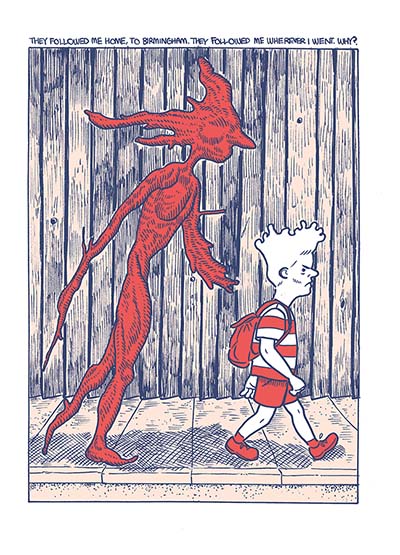

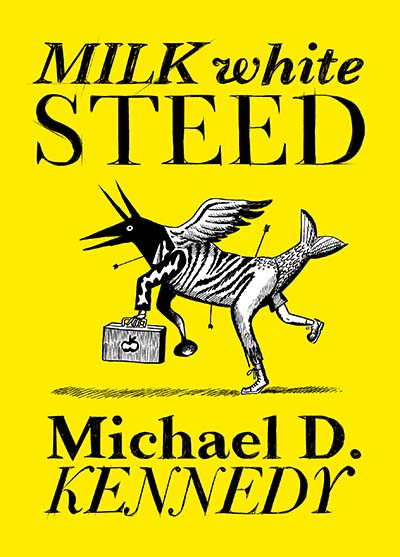

Milk White Steed introduced this reviewer to the existence of the Ligahoo. Also known as Lagahoo or Lugarhou, the mythical shapeshifting monster comes from the folklore of Trinidad and Tobago, and makes its presence felt in a short story about a child on his tricycle. Together with nine other tales, it announces the arrival of a mature illustrator from Birmingham, England.

Britain is home to the second-largest population of Jamaicans living outside of Jamaica, after the United States. Many arrived in the aftermath of World War II to meet the country’s acute labour shortages, and those links between both countries continue to stay strong. It explains why artists continue to find ways and means of expressing how that relationship has evolved. Michael D. Kennedy’s book, then, is part of an old discourse that begins with generations of immigrants asking themselves a deceptively simple question: what is home?

That question becomes a thread that binds these disparate tales together, each branching out in startling, sometimes surreal ways, to try and make sense of West Indian lives in a country far from the land of their ancestors. It’s hard not to recognise Kennedy’s presence in these stories, as an artist of Irish and Caribbean heritage who grew up in small English towns. They form the backdrop of his stories — Coventry and Small Heath, Tamworth and the Tyburn Road, all names and places where the idea of a duppy, or ghost, would seem incongruous. And yet, by placing his West Indian characters in these settings, he raises a point about how their histories are intricately tied to England too.

The book manifests a desire expressed by Kennedy a couple of years ago, in an interview where he was asked about the main influences and inspirations behind his work. He spoke of wanting to provide “a stronger foothold for playful Blackness” in the cartooning industry, and of injecting his own British and West Indian experiences into his work to address a gap in cartooning that had little space for people who looked like him. It also makes sense for that perspective to take the shape of folklore, given how the tradition has always helped develop a sense of identity.

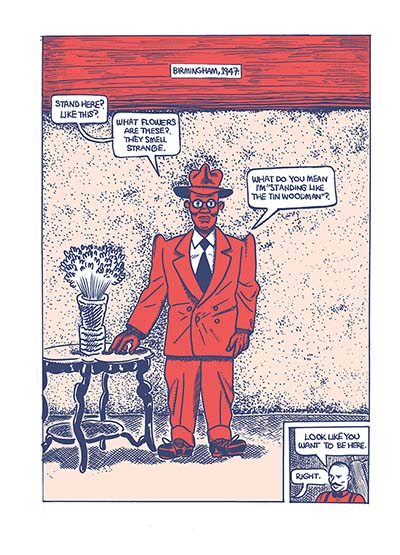

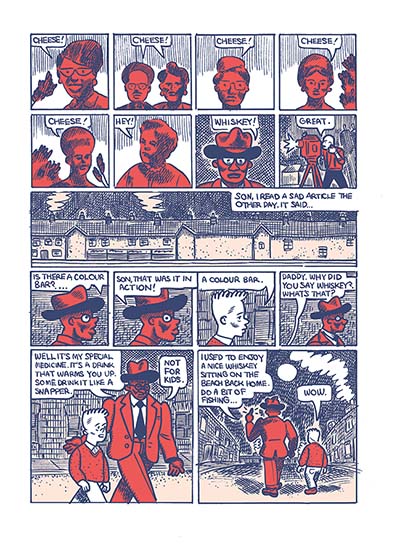

There isn’t a linear approach to storytelling in these pages, and one suspects that Kennedy is often aiming for a mood rather than a moral. His style complements this, each story adopting a dominant tone of red or yellow or green, with the panels sometime resembling woodcuts, and faces often in shadow. There is humour too, but it is undercut by subtle hints about racial tension or rendered tragicomic by focusing on a character’s isolation.

At times, Milk White Steed exhibits elements of magic realism, the postcolonial style that emerged partly because traditional interpretations of the world were deemed inadequate, and partly because the movement’s roots in Latin America were political. Kennedy’s stories do something similar, by imposing something otherworldly upon reality, as if to show that his people occupy two worlds simultaneously.

To read this is to revel in the versatility of comics as a medium and applaud its ability to engage with difficult questions. It may not always make sense at first but, with every reading, something new is revealed.

Michael D. Kennedy • Drawn & Quarterly, $24.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira