Maria Medem’s body of work seems to exist as a record of some alternative envisioned landscape. There are certain key formal aspects to her style: a fine, clear-line for example, or a certain approach to colour and texture – but the unity of her style goes further than that: both her comics and commercial illustrations seem to occur in the same geographical place, a very distinct, ethereal location with vast mountainous planes and fluorescent, twilight colours stretching up in gradients in the sky.

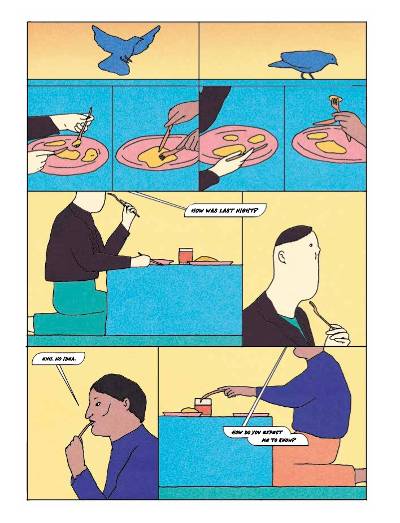

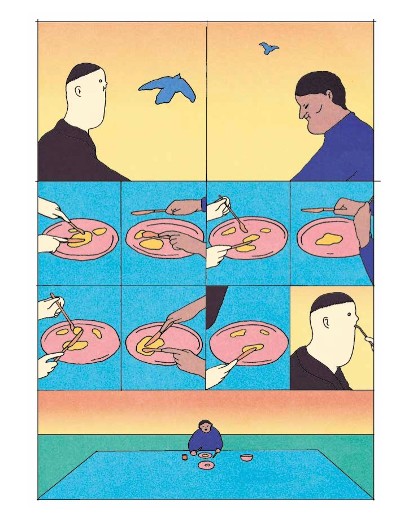

The narrative of Zenith concerns two creatives, one a ceramicist and the other a glass blower, and their meetings within this Medemian landscape. The meetings take place in one of these vast planes, with both men sitting at distant ends of a long, rectangular dining table, to eat and discuss their lives and work. I say ‘men’, but that’s my reading of them: another aspect of Medem’s style is that people can be rendered slightly ambiguously. Each of these characters does have a fairly specific design, but it’s one with a deliberately shifting and amorphous quality, with one sequence even involving one of their faces slowly and seamlessly changing to become the other.

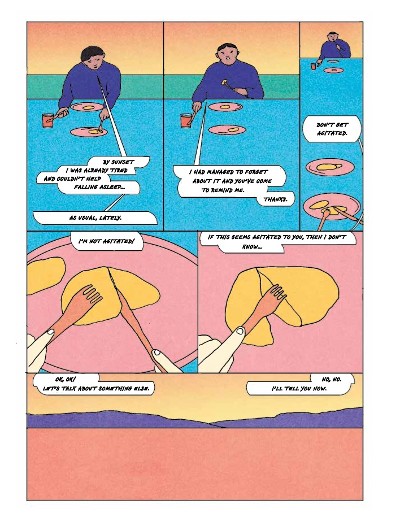

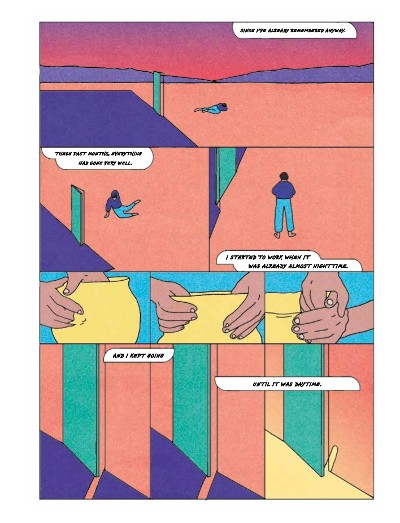

The speech of these meetings is where we understand the drama of the narrative. Both creatives are struggling with their work and with the task of maintaining a productive creative practice in the face of one particular problem: a disorientating and destructive somnambulism. At the book’s beginning, the glass blower has recently experienced the reoccurrence of this mysterious problem. He has woken up somewhere in his home to find all his work has been destroyed. The question hanging in the air is whether he is doing this himself during these sleepwalking sessions, or it is someone else.

The mystery is a fine conceit for exploring Medem’s world and also for her experiments with time and sequencing. Her illustrations have often incorporated narrative and the use of panels, sometimes inserting panels across a wider scene to detail a sequence of action in smaller increments. The effect varies between the soft suspension of time to a testing of its linearity. But the narrative of Zenith also explores themes relating to artistry, the creative life, and how this is impacting on the psychology of the main characters who, despite their occasionally shifting physiology, are fairly distinct as personalities in how they behave and what they say.

The dialogue of their conversations is convincing as speech between two people who know each other well – you could imagine Medem using real life conversations of her own as the basis for these interactions. It feels real in the back and forth patter, the false starts of a sentence and sense of shared understanding that an observer isn’t party to. Taking place in this otherworldly landscape, the mechanics of these interactions seems cast in relief and more noticeable.

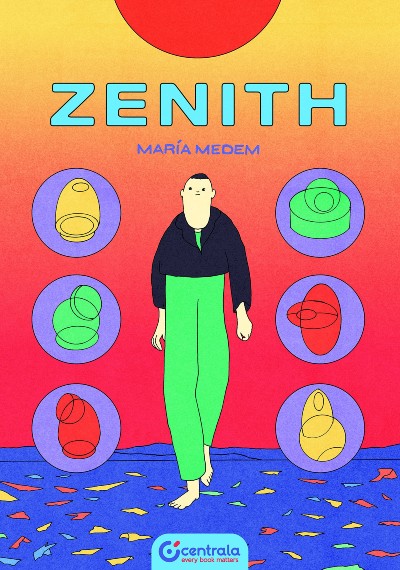

I think it’s possible to define the success of this book in a few different ways. Firstly, it’s a beautiful object, wrapped from cover to cover in Medem’s twilight colour palette and soft grainy texture. Next, Zenith achieves that tricky artistic manoeuvre of balancing the abstract with the specific, with regards to narrative. It’s possible to group this book amongst other contemporary artists whose comics explore the dynamic of text and image and how this interplay produces meaning in the medium. Within this group, the degree to which meaning is left abstract, open-ended and up to the reader can vary.

Despite my enthusiasm for this mode, I admit I can find it testing to stay absorbed over the course of an entire book or even a floppy, if meaning remains abstract and elusive throughout. But that’s not the case here: Zenith shapes itself into a narrative arc largely due to a moment in the latter half of story that is crucial to the former (that’s not a spoiler, it’s in the blurb). In retrospect, this moment is actually quite obvious and the plot is quite simple, but this is what Medem needs to engage in her style of experimentation. She understands that in a comic book, text can anchor the meaning of a story and move it forward, giving the imagery some freedom, and she exploits this facet: the characters say things that clarify context and events while Medem plays with the imagery, drawing things that dance in and out of the field of meaning generated by the words.

Zenith is a beautiful, compelling and mysterious work. Page by page it evokes peace and reverie, at turns inexact or dramatically specific, lingering like a dream that bleeds into waking life.

Maria Medem • Centrala, £24.99

Review by Jon Aye