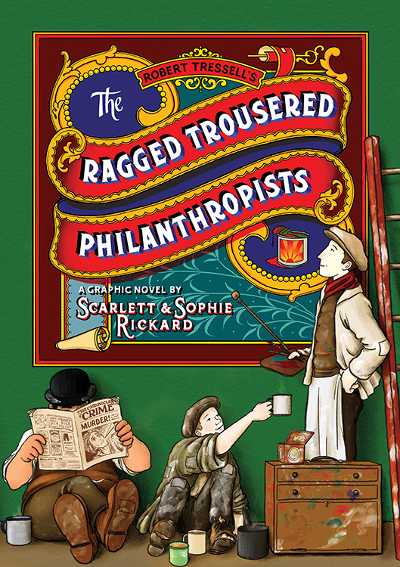

After their acclaimed adaptations of two powerful Edwardian novels (Robert Tressell’s renowned socialist masterpiece The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and Constance Maud’s lesser known but still vitally important contemporary account of the women’s suffrage movement in No Surrender) Scarlett Rickard and Sophie Rickard’s rising profile has seen them nominated for both Eisner and Broken Frontier Awards. Currently working on a third adaptation in their “Edwardian novels trilogy” the sisters continue to remind us that comics as an art form is an incredibly accessible one where social activism is concerned. I caught up with the Rickard sisters to chat about the challenges of adapting prose in to sequential art, the mechanics of their collaboration, and why these novels from over a century ago are still incredibly relevant today…

ANDY OLIVER: You may have had two very well-received literary graphic novels from SelfMadeHero published in the last couple of years but your involvement in the comics world is a relatively newer one. So let’s start by asking you to tell us a little bit about yourselves and your artistic backgrounds, including your first graphic novel Mann’s Best Friend…

RICKARD SISTERS: We really don’t have a comics background! Not commercially, anyway. Scarlett has been a commercial artist and illustrator all her life, and Sophie has done all kinds of jobs from cabin crew to child counsellor. Comics weren’t a big part of our childhood either, although early influences included Posy Simmonds, Raymond Briggs and the work of Janet & Allan Ahlberg.

RICKARD SISTERS: We really don’t have a comics background! Not commercially, anyway. Scarlett has been a commercial artist and illustrator all her life, and Sophie has done all kinds of jobs from cabin crew to child counsellor. Comics weren’t a big part of our childhood either, although early influences included Posy Simmonds, Raymond Briggs and the work of Janet & Allan Ahlberg.

Scarlett has always been a prolific drawer, and Sophie has always loved writing stories, so it felt like a natural development for us to work together, and comics was the perfect medium. We ended up collaborating for the first time on our debut graphic novel Mann’s Best Friend in 2017. It’s the quirky story of a man and his unsuitable dog, with some bank fraud thrown in, set in the Pennine landscape of our childhood. Sophie came up with it because Scarlett wanted a story to draw, and once we’d made one book we got the taste for it.

AO: What are the challenges in adapting books like The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and No Surrender to the comics page? Were there elements you had to abridge or, conversely, expand to make the transition work?

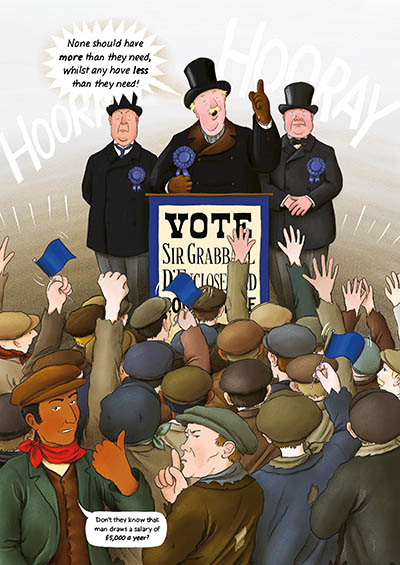

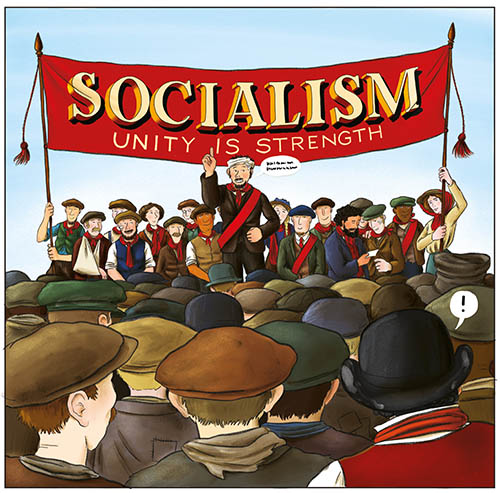

RICKARD SISTERS: The original novel of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists is around 255,000 words long, so it took a great deal of abridging, and some fairly serious restructuring. It’s one of those books which is more often recommended than read, because although it contains impactful and relevant ideas, the Edwardian prose can be dense and hard to get through. It’s not a lighthearted read, and although our adaptation is as faithful as possible to the original in tone, approach and storyline, we hoped to make a more accessible version for a modern audience. Pictures may speak a thousand words, but there was still a lot that got left on the cutting room floor – including an entire chapter of completed artwork!

