The issue of sexism and a lack of realistic female role models in super-hero comics is one that has plagued the industry for years. Will Brooker – Professor in Film and Cultural Studies at Kingston University, an academic with a noted interest in Batman, and the first British editor of Cinema Journal – has taken a distinctly proactive approach to the problem.

In collaboration with artists Suze Shore and Sarah Zaidan, Brooker has sought to underline that strong, relatable female characters operating in a world of costumed crusaders can be portrayed without falling back on the clichéd representations so usually associated with mainstream comics. My So-Called Secret Identity is the result of this endeavour – a series that follows the exploits of Catherine Abigail Daniels (Cat), a young would-be super-heroine in Gloria City.

Critically acclaimed by publications like Femina and The Guardian, the first four issues of My So-Called Secret Identity are available to read online here. With the Kickstarter to fund issue #5 in full swing (offering the opportunity to own the entire first five issues in print), and as part of this column’s ongoing series of interviews spotlighting the world of self-publishing, I took the opportunity to talk to Will about creating a super-hero comic for a female audience, reactions to the project to date, and the unique collaborative background to My So-Called Secret Identity…

BROKEN FRONTIER: To begin with could you give the Broken Frontier audience a brief breakdown of My So-Called Secret Identity’s premise and cast of characters?

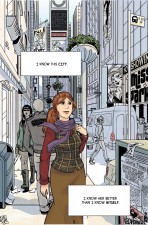

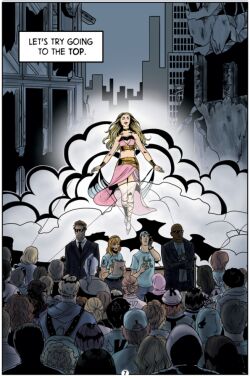

WILL BROOKER: In story terms, the book is about Catherine Abigail Daniels, a young woman in Gloria City. Gloria City is a town full of superheroes, though they never do anything heroic, and nobody is sure if they even have powers beyond dry ice, hydraulics, lighting effects and stunt teams. Catherine, or Cat, has no powers herself. She goes through life insisting she was nothing special, because she’s learned to keep her head down, to never boast or show that she’s different. But by the end of the first episode, she’s been pushed to the edge, and finally snapped: the ‘hero shot’ of this issue shows Cat looking up at us, admitting to the reader and herself that she does have a kind of power. She’s really, really intelligent. And if nobody’s going to take her seriously as Catherine Abigail Daniels, maybe she’s going to have to get a costume, an icon and a brand name, and play the superhero game herself.

WILL BROOKER: In story terms, the book is about Catherine Abigail Daniels, a young woman in Gloria City. Gloria City is a town full of superheroes, though they never do anything heroic, and nobody is sure if they even have powers beyond dry ice, hydraulics, lighting effects and stunt teams. Catherine, or Cat, has no powers herself. She goes through life insisting she was nothing special, because she’s learned to keep her head down, to never boast or show that she’s different. But by the end of the first episode, she’s been pushed to the edge, and finally snapped: the ‘hero shot’ of this issue shows Cat looking up at us, admitting to the reader and herself that she does have a kind of power. She’s really, really intelligent. And if nobody’s going to take her seriously as Catherine Abigail Daniels, maybe she’s going to have to get a costume, an icon and a brand name, and play the superhero game herself.

Cat is our central, viewpoint character. There’s a background cast of larger-than-life, costumed figures, including the Major, Sekhmet, Kyla Flyte and Miss Sparkle, but she doesn’t have much contact with them, any more than you or I would have much contact with Tom Cruise if he was in town promoting a movie. She does cross paths with the Urbanite, the city’s self-appointed armored lawman, and his sidekick the Misper, who becomes a particularly key character. But most of her dealings are with her housemates, Kit and Kay — two fashion students whose relationship seems to defy easy definition — and her landlady (and professional single mom) Dahlia, who becomes a close friend.

BF: Cat was created with a specific aim in mind – to provide a female character operating within the traditions of the super-hero world but devoid of the dubious storytelling trappings that have evolved around female characters in that genre. Why did you decide to take such a proactive approach to the issue?

BROOKER: The overriding sexism and limited representation of women in both comic books and the comic book industry had been bothering me for some time.

