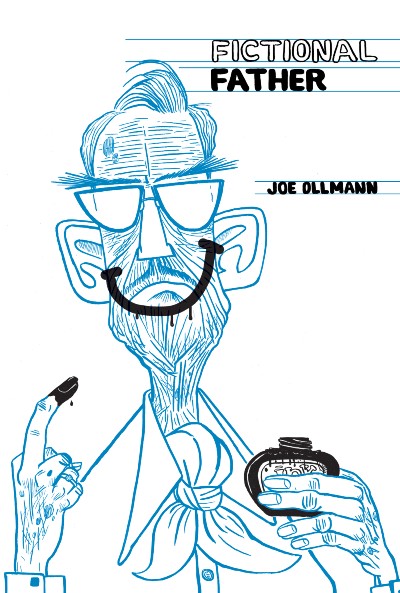

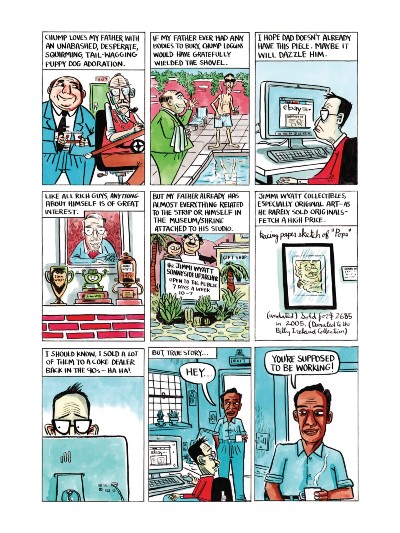

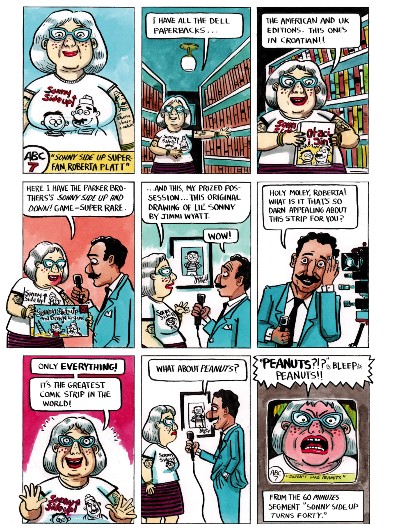

Fictional Father, by legendary Canadian cartoonist Joe Ollmann, declares its intention at the outset, its ingenious cover image pointing to what lies within. This is a faux memoir, supposedly written by a mediocre cartoonist named Caleb Wyatt, about his legendary cartoonist father. The shadow of Jimmi Wyatt looms large over Caleb’s life, as he struggles to find his identity while grappling with an indifferent mother, patient boyfriend, and a history of addiction.

