The easiest way to describe a kōan — a Japanese reading of the Chinese gong’an — is to compare it to our version of a riddle, although Zen Buddhists probably won’t describe it as such. They have long used kōans as part of meditation techniques, to help unravel truths about themselves and the world. In fact, they may simply choose not to describe a kōan at all.

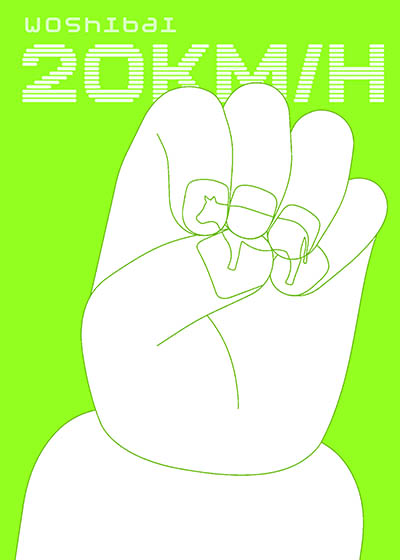

This may also explain Chinese artist Woshibai’s approach. Born and raised in Shanghai, his work attracts thousands of likes and comments on Instagram, where a little over 72,000 followers engage with his minimalist art that says a lot without the artist himself saying anything at all. That approach also characterises 20 km/h, his debut for Drawn & Quarterly, comprising stories that combine observational humour with a sharp, poetic sensibility. There is humour here, and pathos, and a quiet nudging of attention to the magic that lies around us if we stop to look.

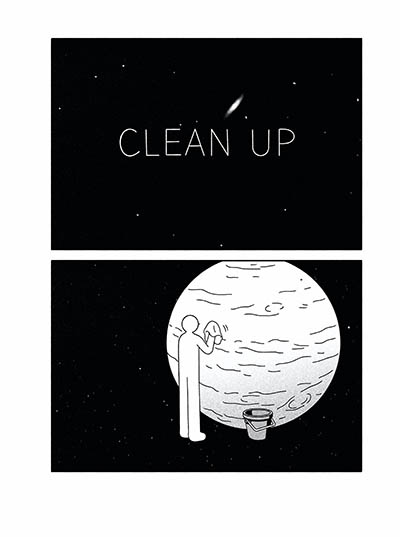

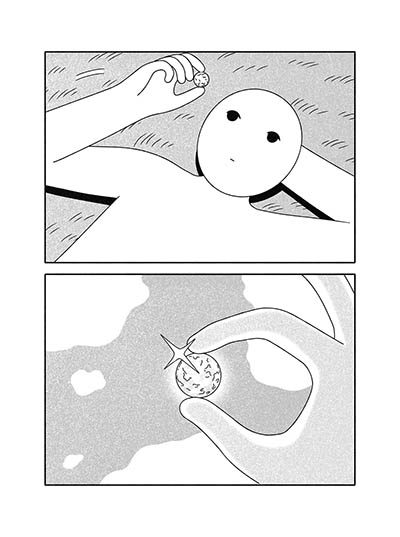

There are a few parallels that come to mind as one goes through these pages. Richard McGuire’s Sequential Drawings, for instance, where surprising stories unfold with images that are also deceptively modest. Like McGuire, Woshibai’s lines are clean, and his panels uncluttered. There is also that attention to detail, a reward for those who can take things slow and focus on the little things. It also brings legendary Saul Steinberg’s The Labyrinth to mind. Having said that, it may be unfair to draw these parallels or use them as references, given the unique space Woshibai occupies.

Describing his working style in an interview not long ago, he spoke of how a picture, sentence, or even something spotted on the road had the potential to attract his attention and take him down to some other place. It feels like an exploration, a teasing out of meaning that first occupies the artist, then inevitably compels a reader to do the same.

An interesting thing about Woshibai’s stories is how impossible they are to describe. One can paraphrase his panels, of course, but never do justice to how they trigger layers of meaning with each reading. They almost work like visual aids to the kind of tests long administered by Zen masters to students, like the question ‘What is Buddha?’ which is answered by something like ‘Three pounds of flax.’ There may be a bit of head-scratching there, but it slowly gives way to some semblance of meaning, a glimpse into the profundity that lies at the heart of human existence.

Take the story that gives this collection its title: it is a wordless set of panels depicting a chariot drawn by butterflies. That is all there is, but the images linger, along with a feeling that this is entirely plausible, while being far-fetched. The mind and heart say two different things. It is the kind of picture that lingers, long after the book has been put away.

Maybe that is precisely the point. Consider one of the more common kōans used by Chinese priests in the 12th century: ‘When both hands are clapped, a sound is produced; listen to the sound of one hand clapping.’ It could function as Woshibai’s artistic statement of intent: Perhaps all he wants us to hear is the sound of one hand clapping?

Woshibai (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $29.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira