Like all popular forms, comic books have long been used for propaganda purposes. From Commando War Stories in Pictures to Marvel’s moronic Northrop Grumman collab, they inevitably reflect militaristic orthodoxy. The West prevails over foreign powers, might is proven to be right, and soldiers are unilaterally considered heroes (never villains, and least of all victims).

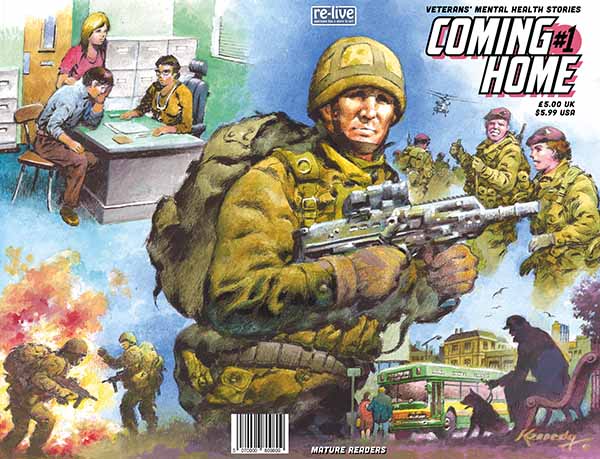

Such stories are as singularly unsatisfying as their big and small screen equivalents, as poppies worn out of social pressure and hypocritically simplistic memory. So it’s properly refreshing to lay eyes on the first issue of Coming Home, a corrective to that unpretty lineage. This anthology series pairs mononymously-credited veterans with a team of artists, who often ape the styles of the form’s more jingoistic forebears, to tell their stories.

That’s perhaps an uncharitable assessment of Commando, and the late, legendary Ian Kennedy — who provided vivid painted artwork for that series as well as Dan Dare and 2000 AD — is on cover duties here, with one of his last published works. It’s a striking image, and a statement of intent, pairing familiar imagery with scenes that are less often seen, yet just as common. Those experiences are expanded on across four stories, taking in conflicts from the first Gulf War to The Troubles to contemporary military life.

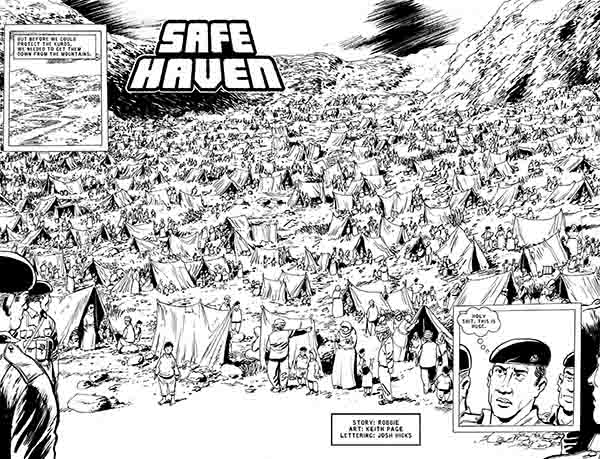

It’s also unfair to single out particular stories as stand-outs, because great care has been taken to pair the veterans with artists whose work complements their recollections. That said, I was particularly struck by the depiction of Robbie’s time in Iraq (above), where he bonded with a Kurdish family over football and shared meals and felt powerless when his unit was unceremoniously returned home. His deployment is rendered in classic 2000 AD-style black-and-white by Keith Page; Robbie’s internal monologue in blunt block capitals courtesy of Josh Hicks. The story is a genuine depiction of fellow feeling between peoples separated by station and state, a crossing of a divide rendered without cliche or sentimentality. Its abrupt ending is a sobering one.

