There is an early panel in Time Zone J where a version of Roy Lichtenstein’s 1962 pop art painting, Kiss II, appears to show up. One isn’t quite sure about this because the panel in question only hints at that iconic couple, but it feels like it’s present nonetheless, lost among a crowd of other strange and not-so-strange faces. This is a common occurrence when one reads anything by Julie Doucet: the familiar slowly melds with the unexpected to create something new.

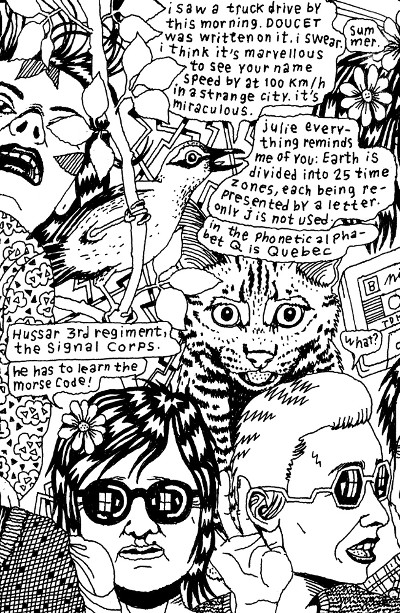

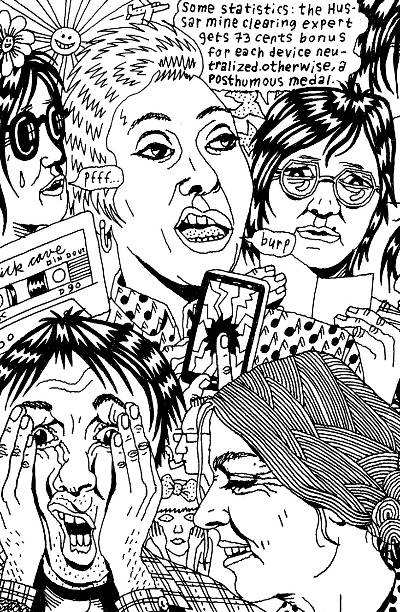

When Doucet puts pen to paper, one suspects she is trying to recreate the stream-of-consciousness that defines how we all engage with our own worlds. Words and visuals collide, almost never in ways that seem conventional. Coherent thoughts jostle for attention alongside images that don’t really fit in. In the process, teasing out a narrative almost becomes like a joint exercise as creator and reader make their way through a page.

What sets Time Zone J apart from Doucet’s oeuvre, stylistically, is the format she chooses to tell this particular story in. Designed to be read from bottom to top, it becomes a continuous scrolling image published in an accordion format. It is an interesting choice for several reasons. On the one hand, we now consume a significant amount of information by scrolling through devices. In 2009, a study by Christopher A. Sanchez and Jennifer Wiley of Oregon State University examined the influence of scrolling on reading time and discovered its negative impact on text recall and/or reading comprehension. On the other hand, a physical scroll changes how we grapple with a story, forcing our attention to some panels and compelling us to gloss over others. It is a surprisingly effective choice for a memoir, more so when the subject is a youthful romance.

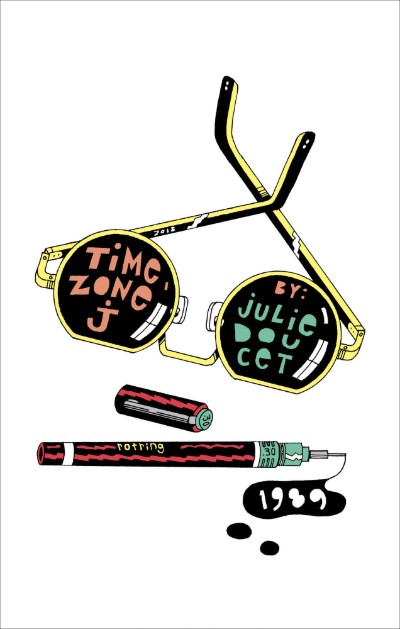

Doucet places herself at the centre, as she usually does, this time portraying herself as the 52-year-old she is today and writing about an affair in 1989 when she was 23. It involves a soldier in France with whom she exchanged letters before agreeing to meet in person. The book opens with her younger selves—aged 12, 16, 19, and so on—and early years as an artist. It harks back to a time of self-published zines (with a sweet shoutout to John Porcellino’s King-Cat) and the relatively open lines of communication between zine creators and their audience. When a young Doucet decides to fly to France to meet with this mysterious reader/pen pal, there is excitement as well as trepidation, not unlike what one feels while travelling to a date with someone discovered on an online dating app. It is that universality across culture and time that gives the book its emotional heft.

At a little over 140 pages, Time Zone J comes across as a deceptively quick read, but its dense collages trigger all kinds of associations that make the experience last a lot longer. It incorporates scraps from journals, with references to a string of artistic and personal influences across three decades, all threaded through with a mix of dialogue, notes, as well as snippets of fevered dreams. In doing so, this becomes more than the sum of its parts, the format becoming an integral part of the story being told.

It all makes for a welcome return to comics. If Doucet intends to spend the next few years experimenting further with the medium, this is a great pointer towards the direction in which she is headed. As for whether Roy Lichtenstein’s Kiss II really appears in that early panel, it doesn’t really matter. Which is probably the point.

Julie Doucet (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $29.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira