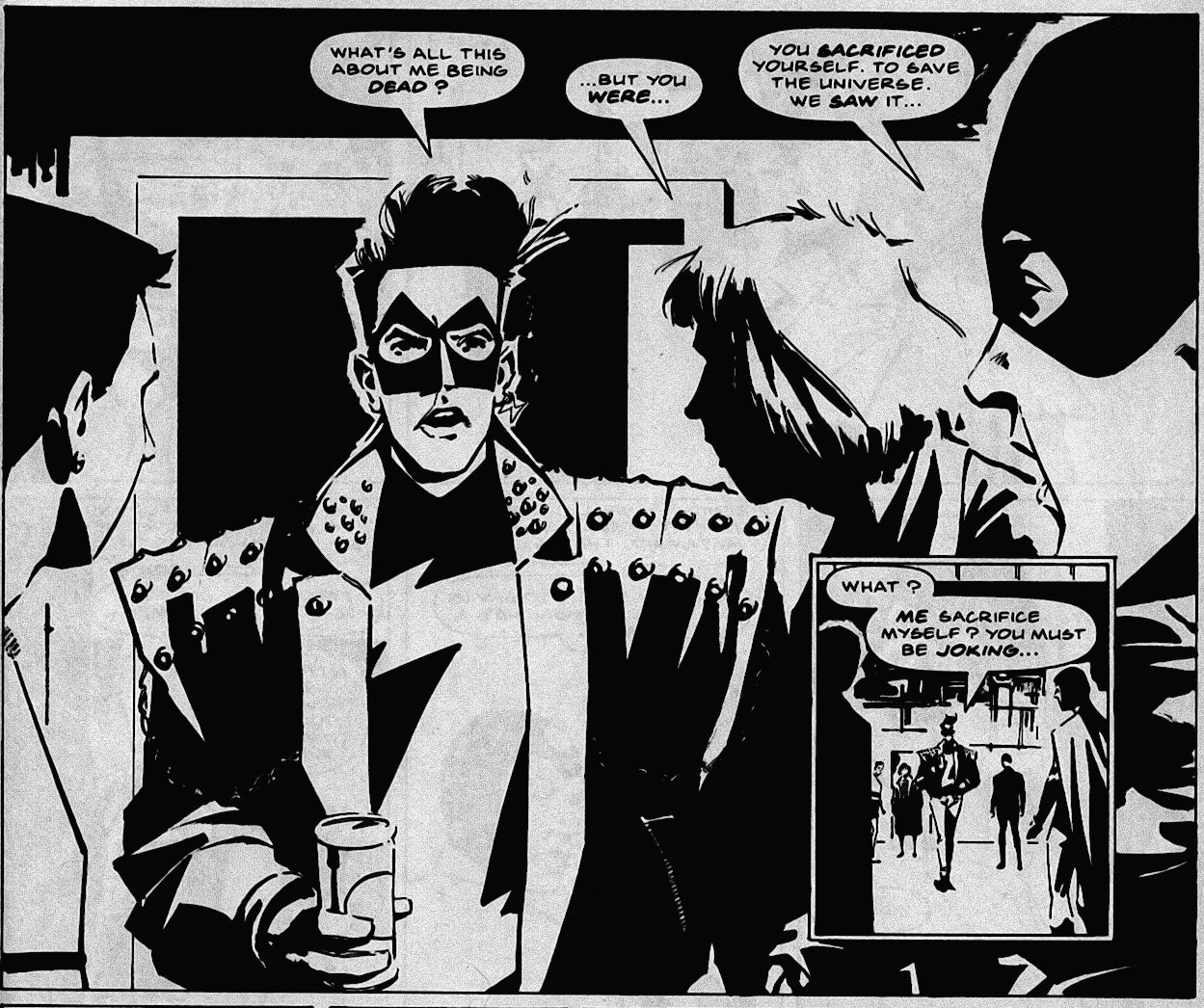

Morrison doesn’t even try to find a role for Zenith. He comes along because he’s bored and to spite his agent, acts as a mocking Greek chorus to the portentous action, and uses his superpowers exactly once during the whole thing. And that’s no great heroic action.