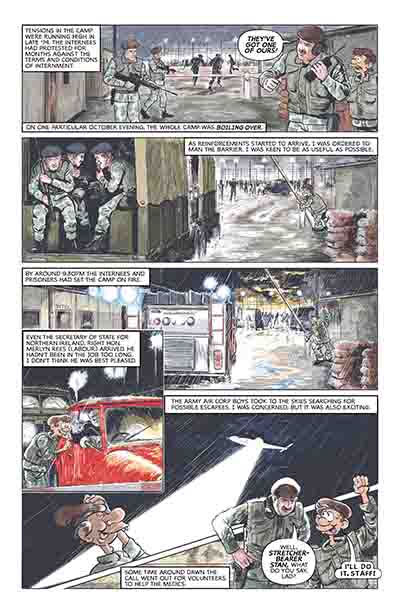

Similarly, ‘Stretcher-Bearer Stan’ (above) uses the tradition of British cartooning to movingly highlight innocence lost amidst the Long Kesh Detention Centre, better known as The Maze. Stan enlisted as a trombone player — a noncombatant. He’s surprised to be posted as a combat medic to Northern Ireland, where he’s soon thrown into the thick of violence. He, too, struggles to reconcile the traumatic intensity of his deployment to the quotidian homelife that awaits him when he leaves, his countrymen ignorant or else uncaring to the conflict across the Irish Sea. Stan is depicted as an exaggerated naif, giraffe-necked and buck-toothed, like Plug of the Bash Street Kids in a flak jacket. Everyone else, and the world around him, are rendered in realistically muddied, bloodied and bruised watercolour. It’s a simple, striking visual conceit.

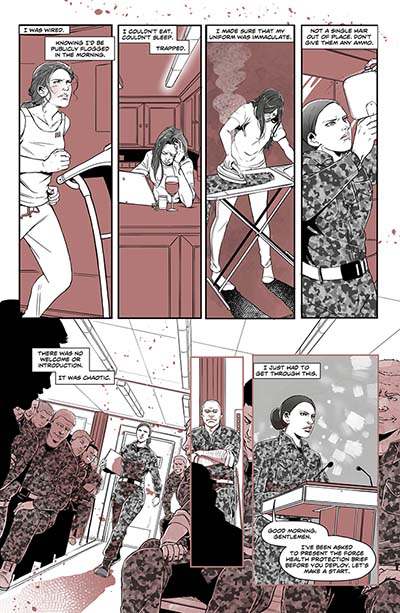

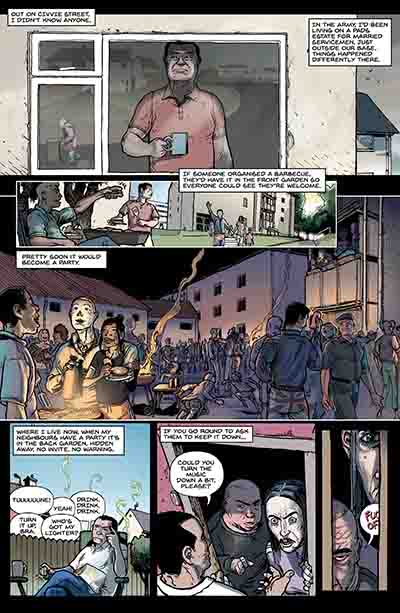

The more modern stories follow the military’s well-documented yet still shocking institutional misogyny, as Claire is heckled through a health seminar without intervention by the sergeant major present (presented in a clean-lined, webtoon style by Emma Vieceli, above); a one-page underground comix paean to the “moral injury” which is carried by all those featured in the anthology; and Clark Bint illustrating Dave’s mental struggle of adapting to civilian life (below), with its lack of structure or easy institutional camaraderie.

I’ve my own mixed feelings about the military. I’m a pacifist, and one who believes the army is more often than not a tool of oppression used by the state to exert its power. My grandad was as an engineer in the Second World War, yet mirrored Harry Patch in his civilian life. A lifelong socialist, he held no truck with the way that conflict in particular is frequently trotted out to bolster nationalistic sentiment and whitewash our colonial history.

Except it’s not as simple as dismissing the institution outright from the comfort of the armchair, is it? Many enlist for what they believe to be legitimate reasons. Many believe it’s their only way to a better life. Regardless of intention or political leanings, a staggering number are left to fend for themselves afterwards, with independent charities taking up the responsibility of those who are left floundering through mental health issues, financial hardship and homelessness after discharge.

Coming Home is admirable as a corrective on two counts: as a break from the history of military comics, effectively using the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house, as well as financially benefiting the Welsh health and arts charity Re-Live. A creatively daring, admirably moral, and consciousness-raising book; here’s hoping the mooted second installment continues the good work.

Robbie, Stan, Claire, Dave (W), Keith Page, Mike Donaldson, Casey Raymond, Clark Bint, Emma Vieceli, Robbie (A), Josh Hicks, Casey Raymond, Emma Vieceli (L) • Re-Live, £5.00

Review by Tom Baker