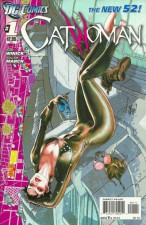

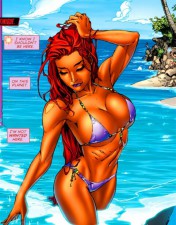

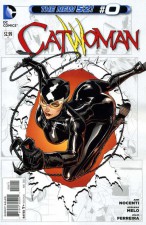

It just came to a head for me one day, soon after the start of DC’s New 52, which seemed particularly full-on with its glossy, almost soft-porn images of Catwoman and Starfire, when I was suddenly struck by the huge gulf between these fictional women and the women I was actually teaching. Not just in terms of how the women in mainstream comics tend to look and act compared to the diversity and intelligence of the student body, but because I was made to feel unwelcome and uncomfortable in the comic shop near my campus, and I couldn’t imagine that most of my female students would want to walk in and browse.

Catwoman and Starfire as depicted in DC’s New 52 comics

You could say that the initial idea behind MSCSI was to bring those two things together — to depict women in the superhero genre who were more like the women I actually work with every day, and to try to create a superhero comic that those women might want to read.

BF: What kind of reactions has My So-Called Secret Identity elicited to date? Has it provoked the kind of discussion about the depiction of women in super-hero comics that you were hoping it would?

BROOKER: Yes, it has. It’s prompted journal articles and academic discussions, and articles in the mainstream media (Femina, The Guardian, Ms Magazine, Stylist) which have reached a wide popular audience. It’s been featured extensively on comic book blogs over the last 18 months or so. I think it’s certainly provoked debate. It’s really achieved far more than I ever thought it would.

Generally though, the response has been overwhelmingly positive, from comics professionals, fans, casual readers, journalists and reviewers. A number of people have said this was what they were waiting for, even if they didn’t realise it; others have said this is the comic they want their daughters to read. I couldn’t really ask for more.

BF: Given the mission statement you had set yourself were there any points in the process of writing MSCSI where you caught yourself inadvertently slipping into the clichés of mainstream comics?

BROOKER: Only early on. I can’t say too much about it as it concerns the events of issues #4 and #5, and the final issue is still forthcoming — it’s one of the main projects we are using the Kickstarter to support.

But in general terms, I had written the physical harming and death of female characters into the story, for no good reason at all except that it was what I was used to in mainstream comics. It’s pretty shocking, with hindsight, how powerful those structures must be, if I fell into them without thinking. I just wrote that plotline because I had a sense that’s ‘how things happen’ in these stories.

Fortunately, someone pointed out what I was doing, and I changed path. That was a key liberating moment in the writing.

BF: The book is full of analogues from the Batman universe with new twists to them. How did they factor in to the comic’s original premise and, given your position as an academic who has written extensively on the Batman mythos, how vital was playing with those toys to you?

BROOKER: In the original, very early premise, MSCSI was a hypothetical pitch based on the idea ‘what if Batgirl had been a Vertigo comic in the 1990s?’ — with all that involves in terms of art style, aesthetic, key characters, storyline and writing. It was Barbara Gordon in a household a bit like the one in Neil Gaiman’s ‘A Game of You’ storyline, with other Vertigo characters as her colleagues and buddies.

Accordingly, of course, Catwoman, Robin and Batman took on different roles, and were going to intersect with this Batgirl origin story.

At a certain point in the process, I realised we could actually make a proper comic out of this idea, and I took the decision to branch out into original territory — original in terms of developing characters from analogues and archetypes, as many other writers have before me.

I still see MSCSI as exploring the tropes and conventions — and the problems and limitations — of the Batman mythos. In that sense, I see it as a kind of theory-as-practice — an extension of my work on Batman, analysing and examining through storytelling rather than through more traditional scholarship. But that’s only on one level. I think MSCSI has its own life and energy, and it stands up independently even if you don’t know anything about Batman.

BF: Suze Shore’s art on MSCSI blends those big, bold super-sequences with a more subtle and character-led visual storytelling. Could you tell us about how you collaborate creatively and how Suze came to be a part of MSCSI?

BROOKER: I simply contacted Suze when I saw her work online — a little cartoon that pointed out the ridiculous outfit worn by Poison Ivy in the Arkham video games. I commissioned some character sketches and costume designs from her, and then more and more artwork as I really loved what she was doing.

So in a sense, she played a key role in creating the world and its characters before we even started to work on MSCSI issue #1. She entirely designed Kyla Flyte, for instance.

When it seemed that a full-length first issue of MSCSI was a genuine prospect, I asked Suze if she’d consider it, and what it would cost, and we went from there.

My scripts are, I think, fairly detailed. I’ve seen far briefer panel descriptions, in Scott Snyder’s and Mark Millar’s work, for instance. (I’ve also seen far more detailed scripts, from Alan Moore.) I give quite a lot of information, from panel layout to ‘shot type’ to mood, character emotion and overall reference (such as a direction that I’d like a particular scene to evoke Tim Sale’s work on Daredevil Yellow and a sense of The Catcher in the Rye, West Side Story and the novel It’s Like This, Cat; in that case I would include visual illustrations).

