Room for Love is no conventional, sweet and cheerful, happy-ending love story. It’s a painful, sometimes bitter, account of the unlikely collision of two people’s lives told with sincere authenticity and without any attempt to hold back the blows. This graphic novel really embraces the idea of the three-dimensional, intrinsically flawed character.

Room for Love is no conventional, sweet and cheerful, happy-ending love story. It’s a painful, sometimes bitter, account of the unlikely collision of two people’s lives told with sincere authenticity and without any attempt to hold back the blows. This graphic novel really embraces the idea of the three-dimensional, intrinsically flawed character.

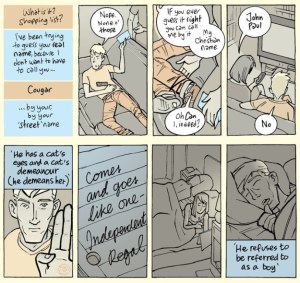

Though there are a smattering of other characters, the only main roles of the text go to its two – very different – protagonists. We’re introduced to them both separately, first the seventeen-year old runaway and male prostitute “Cougar” (a name he gives himself throughout most of the graphic novel), living rough on the streets and getting into trouble, and then there’s the middle-aged middle-class romance writer Pamela, arguing with her publishing agent over her writer’s block and her own adamant insistence that ‘romance is dead’. When their lives intersect on a city bridge Pamela spontaneously invites Cougar into her home and life, and a strange relationship begins to blossom between them, the consequences of which neither of them were anticipating.

Characters are at the core of any decent story, and Room for Love is no exception. Ilya is careful in crafting his characters, neither giving into cliché or over-analysing their decisions. Whether it’s Pamela’s disillusionment with romance or Cougar’s harsh attitude and instinct for lying, the characters’ flaws are what we recognise best about them and what makes the story both believable and compelling. There’s also a sense of enigma to both characters, not just Cougar’s shady runaway past but the hinted at series of events that led Pamela into her own more comfortable but no less lonely life. Reading the graphic novel, you want to know what shaped these characters into the way they are on page, but Ilya leaves many of these questions unanswered – likely a very intentional choice on his part. The narrative is told almost completely through dialogue, which adds another facet of believability but also positions the reader oddly outside of the story’s sphere of action… as an observer looking in.

Characters are at the core of any decent story, and Room for Love is no exception. Ilya is careful in crafting his characters, neither giving into cliché or over-analysing their decisions. Whether it’s Pamela’s disillusionment with romance or Cougar’s harsh attitude and instinct for lying, the characters’ flaws are what we recognise best about them and what makes the story both believable and compelling. There’s also a sense of enigma to both characters, not just Cougar’s shady runaway past but the hinted at series of events that led Pamela into her own more comfortable but no less lonely life. Reading the graphic novel, you want to know what shaped these characters into the way they are on page, but Ilya leaves many of these questions unanswered – likely a very intentional choice on his part. The narrative is told almost completely through dialogue, which adds another facet of believability but also positions the reader oddly outside of the story’s sphere of action… as an observer looking in.

The visual style of the graphic novel itself is pretty straightforward. The artwork comprises of simple but very expressive monochromatically coloured line drawings, mostly laid out across the pages in many small panels. The colouring of the panels deserves a special mention, as there’s a very clever technique to it. In simple terms, the characters are colour-coded – Cougar is a pale orange-y shade where Pamela is a pale blue. Before the two meet their separate storylines and panels are shaded entirely this way, but after their meeting the background fades to a pale white-grey but the characters themselves – their clothes, possessions and speech – retain their original colouring. Really it’s up to the reader how you decide to interpret this. Maybe it’s a simple combining of two storylines, or maybe it rather more disparagingly points out that no matter how close the characters become, their lives are still separate.

There’s a subtlety of storytelling here that isn’t such a common trait in the comic book world. Unlike the manga and comics of Ilya’s career to date, Room for Love is truly a real life story and there’s a powerful, if quieter, drama to that. Certainly the story ends with a glimmer of hope, but don’t expect a fairytale ending. This is a story that leaves loose threads hanging and questions unanswered – a trait that gives it the ability to stick around in your head for days after reading – and that needs more than one reading in order to tease out the details and nuances in the dialogue, art and narrative that you may have missed on a first glance. It’s a story with a raw honesty that demands attention, and one that you won’t regret reading.

There’s a subtlety of storytelling here that isn’t such a common trait in the comic book world. Unlike the manga and comics of Ilya’s career to date, Room for Love is truly a real life story and there’s a powerful, if quieter, drama to that. Certainly the story ends with a glimmer of hope, but don’t expect a fairytale ending. This is a story that leaves loose threads hanging and questions unanswered – a trait that gives it the ability to stick around in your head for days after reading – and that needs more than one reading in order to tease out the details and nuances in the dialogue, art and narrative that you may have missed on a first glance. It’s a story with a raw honesty that demands attention, and one that you won’t regret reading.

Ilya (W/A) • SelfMadeHero, £14.99, 21st November 2013

What an insightful review! I look forward to reading both ‘Room for Love’ and more of your writing!