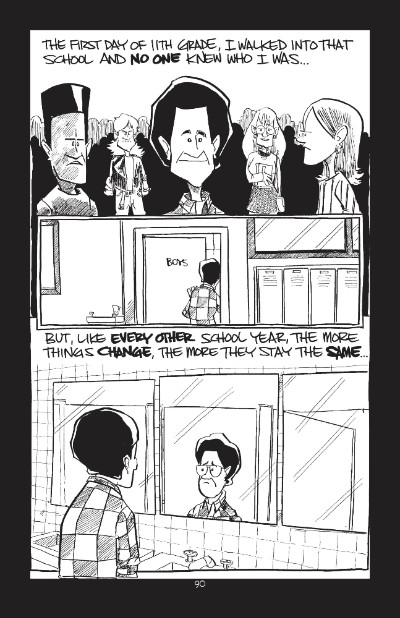

It sometimes feels as if being different in any way often leads to unpleasant experiences of the sort shared by everyone the world over, regardless of nationality, faith, or colour. It marks one in all kinds of ways, especially in school, exposing one to the casual cruelty that comes so easily to the very young.

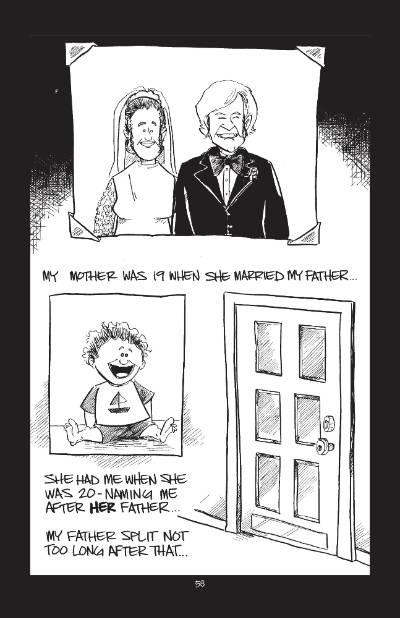

Set in the 1980s, Frank Page’s beautiful self-published memoir, Better Man, begins with what appears to be a story of bullying in New York’s public school system. It evolves rather quickly into something far more powerful though. His eponymous protagonist is a young man abandoned by his father, growing up in a home where his grandfather steps in to play that role. There are other minor characters, but they hover at the periphery of this bond between the young man and the old. It is a memoir of loss, and how we often fail to acknowledge the presence and influence of those who truly matter.

This isn’t to say it is a sad book, because there is also humour in these pages. “Most of the time all you could find on it was static,” says young Frank, referring to an AM-only radio in his grandfather’s car, “but on a new car radio, it was crystal clear static…”

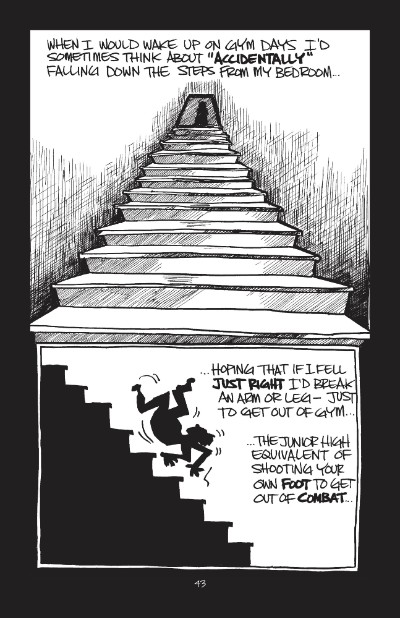

What also gives it poignancy is the kind of art that only a skilled artist can render, where blank spaces say more than crowded panels can. Page uses black and white to powerful effect, his thin lines capturing nuance while larger blocks focus on giving weight to the emotional. Many of these panels are a visual delight, belying the shadow of cartoonists like Peter Kuper, Don Martin, and Dave Berg. One of the pages, for instance, examines how bullies traditionally go about their business in schools, deploying spit bullets, ‘landmines’ that involve feet placed carefully to induce tripping, and variations of hand-to-hand combat ranging from locker slams and forehead slaps to hallway shoves and gut punches. It is to Page’s credit that these drawings use the least amount of ink to carry a lot of information, capturing just how traumatic an experience high school can sometimes be.

The notion of masculinity in literary criticism is always fraught, and Page approaches it with compassion. He isn’t sentimental about his past—his mother’s failed relationships, alcoholism, a father who is a disappointment even on the only occasion he and his son meet—and chooses to highlight moments that redefine what it means to be male.

Better Man sticks to the parameters of a Bildungsroman (the psychological and moral growth of a protagonist from childhood to adulthood) but uses art to introduce nuance and a great deal of tact. It makes for a deeply personal, yet surprisingly universal coming-of-age tale, and answers a question related to its title in the process: who is the better man? Frank Page, or his grandfather?

Page continues to create art in New York City, much of it in the form of a strip about a ‘loud yet subtle’ squirrel named Bob. Better Man is the only longform graphic novel he has created to date, but one hopes it won’t be his last.

Frank Page • Self-published, £10.99

Review by Lindsay Pereira