He doesn’t punch through a baddie or use telepathy to save the day, his minor moments of bravery from the previous books. He wrenches a train carriage out of a tunnel so he can flee, and he doesn’t even get away clean. He’s saved by a pre-op transsexual who fancies him. Not, it’s fair to say, the stuff of legend.

Following that he plays a small part in the revelation that the heroes have been set up, as a go-between, and then doesn’t even appear at the climax. He’s offstage throughout, missing presumed chilling.

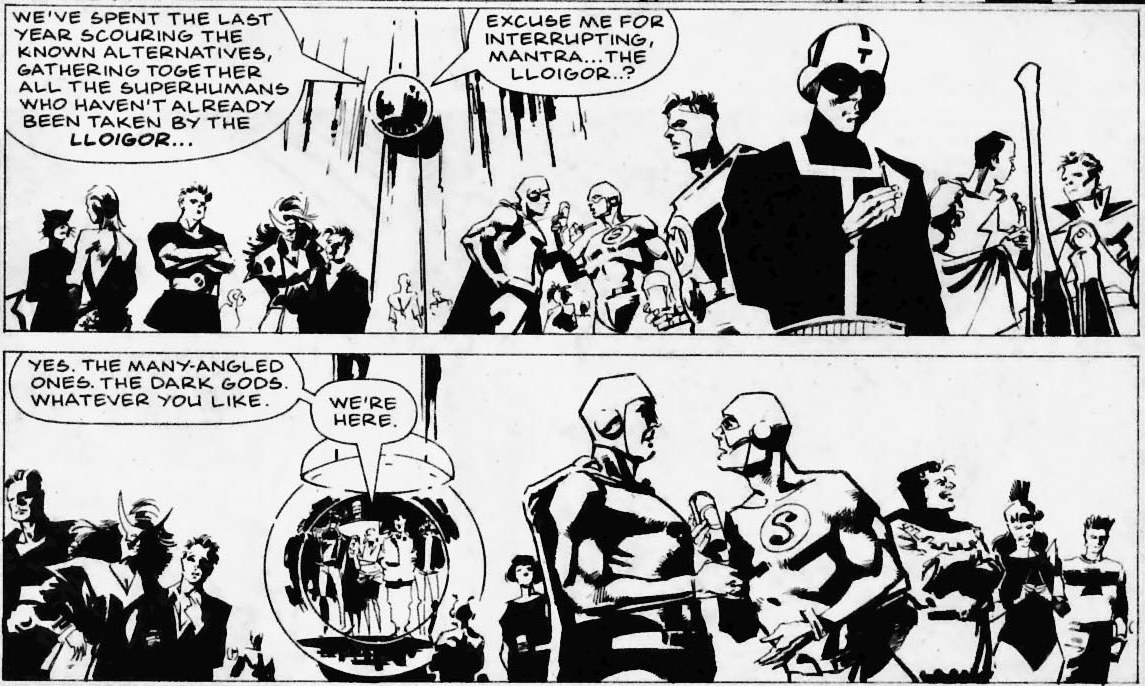

Crisis was about the heroes of many worlds, of many different publishers and eras of publication, gathering together to save their universes. In huge, painstakingly detailed crowd scenes by George Perez they listened to Alexander Luthor, a genius from a very different Earth, direct their efforts against an unearthly foe.

Phase III is about the heroes of many alternatives, some from older IPC/Fleetway comics and some analogues of British comic characters, being directed by an alternate Maximan against their Lovecraftian foe. The similarities are obvious, even if the briefing’s backdrop has more in common with the barren and easily-drawn planet of Secret Wars.

Steve Yeowell’s art takes a further step into abstract sketchiness here. Backgrounds are rare, especially in the near-empty locations where much of the talking-head stuff takes place. Jagged black edges shape the action. Drifts of Letraset dots represent the middle distance, or just fill out the composition.

What Yeowell isn’t especially good at, to a given value of good represented by the neat but incredibly detailed work of George Perez, is a superhero crowd scene. He’s struggling without colour anyway – most of what makes a costume iconic is colour in the correct combinations and proportions – and Yeowell is working with form, with shape, with shadow. That can make it difficult to show the exact chest emblem. So the assembled heroes emerge only slowly, getting names and stories over the course of the narrative rather than being instantly tagged with their histories.