Suze thumbnails the pages for layout and composition, I approve those, then she works on the black and white line art, sending me each page as it’s completed. I might make some suggestions, which she incorporates. She sometimes makes suggestions to me about lines of dialogue or caption, which I always tend to follow.

Suze thumbnails the pages for layout and composition, I approve those, then she works on the black and white line art, sending me each page as it’s completed. I might make some suggestions, which she incorporates. She sometimes makes suggestions to me about lines of dialogue or caption, which I always tend to follow.

Then the pages go to Sarah, who colours, and adds a great deal in terms of storytelling and again, mood and atmosphere.

I have a visual in my head when I write the script, which I’m essentially trying to convey to Sarah and Suze through words, but as soon as I see the page of artwork, it replaces the picture I had before and becomes my single, authentic point of reference for that scene.

BROKEN FRONTIER: Sarah Zaidan provides segments in MSCSI depicting Cat’s mental processes that are very different in presentation. What extras do you feel Sarah’s digital art brings to the book and its portrayal of Cat’s true super-power – her intellect?

BROOKER: Sarah’s colours on every page shouldn’t be overlooked, even though her MindMaps might be the most obvious and distinctive contribution she makes. If you compare the black and white pages to the finished work, there’s a transformation of Suze’s art (which of course, is great on its own) into a deeper, richer, lived-in world, with more texture and complex light patterns. There’s a scene where Sarah switches, at my suggestion, from the usual watercolour effect to a slicker, digital finish, to evoke the New 52 with its cinematic shine and gloss. So she adds a great deal.

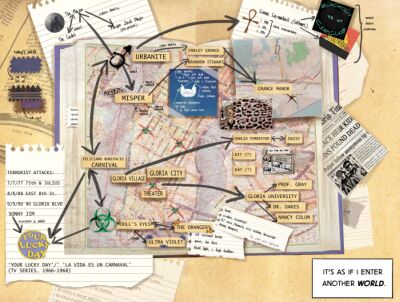

The MindMaps are, I believe, unique in superhero comics. They’re a representation of entering Cat’s mind and seeing how she connects things up, how she structures and makes sense of the world. They show how she retains information in her head — academic notes, ideas about her outfit, memories of her dad, attempts to store the names of people she just met, background knowledge about recent terrorist attacks on the city, a general sense of the celebrity networks and their branded products — and makes links between key elements.

The issue #1 MindMap is more of an overview. The issue #2 feature shows her puzzling over, and figuring out, a discrepancy between the geography of Grange Manor and its depictions in the media, which leads her to investigate it for real. Issue #3 allows us to see how Cat researches and recreates a sense of Connie’s personal history while also working on solving Carnival’s newspaper puzzle, at the same time.

The issue #1 MindMap is more of an overview. The issue #2 feature shows her puzzling over, and figuring out, a discrepancy between the geography of Grange Manor and its depictions in the media, which leads her to investigate it for real. Issue #3 allows us to see how Cat researches and recreates a sense of Connie’s personal history while also working on solving Carnival’s newspaper puzzle, at the same time.

I think they depict a certain kind of intellect — more of a humanities, history, cultural theory, art, philosophy and literature intelligence than science or math. They’re meant to look a little like scrapbooks and a little like essay plans.

BF: It’s not just Cat’s place as strong central lead that marks out MSCSI as providing a positive depiction of female characters. As a team you have also broken the traditional conventions of sexualised costumes for super-heroines. Were “realistic” costumes one of the first items on your checklist for the series? What thinking went into the design of Cat’s more functional look?

BROOKER: Yes, I think they were important from the start. I wanted to convey the idea of a costume that someone in Cat’s position could actually buy, and put together without sewing or construction skills. There’s no way most PhD students in literature and philosophy could tailor an outfit or pay a seamstress to produce a costume; they couldn’t get Kevlar armor or build a helmet, or customise a utility belt. Her outfit is made on a budget from high street stores, plus some of her dad’s old cop gear.

I wanted the sense that she’s a hero anyone can easily become. The outfit is practical and sensible, and it serves the purpose of marking her out as a ‘costumed character’ with a recognisable logo and icon, which is what she wanted, in order to be taken seriously by a culture that celebrates superheroes.

It’s true of course that cosplayers do go to a great deal of effort and manage to closely reproduce superhero costumes, so obviously dressing in a full Batgirl kit isn’t impossible. But Cat’s outfit is the kind of thing a novice cosplayer could easily throw together (especially now we’re offering official MSCSI Cat-logo t-shirts from our website).