One of the challenges with The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists is that there’s a large section in the middle of the original book where not much happens. We really wanted our version to have something happening on every page, so Sophie restructured some of it to put things in a slightly different order, which kept the pace going through the story. It has a very large cast too – there were something like 75 characters when we started – so we blended two together into one character here and there to make it easier to follow.

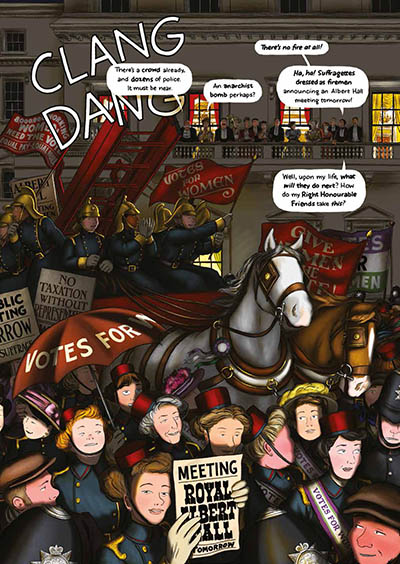

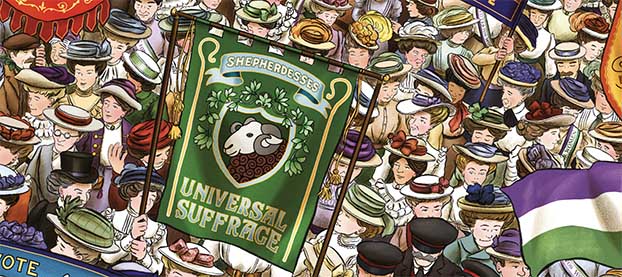

No Surrender was a shorter, more narratively straightforward novel to adapt. The original book is laid out in ‘scenes’ rather than chapters and we barely strayed from the path Constance Maud laid out. It is a book of ‘Deeds not Words’ and we discovered that action takes up a great deal more page-space than speeches. No Surrender is slightly longer, in pages, than The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and the double fold-out demonstration sequence in the final chapter has an additional twelve sides of art.

One of the biggest challenges for Scarlett drawing No Surrender (apart from the huge crowd scenes!) was a whole chapter which follows the courses of an Edwardian dinner party and ends on a dramatic moment as dessert is served. She worked out, using Mrs Beeton’s cookery book, what food they would have for what course, and so the narrative had to move from one course to another while the guests were talking. There was a working-class guest who wasn’t sure of the order of the cutlery, which meant that Scarlett had to learn what he was supposed to do in order for him to do it wrong. If she never has to draw another fork again it’ll be too soon! To quote Our Flag Means Death, they’re such wankers about forks.

A central challenge in translating prose novels to sequential art is how to manage the voice of the narrator and the expression of characters’ internal thoughts. We shy away from exposition or ‘voice over’ text in our books, preferring to stick only to dialogue where we can. This means that the art has to do more of the work, and it also means that sometimes we need to manipulate our characters into situations that allow them to voice their feelings aloud. Sometimes they might be talking to an animal, and sometimes they might be breaking the fourth wall to talk to the reader.

AO: How much research goes into adapting books like these? How do you approach that aspect?

RICKARD SISTERS: Both The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and No Surrender were written and set in pre-WWI Britain and in a very particular political climate. In order to do the stories and themes justice we have to understand something about that world and what it was like to live and work there. Scarlett draws a lot of detail on every page, and it’s important for realist world-building to make sure that the domestic details of the characters’ lives are accurately portrayed. People’s clothing, food, transport and homes all say something about their economic circumstances too, so there are lots of micro-decisions to be made. As well as being historically accurate, the details need to be right for the story and the character. Scarlett thrives on that kind of detail (as does our editor David Hine), and she loves researching elements for the books.

Practically-speaking, she has developed systems which make it easier to keep tabs on research materials. She uses Pinterest boards to assemble furniture for a room, for example, or for upper-class fashion, or for suffragette banners, so she can easily look in one place to find reference material. We were lucky that we grew up in a family which was very interested in period architecture, domestic history and politics, and were immersed in these themes from an early age. Our grandparents particularly had lots of weird Victorian kitchen implements and they’d show us how to use them, so a lot of that stuff is still in there somewhere!

We have had some funny situations when researching. In No Surrender there’s a chapter in a church, and we spent ages picking which hymn numbers should go on the hymn board because we knew David Hine wouldn’t be able to resist looking them up. The chapter opens with the congregation singing Onward, Christian Soldiers, so we smugly included that number on the board. But when we sent it to David he said, “I see you have Onward, Christian Soldiers as the second number on the board, but they’re singing it as the congregation’s coming in so it should be the first one.” So we had to go back and re-do them all! That’ll teach us for trying to be clever!

AO: How do you collaborate as a creative team? How does that process work? And what did David Hine’s editorial input bring to the table?

