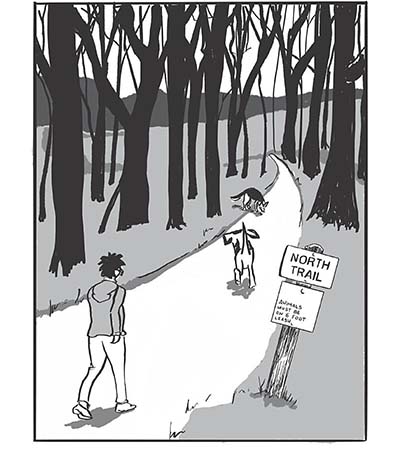

“To everyone who wonders if you have a story worth sharing… you do.” These profound lines open Elizabeth A. Trembley’s eye-opening graphic memoir Look Again, a refreshingly truthful and personal look at how trauma can affect your life. Simply titling the first chapter of the story ‘Trauma’, Trembley doesn’t beat around the bush when explaining what happened to her in 1996. Another ordinary day, Trembley is walking her two dogs in the woods. Following the North Trail, she sees a scene that will haunt her for the rest of her life: a dead body, hanging from a tree.

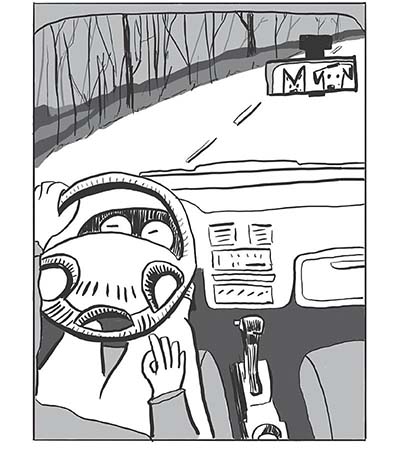

How this is depicted really makes the reader feel Elizabeth’s terror – the initial wordless, picture-perfect pages are torn up into little pieces, until there is nothing left – a heartbreaking visual representation of Elizabeth’s mind fracturing at the sight. In amongst fragmented snapshots of the body, Elizabeth’s panic is apparent through her language – mostly repeating ‘no’ and ‘dead’ in an erratic scribble, imagining scenarios of how the man may have been killed, and worrying that her discovery of the body means she will be next: “Do not look again. Get out of here.” The following sketches are much more childlike and less defined and show that Elizabeth is returning to the primal human instinct we all have from birth to flee from danger. Shaded in chalky blacks and greys, Elizabeth’s state of mind becomes increasingly childish in her panic, imagining herself as a tortoise “slow and steady wins the race” and going at “warp speed” out of the car lot. Later, her legs spiral at an abnormal speed, like Woody Woodpecker, and her lungs “snap, crackle and pop” as she runs away.

From here, we move on to how Elizabeth has dealt with her trauma in the years that follow, and through her, we live through six variations of this same event. Starting with variation one, Elizabeth chooses this version of the event to be told mainly through her art. This picks up right where we left off last time and lets us know that Elizabeth did indeed call the police at some point after her discovery. The reader can feel her inherent anxiety through the depiction of her inner voices: Dragon, Hawk and Danger Pickle. Dragon represents stoicism and critiques Elizabeth for being too emotional and overreacting, Pickle sees danger at every turn, and Hawk hones in on control and focus. The clashing voices in her head make the situation even more heightened, as she draws a map to the dead body for the policeman, all the time worried about being arrested, appearing too emotional or even too detached. Through a visual depiction of her stomach as a maze, all tangled up and confused, we begin to understand just how much this has affected Elizabeth – the woods used to be her safe place, somewhere she felt a sense of peace: “Things make sense, I can feel safe.” This haven has now been completely ripped away, leaving behind a feeling of loss and dread.

Each variation pushes the narrative forward, by revealing more details about that day through a different retelling; Elizabeth informing family members and her work what has happened, in which she is more factual and detached; giving a lecture about the event to budding writers, in which we find out more about Elizabeth’s thoughts as she ran from the body to the car; a written account focused on the dead man’s perspective, how helpless he must have been feeling to take his own life, and how Elizabeth can now identify with that hopelessness. I won’t go into too much detail on the other variations but suffice to say, the memory of this day becomes more vivid and detailed with each addition, ending in a beautiful full circle moment, in which Elizabeth decides to tell her story through the medium of comics, and Look Again comes into fruition.

For Elizabeth, it is the realisation that her world view was shattered that day, that helps her to rebuild and feel at peace once more: “The worst injury from a traumatic event is not a specific physical or psychological impact. It is the shattering of the fundamental beliefs that structure that person’s worldview.” Through therapy, and various outlets like writing, drawing and speaking with family and friends, Elizabeth reclaims that part of herself she lost in the woods that day and ultimately is stronger for it, even discovering past trauma and being able to work through it. With a thought-provoking note from the author towards the end of the book, Trembley reinforces the quote from Hildegard of Bingen that she aptly chose for the very first page: “Part of the terror is to take back our own listening, to use our own voice, to see our own light.”

Elizabeth A. Trembley (W/A) • Street Noise Books, $20.99

Review by Lydia Turner