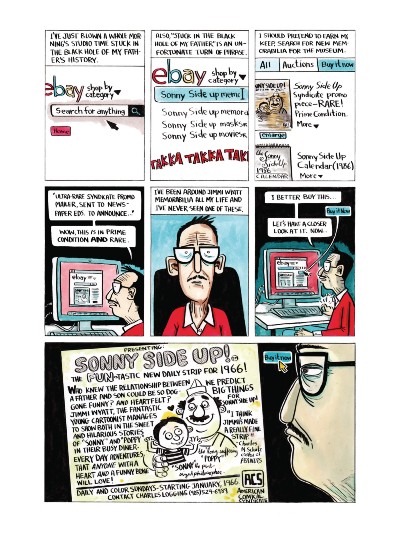

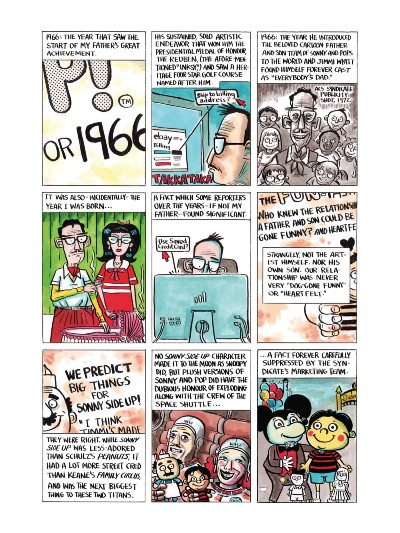

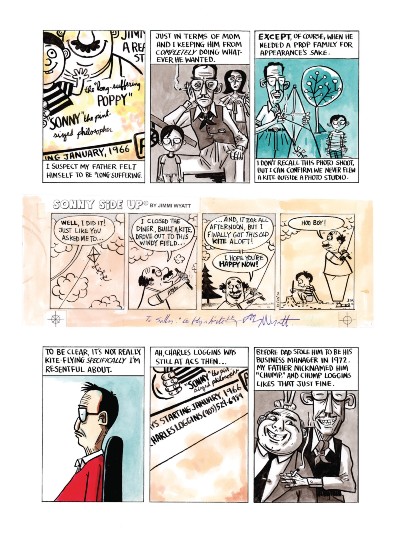

Running through it all is his father’s successful newspaper strip about a fictional father and son that has always been at odds with Jimmi and Caleb’s relationship.

Running through it all is his father’s successful newspaper strip about a fictional father and son that has always been at odds with Jimmi and Caleb’s relationship.

There are in-jokes here, cameos from other famous cartoonists, biographical details, and some revealing snippets about their own failings as fathers or sons. Ollmann renders the poignancy and complicated nature of these relationships in devastating detail, using unusual colours that he has an interesting explanation for. He doesn’t shy away from big emotions, laying bare the insecurities that lie in wait for every artist standing before a block of marble, waiting to see what it holds and whether it will reveal it secrets.

A funny, acerbic, beautifully illustrated book, it is hard to put down. We had a few questions for Ollmann about its genesis and what he hoped to accomplish. Here are his responses:

BROKEN FRONTIER: It has been almost four decades since your work began to be published. Has the way you approach a new project changed, given how audiences for comics as an art form have evolved since the time of newspaper strips?

JOE OLLMANN: In terms of approach nothing has really changed that drastically. In execution, I consciously try to be as low-fi as possible. In earlier books, I used Photoshop for colouring and tone and even (shudder) for motion blurs. I was fairly up on technology as an art director and designer, but made a conscious decision at some point to not try and make comics with computers. With my books, I try to make everything but the UPC code drawn and lettered by hand. I know other people are drawing with tablets and it looks organic and natural, but that train has left the station for me.

I guess the biggest change from the beginning was just making whatever you feel like with no thought of where it might be published. There is a purity to making a bunch of comics just because you feel fired up, without thinking what you’ll do with it. I guess I transitioned to making full length graphic novels with my book Midlife as it seemed like an easier sell and I was slowly moving to longer stories in my previous books so it wasn’t too forced.

BF: Is it accurate to describe your undeniably complex characters as somehow marked by a deep sense of tragedy?

OLLMANN: I think that’s accurate, but I think all of us are marked by some kind of tragedy however small that kind of defines us? As with artists, our limitations become our style, so it is with all of us that our tragedies make our person for good or bad. I often think that some of the most real people I know, people who really get things, have been through the shit in some way, you know? Like they operate at a different level of compassion and understanding due to their experience.

The characters in Fictional Father are super privileged people, but they still have their problems. I tried to make Cal acknowledge that fortunate position so his complaining isn’t completely intolerable.

BF: Was there any specific reason why you chose the format of a quasi-memoir to explore this relationship between father and son?

OLLMANN: I had a great relationship with my dear old Dad, especially in our later years, we had a real understanding and appreciation of each other, and I miss him every day, so the relationship in the story has no bearing at all on my own experience. You know, as I get older, I really rely on the inner voice that tells me what I’m going to work on next. Who knows where ideas come from? I just let things happen. At some point I knew I was doing a comic about a cartoonist; the father-son thing came later. It must have registered at some level that there were real life parallels in the cartooning world, but not really until other cartoonists started pointing it out. But anyone who is pumped up as representing some attribute in their art will inevitably not meet that mark in real life. Whether it’s a cartoonist drawing a close father and son relationship and being a terrible dad, or a film director like Elia Kazan having a strong moral voice in his work and ratting out his commie friends to the McCarthy senate hearings.