RICKARD SISTERS: We have a very clear and straightforward division of responsibilities between words and pictures, but we work together very collaboratively throughout. Sophie starts by producing a kind of screenplay script of the novel, and separate notes on locations and characters. We then work together to rough out a storyboard, translating the script to the page. From what we understand of how most other writer/artist collaborations work, Scarlett has much more artistic direction of what goes where on the page, and in each panel. Then Scarlett uses the storyboard to lay the book out, and then draws and colours each page one by one, sharing the artwork as she goes along. That way, Sophie gets a nice surprise in the evening and we discuss any changes together.

David Hine has taught us so much about the art and craft of comics, and we really rely on his feedback. He was brought to The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists project by SelfMadeHero because of his familiarity and connection with he original work, and he helped us through some really difficult challenges with the adaptation. That book really was our Beatles in Hamburg moment, it was a baptism of fire into the worlds of adaptation and comics, and he was great at gently pointing out ways we could improve our craft. We asked for him again for No Surrender, and for the book we’re working on now. We have developed a pattern of one set of revisions at the script stage, then getting in-progress feedback chapter by chapter, which is invaluable. Having an extra pair of eyes outside of our direct collaboration is really helpful too in case we accidentally miss something because we’re so close to the material. SelfMadeHero have also put us together with a great proof reader in Nick de Somogyi, who is a stickler for punctuation and accuracy, so by the time the book is ready to go to print we have about as much confidence as we can have that it’s all okay!

AO: Speaking of process, Scarlett, what mediums do you work in? And can you give us background on some of the design decisions on the books like the evocative use of chapter breaks?

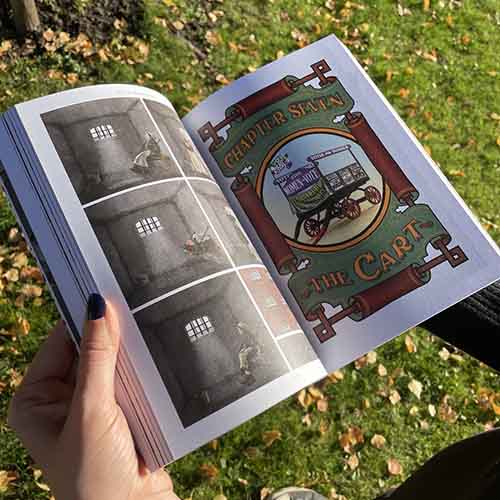

RICKARD SISTERS: Our first book, Mann’s Best Friend, was drawn on paper and coloured on an iPad in the early days of Adobe Sketch. Scarlett had just been paid for a large job for a client so she bought herself an iPadPro in a rare moment of frivolity! Little did she know that that would change her life completely. All the artwork for The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and No Surrender has been done digitally on the iPad in Adobe Fresco, which is the new version of the Sketch programme. She used that program because she already had the Adobe Creative Suite for her other work, and it syncs with Photoshop and InDesign in a fluid way. She lays the book out with the panels in InDesign, and then everything else is drawn on the iPad. At first she felt a bit ‘dirty’ about doing everything digitally – there’s something uncomfortable about not having originals. But it’s so much easier on the hands (we both have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, which is a connective tissue disorder), and it means she can draw lying down without her pen running out!

We decided on the chapter headers because The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists is such a long book, we felt that we should make natural breaks for the reader to stop and rest. The chapter headers work like a sort of Edwardian sorbet! A palate cleanser before you get into the next bit. Scarlett based them on graphic art of the era – around 1910 – a lot of the inspiration came from packaging, adverts, cigarette cards and printers’ sample books.

AO: Why do you think books like The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and No Surrender are still so resonant and relevant in 2023?

RICKARD SISTERS: We chose to adapt these stories because of their enduring relevance and the poignant messages they hold for modern readers. The stories were written more than a century ago, yet the underlying themes are just as applicable to our modern lives. The structural economics depicted in Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists describe the current so-called ‘cost of living crisis’ so well. And although ‘Votes for Women’ seems like an outdated argument, the ethics of civil disobedience to change laws are as urgent as ever. The arguments in No Surrender are constantly rehearsed across the UK and North America in the ‘culture wars’ and disputes over reproductive healthcare. The day these books become irrelevant to our lives will be a good one, but we’re not there yet.

AO: And, finally, what are you both working on next, either in comics or in other areas of the arts?

RICKARD SISTERS: We’re working on a third adaptation for SelfMadeHero, to make a kind of trilogy of political novels from 1910s Britain. This time it’s This Slavery by Ethel Carnie Holdsworth, who worked in Lancashire cotton mills from the age of 11. It’s an angry, hot-blooded story of two sisters who take different approaches to managing adversity, with themes of industrial dispute and the intersection between capitalism and the patriarchy. What is the difference, the book demands, between being ‘owned’ by your employer by the hour and being ‘owned’ by your husband by the night? The book will be similar in length and style to the previous two, and appeal to a similar readership. We’re well on the way with the adaptation process, and planning for publication in 2025.

For more on the Rickard Sisters visit their website here.

Buy the Rickard Sisters’ work online here.

Interview by Andy Oliver