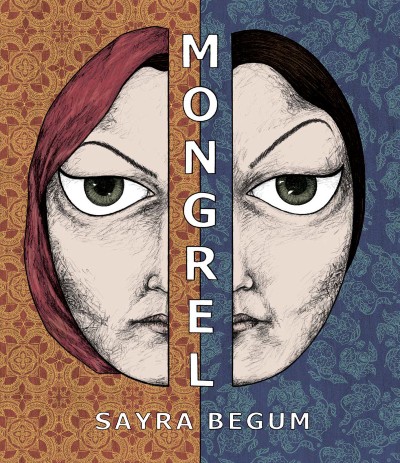

One of a crop of outstanding British first-time graphic novels to hit the shelves in 2020, Mongrel by Sayra Begum incorporates autobiographical elements elements to tell the story of Shuna, a young British Muslim woman caught between the pull of two worlds. Published by the acclaimed British publisher Knockabout it’s a book we called “an impressive and assured debut” when we reviewed it here last summer. I caught up with Sayra (above) to chat about the influence of Islamic art on her practice, her distinctive visual style, and the particular responsibilities of autobio-based work…

ANDY OLIVER: To begin with can you introduce yourself and tell us about your wider artistic background and practice?

SAYRA BEGUM: Islamic miniatures and Surrealism are my key influences. It was about 11 years ago when I first started looking deeply at Islamic art beyond the pictures of mosques and calligraphy that were hung in my family home. My work always seems to gravitate around religion, culture, and human nature, and over the past few years I’ve become increasingly conscious of our relationship with the environment as well as each other.

SAYRA BEGUM: Islamic miniatures and Surrealism are my key influences. It was about 11 years ago when I first started looking deeply at Islamic art beyond the pictures of mosques and calligraphy that were hung in my family home. My work always seems to gravitate around religion, culture, and human nature, and over the past few years I’ve become increasingly conscious of our relationship with the environment as well as each other.

Last year I released my first graphic novel, Mongrel. It was a project I started whilst I was a student at Falmouth University (2014 – 2016) and it remained at the centre of my creative practice until its completion in 2020. I poured everything into that book for a pretty long time.

I recently returned to Falmouth to work towards my PGCHE (Postgraduate Certificate in Higher Education) and I am tutoring on the online MA Illustration course. At present I’m based in Nottingham, although I’m getting the itch to move again. I’m working on a short comic for the 10 Years To Save the World digital anthology. Last year I was due to do the Comics Cultural Exchange Residency in Prague, but it was cancelled due to obvious reasons, so we are hoping to reschedule for this year..

AO: Your first graphic novel Mongrel was released last summer. We called it “an impressive and assured debut work from a new voice with a keen understanding of the singular opportunities and intricacies of comics narrative” when we reviewed it here at Broken Frontier. Can you describe the premise and themes of the book?

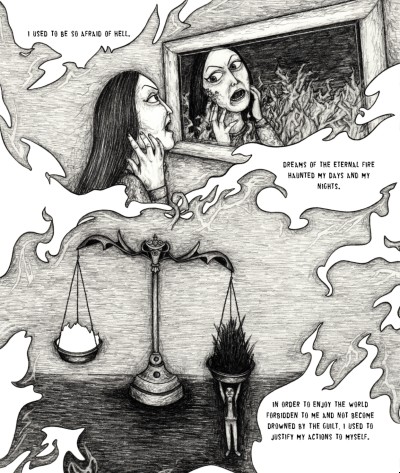

BEGUM: I used to be afraid of being personal in my work. I would express myself by projecting whatever it is I’m witnessing, feeling and experiencing onto a fantastical fictional world. Something changed when I discovered autobio comics. It was Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Craig Thompson’s Blankets which really opened a whole new world for me. Whilst I was studying at Falmouth, I focused on researching autobio comics and autobio theory in general. Paul Gravett, Bart Beaty, Hillary Chute and Max Saunders – to name a few influential authors. I then spent months developing my style, experimenting with different mediums and techniques, which led to the aesthetics of Mongrel.

