Marketed as a provocative re-imagining of the infamous Greek figure, Medea from Dark Horse Comics seeks to change the lasting impression of the sorceress that has remained notorious through the ages. With some subtleties between retellings, the epithets of villain, barbarian, witch and occultist continue to be associated with Medea as her story has been passed down through history. This is something that writer Blandine Le Callet and artist Nancy Peña seek to remedy in their modern-day take on Medea’s story, told in her own voice, translated into English for the first time by Montana Kane.

A little context on Medea is useful before diving in. Medea is a figure in Greek mythology, featured heavily in the works of Ovid, Euripides, Seneca and other ancient Greek writers. The etymology of her name can be traced back to the word ‘schemer’, and though there are many variations of her story, they all end in bloodshed and tragedy for the enchantress. Despite being vilified throughout history through the writing of male scholars (are we surprised that sexism was alive and rife in ancient Greece?), modern schools of thought seem to view Medea with a more sympathetic gaze, as a woman who was simultaneously a victim and villain. So… who is Medea?

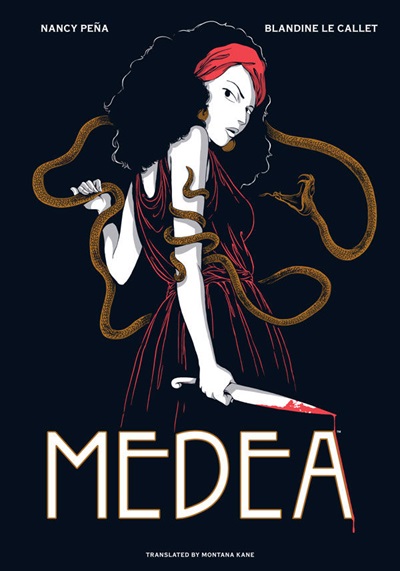

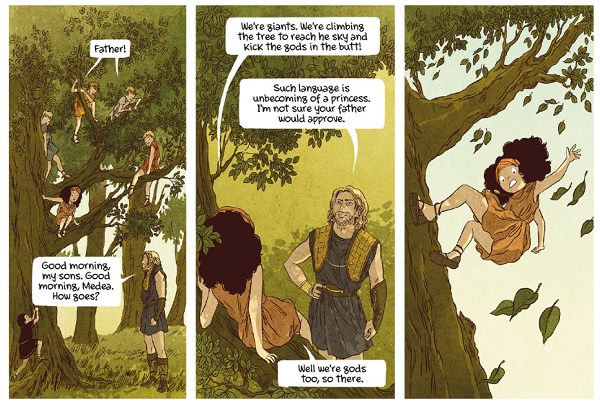

According to Peña’s cover art, a dangerous figure to become entangled with. Dressed in crimson, with a poisonous viper circling her neck and a bloody knife dripping onto the title lettering, Medea already seems every bit a villain in her first impression. Yet, the narrative begins during her childhood in Colchis, as a sweet, carefree girl who wants to play with her friends. Medea is the king’s daughter, beloved by her family and well-protected, being descended from Greek gods. Her father Aeëtes is a powerful and violent man, with a hatred of his eldest daughter, though he dotes on the younger Medea. But there’s a problem: because of the constraints of the period, the only legitimate heir to the throne is Medea’s sickly younger brother Absyrtus – a fact that causes much chagrin and bouts of anger from the king. Obsessed with gaining knowledge from ancient Egyptian scrolls and priestesses of the goddess Hecate, King Aeëtes is determined to ‘cure’ his son, no matter what the cost. It is this fixation which fuels his paranoia, leading to the catalyst for the tragedy to follow.

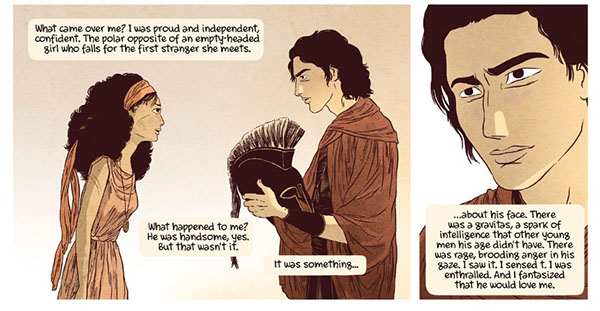

Medea begins to study under the tuition of the temple of Hecate, feeling freed by the balms, cures and elixirs she can conjure. But her father’s ulterior motive for this education is clear; he hopes that Medea will become learned enough to cure Absyrtus. When this aim doesn’t grow to fruition, the king grows crueller, targeting members of his family. This eventually leads to the introduction of Jason, famed for the myth of Jason and the Golden Fleece, Medea’s subsequent marriage, and introduction to a world outside of her father’s cruel reign. Sadly, for those who know the myth well, Medea’s tragedies have barely begun.

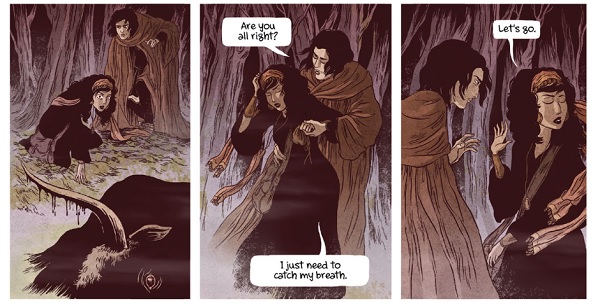

It was so interesting to experience Medea in a completely new light – in the original Greek myths, she’s depicted as barbarous, calculated and cold, but in Medea, horrific events happen around her, are out of her control, or have some kind of logic behind them. Medea is also likeable, despite her morally ambiguous actions; she’s learned, powerful, liberating, and refuses to be confined to the role of mother and wife. Given this, it’s easy to see how the men around her managed to twist her narrative, making her actions much more sinister, and turning her into a monster. As Medea herself says, ‘why have I been depicted as the worst monster of all?’. Why is Medea remembered for her actions, when men, who have done much worse, are allowed to slip through the cracks?

The amount of copious detail from writer Le Callet is admirable; the thorough appendices at the back of the book reveal how much research and passion was put into the project, with over twenty pages detailing the origins of the characters. Details like Medea’s status as a real historical figure and why the creators chose to use anachronisms to tell her story are fascinating. It’s unsurprising to learn that Le Callet is a scholar herself, conducting research in philosophy and literature, and having translated some of Seneca’s work. Peña’s artistic contributions are just as fantastic and though the art isn’t the usual kind that would draw my eye, having more of a traditional comic book style, it kept me engaged throughout with its incredible use of colour and line drawings; from Medea’s bright childhood to dramatically dark adulthood, to the neat contained panels that only fire from torches can traverse, Peña’s light touch brings Medea’s pages to life.

We think that if Medea could see this retelling, every feminist bone in her body would feel fulfilled. A class act from all involved.

Blandine Le Callet (W), Nancy Peña (A), Montana Kane (T) • Dark Horse Comics, $29.99

Review by Lydia Turner