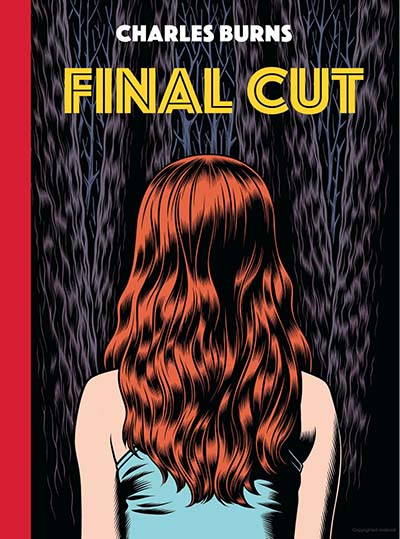

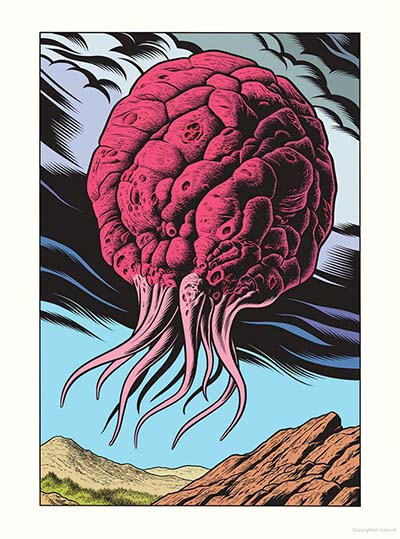

Charles Burns offers his readers no clues. There is no subtitle hinting towards a plot, no description or biography, and nothing to give one an indication of what they are about to plunge into when they pick up his latest book Final Cut. The only thing offered is an opening image of an alien blob floating above a winding road, which reappears at the back with the addition of a solitary female figure. And yet, that is enough because, for almost two decades now, anyone who loves comics knows how well he can spin a tale that involves young people and extraterrestrial lifeforms.

This time around, the youth in question are amateur home-moviemakers Jimmy and Brian, a woman named Laurie who agrees to star in their next film, and her friend Tina. The film is titled ‘Final Cut’ and —much like Black Hole did so many years ago—the only thing we can be sure of is that nothing here is what it appears to be.

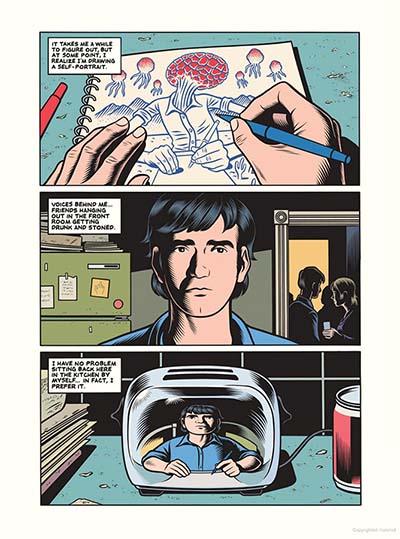

Jimmy seems friendly but shallow with an easygoing charm; Laurie is intrigued by Brian; and Tina has a gregariousness that the others seem to lack. Brian is marked as separate right from the start, when we are introduced to him sketching an alien in someone’s kitchen while a party is in progress. He can’t fit in, but there are sudden shifts of mood when his awkwardness is replaced by something darker and almost ruthless. One is forced, time and again, to recalibrate how each character is perceived, which makes for deliciously unsettling storytelling.

Burns creates strongly delineated characters, in terms of personality, although their faces start to look alike after a while. This may be deliberate; an emphasis on tapping into the collective anxiety of a generation rather than focus on individual features.

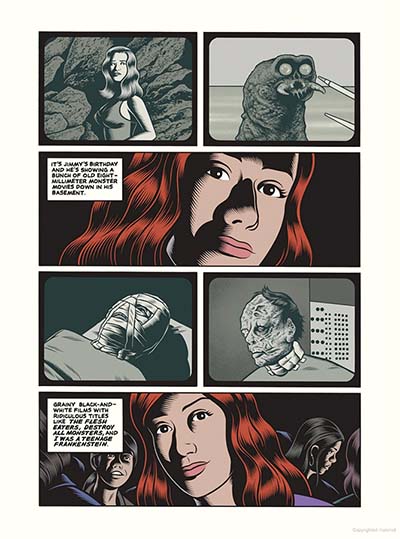

Final Cut is also, on one level, an homage to old Hollywood B-movies, many of which make an appearance — from The Flesh Eaters (1964) and Destroy All Monsters (1968) to I Was A Teenage Frankenstein (1957) and Rodan (1956). Brian asks Laurie out to a screening of sci-fi horror Invasion of the Body Snatchers (presumably the 1956 version that appeared two years after the novel on which it was based), and the experience only serves to confuse Laura further because she can’t quite figure out what he is really like. Including the movie allows Burns to draw from the same well of inspiration though, where interstellar spores mingle with human DNA to create something familiar yet monstrous.

One of the nicest things about this book is how the use of colour allows Burns’ art to shine. There are full-page panels so intricate that they deserve to be framed. It’s also telling how Black Hole was influential enough to instantly mark Burns’ style as distinctive from anyone else working in comics at the time. Every page of Final Cut is testament to his enduring love for the surreal, or just plain weird.

It’s interesting to consider that a lot of B-movies from the 1960s and early 1970s reflected social anxieties brought about not just by the end of a hippie utopian age, but by the knowledge that society was becoming more fragmented. The teenagers who populate Burns’ worlds often share those fears, with disengaged lives and relationships that appear to have little meaning. It’s what makes Final Cut more than just a good old-fashioned horror story. For a book supposedly set in the past, what makes it genuinely frightening is how eerily it reflects our own time.

Charles Burns (W/A) • Penguin Random House/Jonathan Cape,

Review by Lindsay Peirera