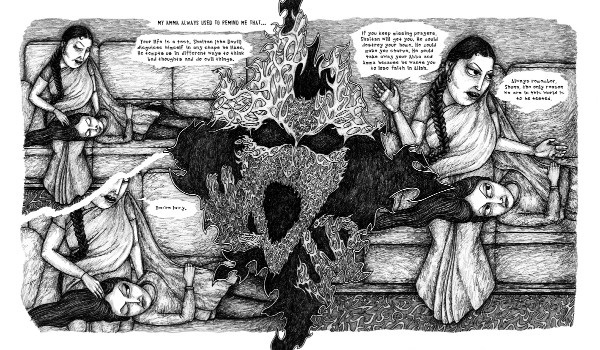

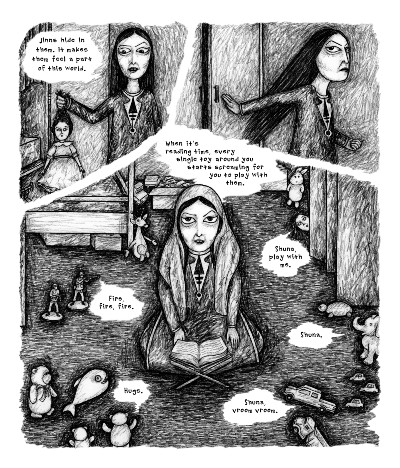

That’s a brief insight into the journey, so to the book itself: I have as honestly as possible recreated my memories of growing up in a traditional Muslim household in South West England. Shuna is my alter-ego. She faces challenges that are quite typical for a young Muslim girl. She wants to be a good Muslim, she wants to make her parents proud, yet she also seeks adventure and feels the need to fit in with her peers. Some of Shuna’s memories are atypical, as she is a mixed-race child, the daughter of a Muslim convert. Shuna learns to switch back and forth from her rebellious face to her pious one depending on her company. This becomes more difficult when she falls in love with a non-Muslim.

AO: How did your association with publisher Knockabout come about?

BEGUM: I had a couple of Knockabout books on my bookshelf, Brick’s Depresso and Paco Roca’s Wrinkles, and of course, I was familiar with Alan Moore’s From Hell. I thought I’d reach out to them as I could tell from their collection of published books that they were open-minded about different genres and styles. So, I found Knockabout’s email and introduced myself and my work. Tony Bennett (founder of Knockabout) invited me to have dinner with him and his colleague. I had the entire book scripted at this point, but went full steam ahead trying to get as many pages as I could down as roughs. With most of the pages containing roughs, I printed, bound a dummy book and took it with me to dinner in December 2017.

AO: As mentioned, Mongrel fuses autobiography with a cast of fictional avatars. Why did you adopt that approach to the story? And on a related note, what are the particular challenges and responsibilities involved with autobio work? How did you have to adapt your story in relation to them?

BEGUM: I was conscious of the subjectivity of our memories. Our own memories represent our own truth, but they do not represent the truth of those others contained within them. Although my long-term memory is pretty good, I remember things that my brothers have forgotten or things which they have hidden in the back of their minds. But memory is still unreliable, even if you have good long-term memory, our memories fade and become distorted, and sometimes we replace the fade with imagination.

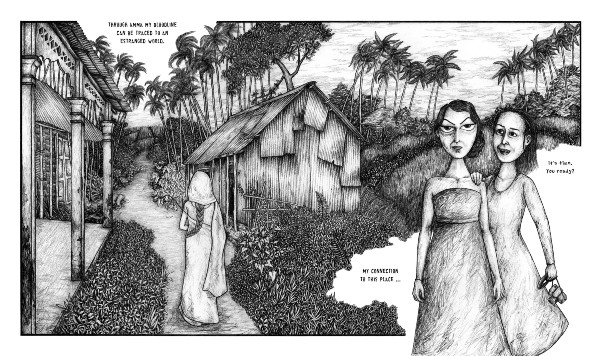

Drawing my world in a warped, out-of-proportion style, highlights the subjectivity of the familial history I share. I am the one interpreting and analysing. Although I could never truly see through someone else’s eyes, I needed to try and walk in their shoes. Fictional avatars are a way for me to create distance between reality and its cartoon reflection. The distance allows for a more critical and objective analysis with the removal of sentimentality attached to the conversations, the arguments and displays of affection. I needed this detachment to really understand the characters and in turn, communicate three-dimensional people. I had a responsibility to do this as our identities are complicated. It’s way too easy to contribute someone’s attributes and actions to one root cause. For instance, when I hear remarks implying that someone is austere, violent or suppressed because they are a Muslim, it highlights the convenience of blaming the so-called usual cause, rather than considering the complexity of our lives and identity. There are many reasons why we end up forming the personalities we have and make the choices we do.

AO: In terms of reactions to Mongrel over the last few months, what has been the most rewarding feedback you’ve had to it?

BEGUM: The most rewarding feedback for me is when people tell me something within Mongrel resonated with them, bringing forgotten memories to life. I’ve connected with so many other second-generation Muslims as they opened up to me about their experiences. One reader told me that her upbringing was nothing like mine, that hers was very liberal and she did not experience the control and rigidity that I did, but she respected this was my story to tell. We spoke about the factors which could contribute to our very different experiences, the age of our parents when migrating and living in a city compared to a rural upbringing.

