In 2021, the English translation of French illustrator Mirion Malle’s This is How I Disappear taught us to question how we look at sexual assault and its devastating impact. It was a weighty topic, but treated with sensitivity and the kind of empathy that few artists manage. Malle has never shied away from difficult topics, and her latest work—translated again by Aleshia Jensen—tries to answer questions she has always grappled with. Even her first book, The League of Super Feminists, took a close look at consent, gender, body image, and other subjects that occupy young readers, with a lightness of touch.

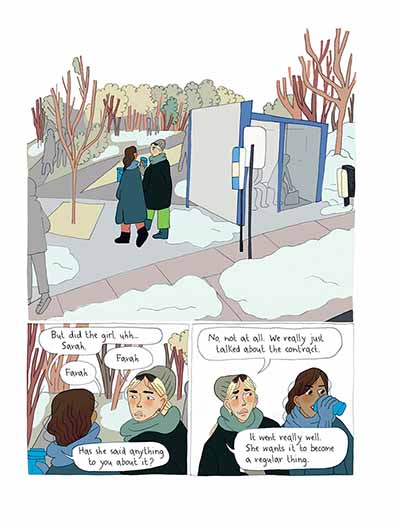

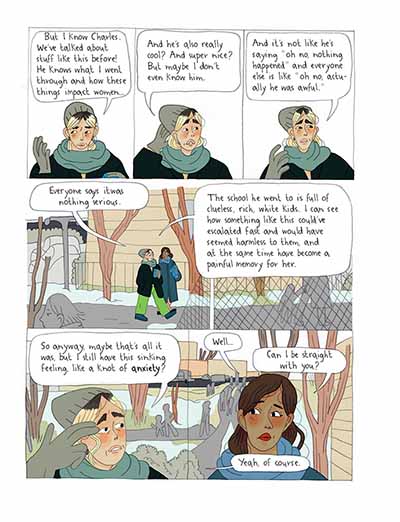

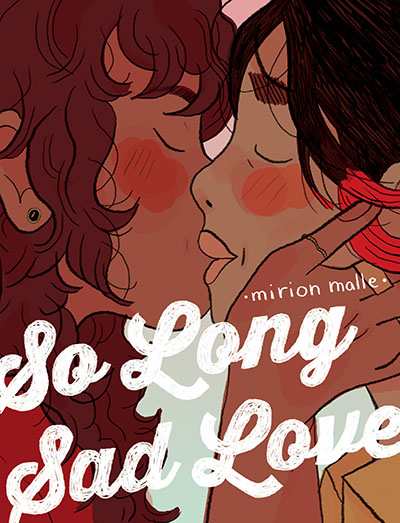

There are echoes of similar questions, about gender identity and what it means to conform, in So Long Sad Love, translated again by Jensen. Malle’s protagonist this time is Cléo, a woman coming to terms with the realization that her partner Charles hasn’t been honest with her about his past. An eventual erosion of trust prompts her to look not just at her relationship from a new perspective, but also her life choices shaped by forces that erase her own needs and expectations from the equation. There is something reassuring about how she rebuilds herself— like the journeys that filmmakers like Nora Ephron took us through time and again—but that familiarity is also what makes it so moving.

Malle sets the tone for Cléo’s path to redemption through her choice of epigraph, a quote from the film Cléo from 5 to 7, written and directed by legendary filmmaker Agnès Varda in 1962. “I don’t think I’m afraid anymore,” says the character Cléo from the film, “I think I’m happy.” Like the film, Malle too uses her protagonist and the people she interacts with to create a sense of solidarity that is often missing when artists write about women. The solidarity is almost always male, expressed in this instance by how Charles’ friends support him despite his questionable behaviour. What Malle does is show that women can lean on each other, flipping stereotypical depictions that often portray them as rivals. This solidarity eventually allows Cléo to arrive at a place of clarity.

So Long Sad Love also shows how Malle has evolved as an artist, her full-colour panels revealing a subtle but undeniable use of colour to evoke mood and emotion. Her choices for panels involving Charles are at odds with tones used to depict Cléo when she interacts with female friends.

Interestingly, in 2021, Malle was asked by American artist Sophie Yanow about the Bechdel test, used to measure the representation of women in film and other fiction. Yanow wanted to know if she subscribed to the concept intentionally, or if it felt like a natural reflection of life. Malle responded by saying it was a bit of both, adding that there was a political aspect to representation. “I write about stuff that I know and observe,” she added, “I don’t want to create work that copies reality precisely but rather something that brings out the feeling of real life, of lived experience.”

That response goes a long way towards understanding what compels Malle to create the stories she does. One can sense that she thinks deeply about situations she places her protagonists in, as well as the forces that shape them and their decisions. It makes for books that are short but satisfying. So Long Sad Love can be read in a single sitting, but the ideas it explores tend to linger for days. One assumes Malle wouldn’t want it any other way.

Mirion Malle (W/A), Aleshia Jensen (T) • Drawn & Quarterly, $24.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira