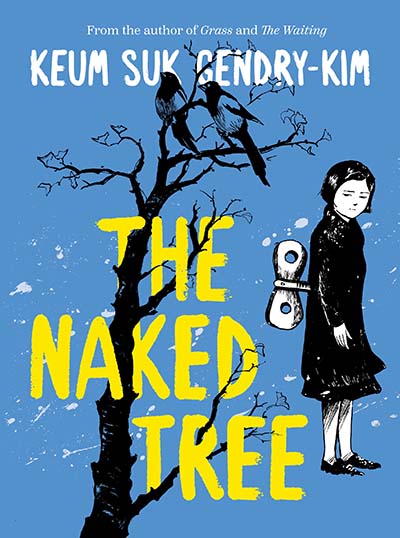

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s third novel, translated by Janet Hong, is her first adaptation, but does not seem particularly out of step with her oeuvre. The Naked Tree was writer Park Wan-suh’s first work, published in 1970 when she was 40. By the time she passed away at 79 in 2011, her novels and short stories had turned her into a revered figure in South Korea. Why Gendry-Kim chose to adapt this and not one of Park’s later books has everything to do with the war fought between North Korea and South Korea from 1950 to 1953, and its impact on the collective psyche of both nations.

It was a conflict that separated Gendry-Kim’s mother from her sister (beautifully depicted in her second book, The Waiting), and Park from her own family. With three million fatalities and more civilian deaths than World War II, the Korean War is now considered among the most destructive of the modern era.

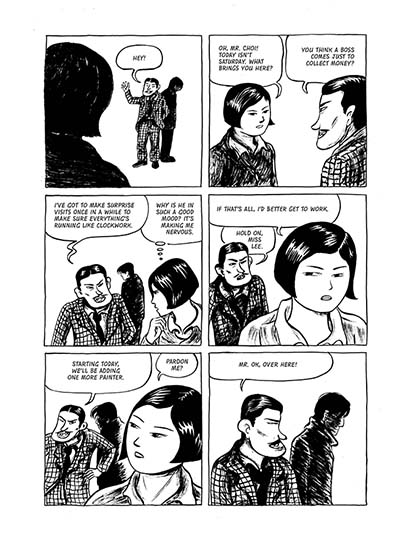

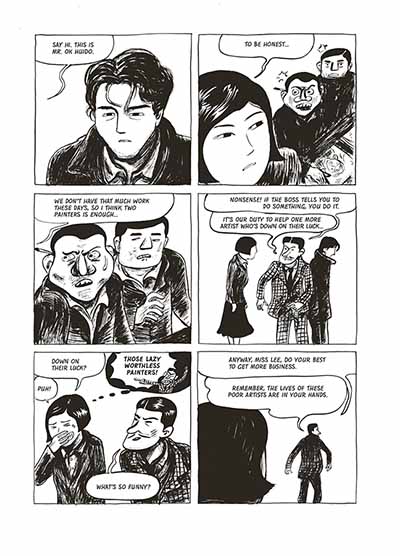

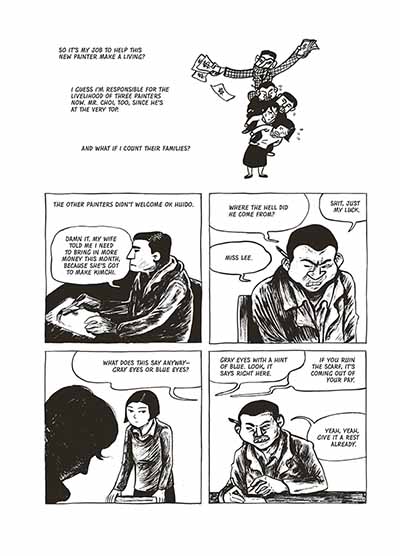

As a genre, what defines war literature across the globe is its emphasis on horror and atrocity, coupled with insights into human nature, heroism or cowardice, and the often overwhelming question of morality. Gendry-Kim breathes new life into Park’s much lauded and nuanced study of families struggling with loss, poverty, and the erasure of social bonds. The Naked Tree is about 20-year-old artist Lee Kyeonga who is trying, with her mother, to make a living. They dwell in the shadow of trauma, coming to terms with the deaths of two family members, and the ordinariness of their situation is a powerful comment on how millions were compelled to simply pick up the pieces and try to carry on.

Kyeonga is infatuated with a painter who happens to be married. There is also an underlying thread about racism playing out in the background, given that she works at the US Post. This makes sense given that the novel was set in the 1950s, when South Korean anti-Americanism was at its peak, thanks in no small part to the behaviour of American military personnel. Kyeonga must navigate not just the complexities of being a female survivor in a patriarchal country, but also accept the gradual erasure of her identity and sense of self. It is a coming-of-age story, but one that bucks the trend of how these tales usually evolve because the war turns Kyeonga into someone she was never meant to be. Her tragedy becomes a microcosm of what South Korea had to contend with for decades after the war.

Gendry-Kim’s approach to art continues to be fluid and, although her style is now recognisable, it is interesting to consider her response to a question once posed about her influences. She rejected the idea of a set of rules for making a graphic novel, and her panels reflect that. For instance, she often breaks away from a straightforward narrative to introduce full-page illustrations such as one where Kyeonga’s mother’s “superhuman strength” is depicted by merging her body with the trunk of a tree.

The book ends with a revelatory essay by Gendry-Kim on artists she has loved, explaining why she chose Park Wan-suh. One realizes that while it is easy to categorise The Naked Tree as war literature, it is also important to acknowledge Gendry-Kim’s clear-eyed understanding of an artist’s role while documenting history. She once spoke of wanting to show not just the violence of war, but the resilience of people who lived through it. She also added that the themes of all her books were connected and, even though this story comes from Park Wan-suh, one can’t help but sense the ghosts of Gendry-Kim’s own past hovering in the margins.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim, Park Wan-suh (W) Keum Suk Gendry-Kim (A), Janet Hong (T) • Drawn & Quarterly, $29.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira