In the depths of a secluded forest, a wizened witch lives a solitary life isolated from the outside world. Her reality is about to be disrupted, though, when she discovers a farming community has arrived in her woodland home. With her territory being impinged on, and her self-imposed exile threatened, she takes drastic steps to rid herself of this human blight, performing arcane rituals that will release monstrous forces on the settlers. Her actions will have far-reaching consequences for all concerned however. Not least of which herself…

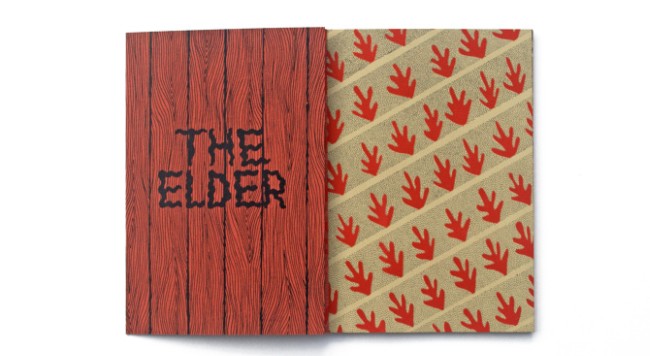

Esther McManus’s The Elder uses the conventions of fairy tale storytelling as the framework for a narrative rich with deeper themes; ones that are contemporary yet ageless. Let’s explore those fantasy trappings to begin with, though, because – on a superficial surface level – The Elder is first and foremost presented in the style of a child’s storybook. It’s an object lesson on the dangers of an irrational fear of the unknown; a visual morality play dressed up as folk tale, appropriating familiar fantastic elements from our childhood reading to symbolise something more profound. Magical spells represent acts of intolerance as the witch attempts to drive the encroaching villagers away. Visitations from grotesque supernatural entities reflect a vulnerable desperation and her inability to cope with the alien.

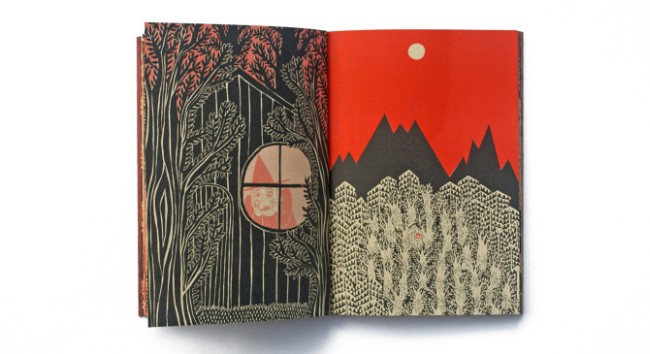

At the centre of this tale is the Elder herself – the character who drives forward events and around whom everything else revolves – a traditional malevolent crone but one who McManus portrays as being as much a victim of herself as any of the villagers she torments. At points she’s almost strangely sympathetic; in one notable scene we observe a close-up of her terrified face in the window of her out-of-the-way cabin before the “camera” zooms out on just how cut off her home is, emphasising just how detached and withdrawn from the warmth of companionship she really is (see image below). This is the tragedy of the piece. That in attempting to rid herself of what her mistrust perceives as an unwanted incursion rather than embracing the potential benefits of this change she is only likely to perpetuate her own miserable subsistence.

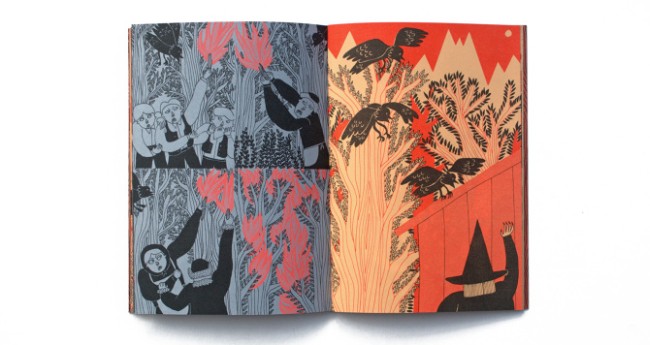

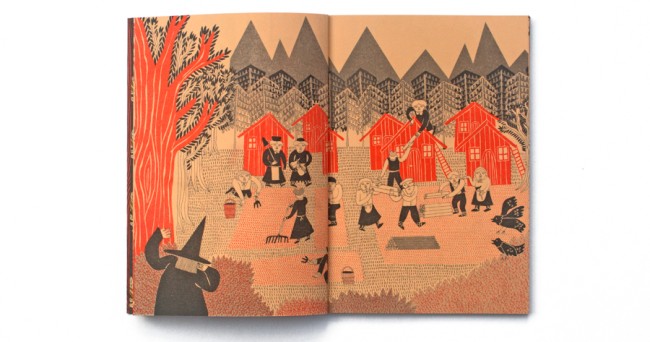

McManus uses a suitably storybook illustrative style throughout, which is busy and detailed and yet, simultaneously, adopts a childlike faux naivety to underscore its folkloric influences. Her deft ability to jump visually from the joyous and celebratory (the early scenes of the farmers) to the dark and sinister (the witch’s nocturnal machinations) owes much to her intelligent choice of colour which plays such a significant part in creating atmosphere and enhancing mood. The rich orange and red hues in certain segments of the story, for example, have an appropriately autumnal Halloween-feel to them. Throughout, there’s a highly effective visual juxtaposition of the eerie, the ominous and the stuff of nightmares with the aforementioned children’s book artistic sensibility. One scene, in particular, gave me a definite Sendak Where the Wild Things Are moment…

McManus uses a suitably storybook illustrative style throughout, which is busy and detailed and yet, simultaneously, adopts a childlike faux naivety to underscore its folkloric influences. Her deft ability to jump visually from the joyous and celebratory (the early scenes of the farmers) to the dark and sinister (the witch’s nocturnal machinations) owes much to her intelligent choice of colour which plays such a significant part in creating atmosphere and enhancing mood. The rich orange and red hues in certain segments of the story, for example, have an appropriately autumnal Halloween-feel to them. Throughout, there’s a highly effective visual juxtaposition of the eerie, the ominous and the stuff of nightmares with the aforementioned children’s book artistic sensibility. One scene, in particular, gave me a definite Sendak Where the Wild Things Are moment…

Told in a largely silent format, occasionally punctuated by expository verse, this handsome risograph produced item has a distinctly Nobrow Press feel to it in terms of both presentation and tactile physicality. With a story that can be appreciated on a number of levels, and is thematically open to multi-layered interpretations, The Elder is a gorgeously presented work that serves as an excellent introduction to Esther McManus’s art.

For more on the work of Esther McManus check her site here. The Elder is available from AE Folklore here priced £18.00.

This completely escaped my attention, looks great!