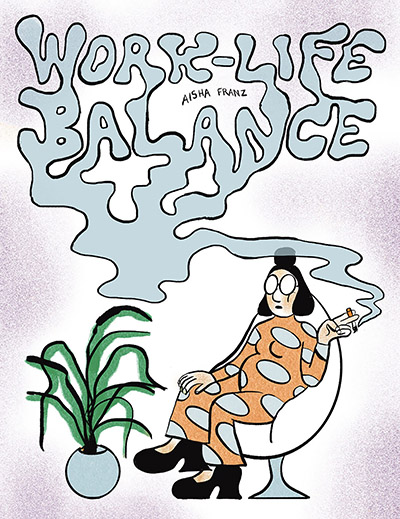

There are moments of recognition on almost every page of German artist Aisha Franz’s latest book; moments that make one nod, then sigh in frustration at the manner in which her characters and their stories resonate. If one assumes Work-Life Balance is meant to be a stinging indictment of capitalism and its dehumanising effects, Franz succeeds magnificently.

The lives of four characters intersect with the indifference of a woman they turn to for therapy. Franz delights in tearing it all down: our influencer culture, the nonchalance with which criticism demarcates good from bad art, and the insidious ways in which corporations extract everything from those responsible for their success. There is a lot of humour in these pages (translated from the German by Nicholas Houde), but Franz also raises difficult questions about consumption and the nature of art.

We asked her about where she draws inspiration from, how she describes her style, and what she would like readers to take away from her work. Here are her responses.

BROKEN FRONTIER: You once described making comics as your way of understanding the world. Was Work-Life Balance triggered by your own questions about our post-pandemic condition?

AISHA FRANZ: The idea for Work-Life Balance started to build way before the pandemic. That’s how it usually goes, I carry characters or specific scenes with me for a while until I end up using them in a story. It was during the two main pandemic years that I actually worked on the book more extensively, but I struggled because the story seemed so mundane and irrelevant during this crazy time of uncertainty. Nobody really knew how or if we would come out of this and it seemed weird to draw a world in which a pandemic and anything related to it didn’t play a role at all.

I also never meant to make a book about “work” in that sense — I wanted to make a book about people whose stories depict a certain time in life, the collective feeling of a specific demographic that I feel adjacent to or part of. Urban millennials from the Global North to be more specific. Then it almost naturally had to be about work and how these people navigate it and struggle with it.

Of course, now, after the fact (and the pandemic) the story might make even more sense. Just as a comic can serve as a magnifying glass on certain issues, so does an event like a pandemic.

BF: Your work always has strong, carefully etched female characters with thoughtfully expressed inner lives. Do you have any literary role models who influence the way you write?

FRANZ: I’m mostly drawn to literature and films that are driven by characters and character development. In film, it would be the ones that show more than tell, for example in a lot of French nouvelle vague and Scandinavian cinema, there is not much dialogue, but a lot is conveyed by mood, camera setting and the framing of each shot. I don’t like it when text explains too much in my work: instead, I try to expose my characters’ inner lives by using similar tools. In literature, I like writing that is light and dark at the same time — I think it’s a duality I am very interested in generally and influenced by. I enjoy the short stories of Raymond Carver, Lucia Berlin and Ottessa Moshfegh, amongst many, many others. Weirdly, mostly North American writers — I’m a kid from the 80s and 90s, generally very influenced by American (pop) culture, haha.

BF: When Earthling was published, you spoke about not wanting to find a recognizable style. Is it safe to assume to have found one by now, given how recognizable your panels are to readers familiar with your earlier work? How would you describe that style today?

FRANZ: I wouldn’t be able to say that my style is recognizable because it changes with every book. I guess that’s probably what I meant by saying that — I don’t want to stick to one look or one topic, I want to be able to change how I do things, even within one book. But I guess others are still able to recognize it as mine and maybe that’s what makes somebody’s work unique generally: it’s nothing anybody could copy because it’s an invisible trait that keeps all the elements in someone’s work cohesive, something not even I could put a finger on.

BF: There is a strong streak of absurdity that runs through your work. Is this an accurate assumption? If so, is it a driving impulse whenever you begin a new project?

FRANZ: Absolutely. Absurdity grounds me. It helps me avoid taking my work and myself too seriously: while working on a book you have to deal with too many frustrations and, sometimes, I feel like I can become too serious. Just like in life. I’m a person who likes to laugh about myself, always have. Adding a layer of “weird” also helps to decipher reality and mostly tragedy. I tend to not reflect on things purposefully, my inner motor just wants to move on from whatever let-down I’ve experienced but tapping into ridiculousness forces me to look at all the facets. Like make it weird, surreal, absurd and you actually get the closest to reality and your true self. It’s the essence of creativity and playfulness.

BF: What would you like readers to take away from Work-Life Balance?

FRANZ: I don’t know, I don’t expect much, I mostly hope it is entertaining to people.

BF: Are there any European artists you draw inspiration from, given that the comics space in English often feels as if it is still heavily skewed towards North American or British creators?

FRANZ: I feel like right now I’m mostly inspired by people more my age and younger working alongside each other — I feel like especially in the German speaking comics world we’re experiencing a moment where lots of amazing books are being made and published, the community is interacting and exchanging a lot and people are drawing inspiration from one another. It’s exciting!

With the riso printer and publisher Colorama I help organize an annual comics residency and publication called “Colorama CLUBHOUSE” each summer in Berlin. I feel like these types of intimate spaces where it’s a lot about sharing ideas, challenges and the love for the art form are the most rewarding in terms of creating and developing new images, stories, etc.

BF: You describe yourself as a ‘creator of content’ on Instagram, where you are popular. What do you think of social media, as an artist who must navigate these platforms?

FRANZ: I would say it’s a love-mostly hate relationship. Instagram used to be a great tool for immediate sharing and discovering new artists and events, but most people will probably agree that it has changed for the worse, since the algorithms are so much more manipulative and sorted to reach specific goals. I feel like I now use it out of habit and a need to “not be forgotten”. Yes, I guess that’s it, “Shit, I need to post something this week or else no one will hire or publish me ever again…” It feels vapid — but also it might be a reason why I think that a lot more is happening in person again: a lot of people seem completely tired of it.

I’m from the Flickr/MySpace generation and I feel nostalgic for these older platforms.

Buy Work-Life Balance online from Drawn & Quarterly here

Interview by Lindsay Pereira