This all-powerful Maximan is blind, mad, wears a blindfold and the robes of a wizard with nothing underneath (this will be important later), and totes a couple of ravens as accessories. In case the teen readership didn’t get the reference – I didn’t – he refers to himself as Oh-Dinn.

However, this seems to be a reference without a connection at the other end. Apart from the sacrifice for wisdom, which in this case takes both eyes and seems to be a dubious bargain, there’s no real resemblance to Odin, no Thor, no Loki, no Balder. It’s thrown in just to be cool.

His speech patterns are taken from Peter Stillman, the man raised like Kaspar Hauser in a single dark room in City of Glass, the best-known story in Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy. Compare the two: the first is Stillman, the second Maximan.

“I am Peter Stillman. That is not my real name. My real name is Peter Rabbit. In the winter I am Mr White, in the summer I am Mr Green. Think what you like of this. I say it of my own free will. Wimble click crumblechaw beloo. It is beautiful, is it not? I make up words like this all the time. That can’t be helped.”

“Seeing you all here reminds me of air breathing on the janglechimes when all was snug and babytight and… These words escape so easily from behind my cage of teeth. Yes.”

But in 1989 it wasn’t thought that a black-and-white story in 2000 AD would be remembered and compared to the fictional source that it stole from. Plagiarism was barely plagiarism then. And the Maximan sequences are compelling, actually losing some of their power when the speech becomes narration over flashback.

What happens? Well, it’s a mess like all crossovers are. There’s a briefing which explains that for cosmic reasons – no questions please, cosmic forces at work – the heroes must visit two alternatives taken over by the Lloigor and destroy them. The best bits, apart from Zenith’s complete evasion of responsibility and talent for saying exactly the wrong thing, are the bits where the kid hits the cars with the rock.

We saw Alternate 666, a wasteland of dead and dying Beano characters, in the first episode, and we quickly return to it. Morrison’s happy to make it clear exactly what he’s doing by showing us a concentration camp in Disneyland, really putting that metaphor out front.

But there’s a real heart to the place, this landscape of starkly-drawn horrors, the elegant desperation and cowardice of Prince Mamba sneaking through the ruins, the quiet anticipation on Miss Wonderstarr’s face as she waits to surprise him. Tiger Tom and Tammy, apparently analogues of Billy the Cat and Katie, hide sick in their basement, desperate for food, medicine, help.

It’s the post-apocalypse London of Miracleman expanded across the whole country, even with a body on a weathervane. But even though we’ve seen it all before, there’s a breezy freshness to it, to the way it’s told. It helps that Morrison’s never entirely serious, otherwise he wouldn’t have thrown a clown like Zenith into the mix; it helps that Yeowell only shows us the sharp edges and shadows of the horror.

By the time we’re in Alternate 257, where St John and Mantra are leading the fight, we’ve missed most of the action. Very little of the world is shown, just a couple of wasteland clashes between heroes, but Hotspur’s Christian rallying march and the insouciance with which Mr Lion and Mr Unicorn cut it down is lovely.

The fact that it’s such a confused disaster is almost reassuring; in all those other crossovers, the heroes all knew what was going on. But in reality a multi-universe struggle co-ordinating a bunch of people who’d only met the day before would be as confused and scattered as a stag night.

Mantra, who’s been given more time to introduce herself than anyone, gets killed by Maximan in a sudden flash of bloody violence. St John, as in Phase I, proves the saving of everybody. Zenith gets a death scene and a glorious, hilarious resurrection. He delivers the punchline.

Apart from the ruthless glimpses we see of the former Cloud 9 members, with David and Ruby both killing without qualm, little happens to advance the plot of the Plan. But to anyone familiar with the trappings of superhero crossovers, with post-apocalyptica or with the stars of British comics past, ‘Phase III’ is a romp grinning and grim, violent and silly, ridiculously serious and seriously ridiculous.

Grant Morrison (W), Steve Yeowell (A) • 2000 AD/Rebellion, £20, April 2015