AO: Let’s turn to your creative process. What mediums do you work in?

BEGUM: My process is pretty simple. I use mechanical pencils, scan the drawing in and then clean up in Photoshop before dropping it into InDesign.

AO: Your visual style on Mongrel is very distinctive. What are the greatest influences on, and inspirations for, your artistic approach on the book?

BEGUM: If you don’t mind some repetition, when I was developing the style of Mongrel, I was looking closely at Islamic miniatures. I really like the proportion of the figures, how sometimes their body parts seem to awkwardly fit together as well as the broken perspective. For me, these figures represent daringness. As a Muslim child, I was not allowed to hang any pictures of animals or humans on my wall. When I discovered miniatures, I realised that these figures could exist within the pages of a book because the viewer could choose if and when they would view them. I’ve also always been drawn to surrealist art because of the constant state of transformation that we witness in the dream world.

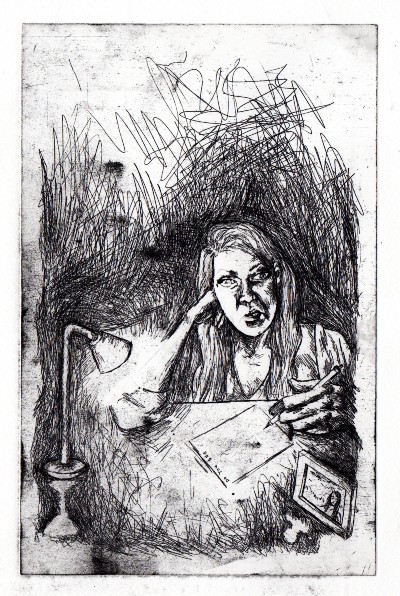

I was experimenting in the print room and ended up creating a very scratchy etching (below). I really liked this quality about it, so I started incorporating it into the way I draw.

AO: Something that really strikes the reader about Mongrel is the way in which you play with the narrative tools of the form. The shifts from sequential page structures to more expressive, freeform page compositions; the deliberate obscuring of dialogue; and a blank-faced major character to give a few examples. Can you tell us a little about how you sought to use the language of comics to further the themes and atmosphere of the book?

BEGUM: There is an in-betweenness about the medium which Elisabeth El Refaie talks about in Autobiographical Comics: Life Writing in Pictures. I felt that my in-betweenness, my story, could be used as a vehicle for readers to explore what they consider to be the ‘other’, no matter which half of my dual identity they consider to be the other.

When I was reading a lot of graphic memoirs by women it struck me how writers created a sense of intimacy and an emotional connection with readers. Creators such as Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Lynda Barry and Phoebe Gloeckner come to mind. This is because they not only tell us about their memories, but they show us, rendering their world in great detail. Images not only create this intimacy, but they highlight the subjectivity of the images being shared. The subjectivity of the images is anchored by the objectivity of the text (although this is perhaps a subjective statement in itself). When I obscured text in Mongrel, I felt it broke the tendency we have to rely on the text to shed light on the image as well as commentating my right to share another person’s story. Although our stories are intertwined with those that surround us, at what point do you stop being the protagonist and become the minor character in someone else’s story. The obscured text was a way for me to stop the sharing because this was not my story to tell.

AO: This last year has been a challenging one to say the least. As a debut graphic novelist how have you had to adapt to getting the word out there about the book in a year when launches, signings and festivals were no longer a “real world” option?

BEGUM: I’m not the most active person on social media, but I’ve really appreciated the support on there as well as discovering great creators. I’ve made a few appearances talking about Mongrel on BBC radio Nottingham, Islam Channel, Laydeez Do Comics and Comics Grinder. When the real world is open again, I hope to do those things that I missed out on, such as book signings and festivals.

AO: And, finally, what’s next for Sayra Begum? Have you started planning your next comics project yet?

BEGUM: I have! To be honest I am one of those creators that have too many ideas and not enough hours in the day to pursue them. My next book, if I can get it off the ground, will be a biography of my grandparents. Their story is very poignant and contains the supernatural. After this book, I’m thinking about graphic journalism, documenting various pilgrimages from different faiths, including Hajj from my own. But perhaps this is thinking too far in advance and I should just focus on one book at a time.

Follow Sayra Begum on Instagram here

Mongrel is available from Gosh! Comics here

Interview by Andy Oliver

[…] éléments autobiographiques de la vie de l’auteure, Sayra Begum (cf cette très intéressante interview), brosse le portrait d’une jeune musulmane, Shuna, tiraillée entre deux univers. Il y a d’une […]