The Chinese artist Ai Weiwei was once asked a series of questions by other artists from around the world, one of which came from German photographer Wolfgang Tillmans: ‘In free societies, people often have the romantic feeling that better art is produced in circumstances of hardship. What would you say to that?’ Weiwei’s response wasn’t exactly circumspect. He acknowledged that the question was tricky and maintained that “many bad artworks have come from circumstances of hardship. But hardship can also be defined as a long period of mental and intellectual struggle.”

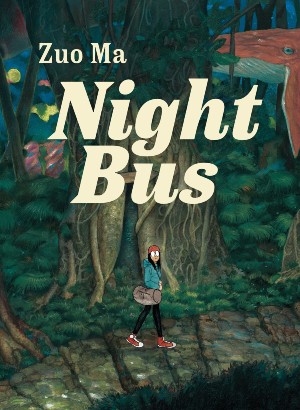

It is disingenuous and possibly dangerous to ascribe a particular set of beliefs to any work of art, be it a painting, film, or even a graphic novel. And yet, this reviewer found himself repeatedly thinking about Weiwei’s words while reading Zuo Ma’s hallucinatory debut comic. Night Bus is described as a blend of autobiography, horror and fantasy, all of which go towards the creation of a surreal world. It constantly makes one think about what lies behind this illusory façade though.

It is disingenuous and possibly dangerous to ascribe a particular set of beliefs to any work of art, be it a painting, film, or even a graphic novel. And yet, this reviewer found himself repeatedly thinking about Weiwei’s words while reading Zuo Ma’s hallucinatory debut comic. Night Bus is described as a blend of autobiography, horror and fantasy, all of which go towards the creation of a surreal world. It constantly makes one think about what lies behind this illusory façade though.

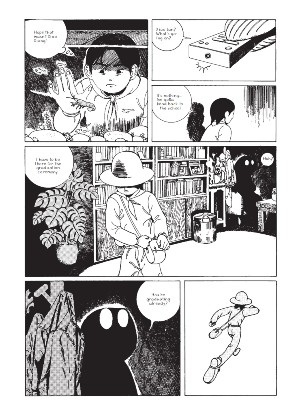

There were always distinct reasons for the emergence of surrealism, as one traces its beginnings in the early 1900s from the paintings of de Chirico and Dali to the influence of Freud and the constant spectre of war. What those artists were trying to do was make sense of the unnatural world they found themselves in, where nothing was what it appeared to be. Confronted with long-established rules that had begun to crumble, they responded the only way they knew how, making up realms of their own as they went along. It is one way of examining what Ma (the name Zou Jian goes by) does.

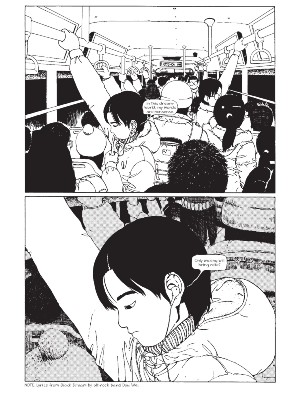

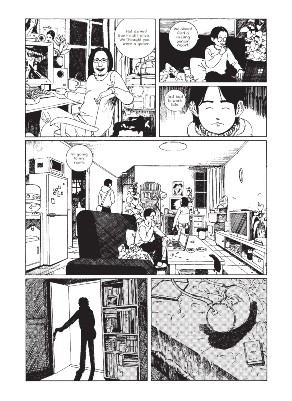

Night Bus is less a single tale than a collection of stories strung together by a narrative involving a young woman and her journey home. What should be an uneventful ride takes an unplanned left turn, going through twists and turns engendered by her fellow passengers. It is a fairly common trope among travel literature that allows a protagonist to live vicariously through the lives and ideas of fellow travellers. What is presented here, however, is anything but ordinary, because the young woman’s co-passengers accompany her through fantastical dreamscapes that slowly reveal a more personal story. At the heart of it lies the author’s relationship with his grandmother—as the epilogue poignantly explains—and her struggle with dementia. It teaches us slowly, almost imperceptibly, to look at that young woman’s journey a little differently.

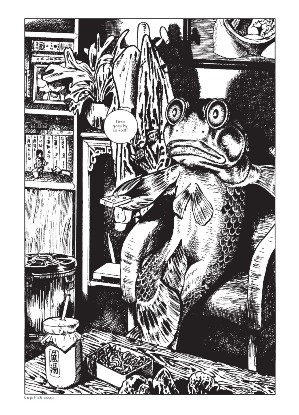

China has a pronounced presence on these pages, its cities and countryside appearing in lush detail, vying for attention with anthropomorphized cats, giant snails, assorted insects, and huge fish that weave in and out of the anecdotes. The overall effect is unsettling, but in the manner of films by Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, a culture admittedly far removed from Ma’s own. There is a point being made here with these elements of magic realism, when lines between the quotidian and grotesque blur. It is an artist’s attempt to address an imbalance; to set right what clearly isn’t.

Travelogues by foreign writers navigating the rise of modern China often speak of how men and women outside large cities simply swarm to urban centres because life as they have always known it is constantly being pushed out to make way for newer, grand ideas. They are often depicted as pawns on a chessboard controlled by shadowy forces they refuse to acknowledge, let alone confront. Placed alongside these missives from foreigners, it is tempting to read Ma’s work as commentary on the emotional toll exacted by his country’s progress on those who call it home.

Night Bus then becomes a book about people who can’t tell real from unreal, fact from fiction. The fine line they walk, taking the reader with them, eventually becomes a powerful comment by an artist who has more questions than answers.

Zuo Ma (W/A), R. Orion Martin (T) • Drawn & Quarterly, $39.95 CAD/$34.95 USD

Review by Lindsay Pereira