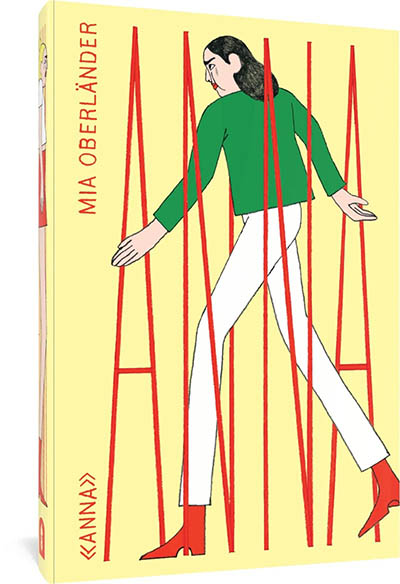

Mia Oberländer’s debut graphic novel Anna has already made its mark despite only being published this year: Awarded the Berthold Leibinger Foundation’s Comic Book Award, the German Youth Literature Award and being published in six different languages. Translated from its original German by Nika Knight, and published by Fantagraphics, this modern-day folktale is a tour de force, a Germanic fable of generational trauma and radical female acceptance.

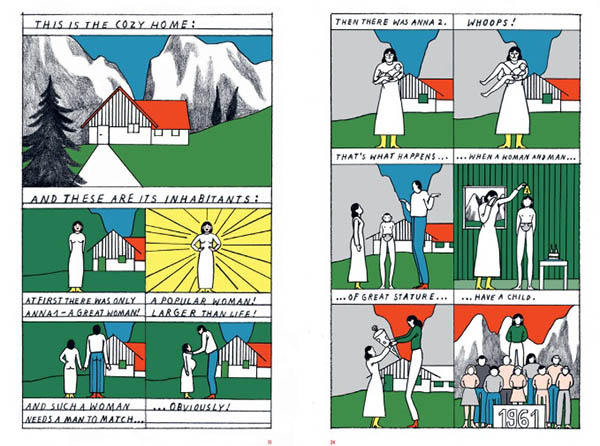

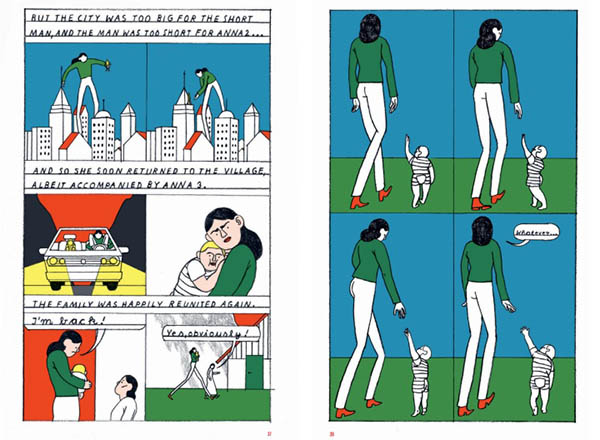

Anna is written in diary format, with calligraphic, scribbled handwriting on lined paper, followed by an illustration. Our story begins with a third iteration of the ‘Annas’ – a family of disproportionally tall women, who are shunned by their town, Bad Hohenheim. The third-generation Anna retrospectively tells the tale of her mother’s birth as an abnormally large baby through a framing device narrative. Due to her grandmother’s ‘normal’ stature, good looks and status as a third-year running Christmas Tree Queen, the town begrudgingly accepts the startling large child. Yet, this second-generation Anna is taught to behave differently from the very beginning, even by her mother: “We can’t do anything about [your height] … but we can behave appropriately”. Anna is cruelly told that only repressed gay men, the masochistically inclined or those wishing to be dominated could be attracted to such a tall woman. With exaggerated, gangly legs, Anna often tries to fold into herself, knees up to her chin, trying to take up as little space as she can, so as not to disrupt the ‘norm’. But when her own daughter is born and is equally as tall, this Anna is determined not to let the generational trauma carry on.

It seems that in this Germanic town, that looks so ideal, lush and green, anyone remotely outside the norm is shunned – first-generation Anna is even temporarily loathed as a child because of her sweet, lanky dog (who doesn’t look like a dachshund is supposed to). Ironically enough, none of the villagers look what would be considered ‘normal’. They’re all drawn slightly grotesquely and exaggerated, with close-ups revealing their oddly framed faces, which are almost Picasso-like. There’s something very sinister about the way Oberländer illustrates the townsfolk – girth aside, ironically, the Annas are some of the most ‘normal’ looking people in the town, with softer proportions. In a story within a story, fables of giant women who could ring church bells and reach mountains are told – but these Annas? They’re not as startlingly tall as I expected from the cover of a giantess weaving between letters. Featured also are men who are just as tall, if not more so – yet they seem to have no struggle being accepted by their peers, a point about sexism the author clearly wants to drive home by featuring these types of characters without comment.

The illustrations of people are incongruous compared with the idealistic, mountainous landscape, but are often humorously exaggerated– the first-generation Anna’s legs gesticulate wildly out of her pram in a flashback and gangly limbs hover over skyscrapers a la Godzilla in another panel. Oberländer shows her versatility as an artist when her style changes for a chapter around midway through, depicting second-generation Anna’s frustration over her unfair treatment. Traversing from wooden-toy like town scenes (Erzgebirge in Germany is famous for its wooden toys) to rough, bolder plains of colour, the entirety of this chapter consists of Anna screaming, as the lush landscape around her becomes hellish, engorged and enflamed – almost apocalyptic.

The lettering is fantastic, adding a real personal touch to every page as we see Anna’s frustration through her shaky handwriting. As Germany is a country rich in its folklore and fairytales, I enjoyed seeing how Oberländer incorporated classic aspects of this tradition into Anna, like featuring a romanticism of natural spaces and a wandering protagonist ousted by society.

The real driving force of this narrative is its feminist allegory; the Annas are, quite literally, too big for their narrow-minded town. Oberländer’s point here about female autonomy could not be clearer: women should not have to fear taking up space or make themselves small to fit into the box of traditional femininity. Long may the era of graphic novels that promote this radical message last.

Mia Oberländer (W/A) Nika Knight (T) • Fantagraphics Books, $24.99

Review by Lydia Turner