BF: You have described yourself as a rural child, and I was wondering if that kind of background lends itself to paying more attention to the inner lives of people than if one were to grow up in a city. The work of your contemporary Seth comes to mind too, with regards to this question.

OLLMANN: I grew up in the country, the youngest of six kids with four years between myself and the next closest sibling, so I spent a lot of time amusing myself. I was left to my own devices a lot. I don’t know if that made me more observant or anything, but it definitely led me to drawing all the time to entertain myself. I can remember wandering around the woods creating narratives in my weird little head. We all do that as kids, but us creative types just don’t stop when they grow up.

BF: Working on the biography of William B. Seabrook involved research for over a decade. Was Fictional Father a less painful process?

OLLMANN: The comparative ease of fiction compared to the restraints and technical concerns of non-fiction was a welcome thing for sure. It was nice to let the story go wherever you felt like and not be tied down to a narrative that already existed. Though, even in non-fiction, the author’s bias will affect the story in subtle ways by what they suppress, by what they choose to highlight. The experience of researching a real-life figure was helpful in making Fictional Father in a way, as I was able to crib the tone of promotional photos and articles about Seabrook to create faux historical documentation of fictional cartoonist Jimmi Wyatt’s life.

BF: Your use of colour is very distinctive, in the sense that your panels rarely go for pastels or tones more commonly seen in comics. Why do you choose to work with this specific palette?

OLLMANN: Ah! I am literally colour blind! I don’t know what I’m doing, I follow instinct and basic colour mixing theory. I’ve spent thirty-plus years working in print and design and hiding the fact that I’m severely colour blind. It was often like being an editor who doesn’t know how to read. I found tricks to prompt other people to name colours out loud, like hesitating and someone jumps in to finish my sentence, naming the colour. I discovered I could discern colours better under lightbulbs than fluorescent lighting, so I’d take print samples into the bathroom to look at them.

There was a Japanese software I’d keep hidden on my desktop that when you run a cursor over an image it names the colours, i. e. greenish-yellow, dark blue-grey. That was a lifesaver in later years. I always kept this a secret, but I only do occasional freelance design work now and I was doing my first book in colour and thought I’d just say out loud; I’m a colour-blind artist. Tom Devlin at D&Q is also colour-blind, and the brilliant illustrator/cartoonist Roman Murodov shouted out he also is colour-blind. My approach in painting Fictional Father was using opaque coloured inks, starting with the primary colours and then, knowing what makes orange, mixing that and hoping it approximates something like orange on the page.

BF: Not long ago, you had an appreciative comment to make about the work of Andrei Tarkovsky, and I was wondering if there were artists working in other forms who may have had an influence on your style.

OLLMANN: I guess everything we read/watch/listen to affects our work in a way. Not so much in a technical sense, but in a moral sense? Artists I love that affect my moral sense would be maybe Orson Welles, Charles Dickens, Charles Schulz, George Gissing, Karl Marx, Victor Hugo, but the single biggest influence on my writing in comics would be the work of Lynda Barry. I know I’m no Lynda Barry!! But the kindness, humanity and deep understanding of joy and pain in her work was always a revelation to me. I’m so glad that she is being recognized these days for her brilliance.

BF: One of the things I loved about Fictional Father was how deeply flawed, yet somehow universal, this relationship was. What are your personal views on the notion that parenting is an exercise often doomed to failure?

OLLMANN: Parenting is always doomed to failure at some level, but I think you can minimize the damage by treating kids with respect and recognizing their autonomy. I really hate the brand of parenting that doesn’t explain reasons for things, but lays down edicts that must be followed without question. “Because I said so,” has to be the lamest response to a child’s question. If you can’t explain your reasons better, then you don’t have the moral authority to tell someone what to do, in my opinion. I would argue further that this method of bullying parenting creates citizens who don’t question authority and respond well to the bullying of capitalism, cops and teachers.

But yeah, as a parent, sometimes you’re in the middle of bungling some interaction with your kid and you’re thinking, this will scar them, this’ll probably come up in therapy some day. It’s inevitable, but with a conscious effort and respect, you can also minimize the damage you do.

Also available from Gosh! Comics here

Interview by Lindsay Pereira