It’s always interesting to look at recurring tropes in literature, and this is particularly enjoyable when it comes to fairy tales because of how they reflect the commonality of our experience. Fairy tales come into being for multiple reasons, and one of their most important roles is how they generate models of behaviour for the young. However, when written for an older audience and in the hands of a powerful storyteller, they turn into complex morality tales that surprise and delight. Egyptian artist Deena Mohamed is that kind of storyteller.

When she was 22, Mohamed decided to create her own version of a fairy tale using an intriguing protagonist. Her heroine was a hijab-clad superhero named Qahera who took on everything from misogyny and Islamophobia to the repressive state under which her country’s young people struggled to find freedom. Qahera appeared as a webcomic in 2013, at a time of protests in Egypt that soon engulfed other parts of the Middle East. She tapped into the zeitgeist in ways that encouraged Deena to expand her canvas and Shubeik Lubeik arrived two years later, in Arabic, until a slew of translations followed.

Egypt has always had a rich tradition of written and oral tales passed down through generations, and many of them—The Doomed Prince, The Princess in the Suit of Leather, The Woodcutter and his Daughters—grapple with universal ideas that involve fate, destiny, and virtues such as bravery that separate heroes from commoners. What Mohamed does, at least on the surface, is tap into something as universal: in this instance, the possession of wishes and the possibility that they might come true.

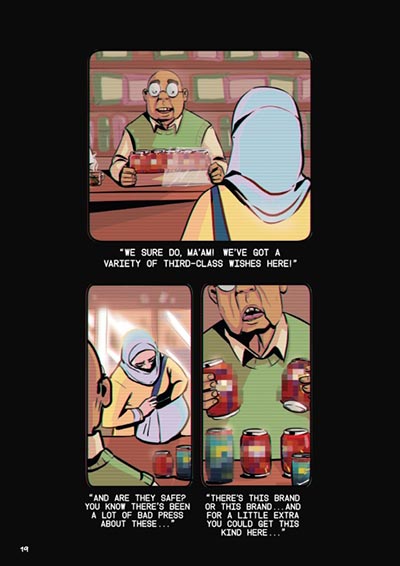

Set in a Cairo where wishes are real and available for sale at neighbourhood kiosks, her world makes the magical mundane, but does this by subjecting it to the vicious, restrictive forces of capitalism. It is a society with access to life-changing power, but also one still held back by corruption, bureaucracy, and vices we have been condemned to grapple with since the dawn of civilisation. She exposes these harsh truths with the lightest of touches.

Split into three parts (originally published as three separate novels), Shubeik Lubeik has three protagonists and their stories involving ‘First Class’ wishes — the highest, most powerful kinds for sale. There’s heartbroken widow Aziza; rich and depressed college student Nour; and Shokry, who is struggling with a crisis of faith. Each wants a First Class wish to change something about their lives, but their choices eventually reveal not just their deepest desires but make the rest of us question our own priorities. A fun story slowly turns into an eye-opening moral lesson about humanity’s capacity for good, as well as our proclivity for evil.

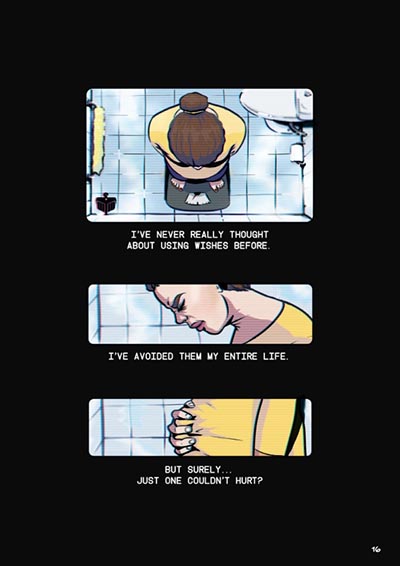

Mohamed makes pertinent comments along the way, about colonialism, religion, exploitation, and even how society looks at mental health. She does this with effortless humour and the kind of emotional intelligence that comes only to writers who genuinely empathise with their characters. She also displays a keen sense of economy, sometimes using a single panel to give us insights into what a character’s life has been like until that point. It’s easy to see, in some instances, how her experience with creating art online has influenced how she can fit a lot of information into bite-sized boxes.

The wishes in Shubeik Lubeik become metaphors for what we all desire, as well as how we are never in control despite how much we want to believe that we are. It is deserving of the praise it has already garnered and I can’t wait to see what kind of story Deena Mohamed decides to tell us next.

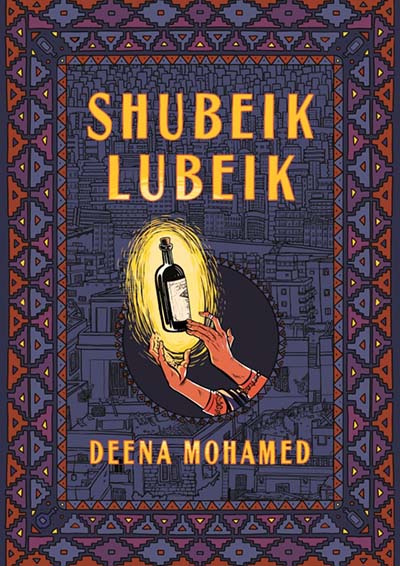

Deena Mohamed (W/A) • Pantheon/Granta, £19.99

(Published in the UK under the title Your Wish is My Command)

Review by Lindsay Pereira