So, that was one important aspect of her look. Another was, of course, that we didn’t want to show her in anything unnecessarily or gratuitously revealing. That’s not to say that we will never see Cat wearing fewer clothes — she’s at a swimming pool at the start of Volume 2 — but there’s no reason why she’d go around in a metal bikini or with her jacket unzipped over a bra, when she’s trying to sneak into Urbanite’s base.

So, that was one important aspect of her look. Another was, of course, that we didn’t want to show her in anything unnecessarily or gratuitously revealing. That’s not to say that we will never see Cat wearing fewer clothes — she’s at a swimming pool at the start of Volume 2 — but there’s no reason why she’d go around in a metal bikini or with her jacket unzipped over a bra, when she’s trying to sneak into Urbanite’s base.

Another key aim was to feature outfits that people might actually want to wear. So all of Cat’s outfits, not just the costume, are thoroughly thought-through and designed — from her initial Autumn look to the dress she’s looking at when she shops in issue #2, to the hoodie and sweats she’s adopted in issue #4. Kit, Kay, Dahlia, Sehkmet and Misper’s outfits were also carefully planned, thanks in large part to our great artists, who took a lot of care over these details. We wanted the characters’ clothes to reflect who they were, but also to vary in different scenes (for different circumstances and moods) and to work, in some way, as aspirational. Kit and Kay, in particular, wear outfits you might wish you could buy yourself.

BF: The argument that is always tediously and disturbingly regurgitated every time the unrealistic physical depiction of women in mainstream comics is brought up is that super-heroes represent the “perfect physical form”. Why do you think the populist side of comics is still stuck with these entrenched views in 2014?

BROOKER: Probably because the same people keep saying that: youngish, male, white, straight fans and creators. It might be their ‘perfect physical form’. It is, of course, not everyone’s. Supergirl and Catwoman have a certain look in terms of body and face which is fine — there are women who look like that, in the world, even if they’re mostly lingerie models — but the problem is that so many women in mainstream superhero comics have the same look.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong per se with depicting a character as white, blonde, toned and busty. Kyla Flyte fits that mould. The point is that this is only one type of woman, and we should see many other types in comics, as we do in the real world.

So, the reason those views dominate, I think, is because the loudest and most dominant voices in comics are those of a specific demographic, and they probably think their own opinions are genuinely common sense truth.

Cat’s creative team with a comics-style twist – Will Brooker, Suze Shore and Sarah Zaidan

BF: There’s a greater collaborative background to MSCSI that is quite unique. Was that sense of community and interaction something you were always looking to foster with this project?

BROOKER: Yes, it was. Again, I think that was part of the initial aim to do things differently, and, we hoped, do things better — even if it didn’t work, it would still be different, and still interesting in that respect as a creative experiment.

So that community, collaborative model went along with the deliberate aim of having a predominantly female team. It was a way of exploring an alternative way of working. Also, I felt it matched the central concept of scrapbooking, montage and collage that was always inherent in MSCSI — and importantly, it gives us the sense that there is no one version of Cat (and Dahlia, and Connie, and so on). There is no single definitive look for these characters. In issue #5, we play with this idea a little in terms of infinite earths, but more broadly I think it’s valuable that our characters aren’t tied down visually to a particular face or body, and aren’t tightly owned by a single person. Much of what you see in MSCSI is the result of collaboration: Sarah originally sketched Urbanite from my description, for instance, then Clay Rodery delivered a more realistic, detailed version, and Suze used that as the basis for the character in the comic itself.

On a practical level, that collaboration has meant that MSCSI has been a platform for a number of people to achieve greater publicity, make a bit of money and attract more work, which is obviously a good thing. Many people are able to share in the project’s success, and take advantage of that in their own careers.

BF: Gloria – the fictional city that Cat operates in – has echoes of what James Robinson did with Opal City in Starman. Were you actively looking to make Gloria City something of a character in itself in the pages of MSCSI?

BROOKER: Yes, I think that’s quite a common idea in superhero comics: Gotham is certainly a very powerful presence in the Batman mythos. I haven’t read Starman so there’s no deliberate borrowing there, but what I was aiming for in Cat’s relationship with Gloria was a modification of Batman’s relationship to Gotham. She feels it’s her city, and she knows it, but she sees it more as a big sister or friend rather than something she owns, patrols and defends.

BROOKER: Yes, I think that’s quite a common idea in superhero comics: Gotham is certainly a very powerful presence in the Batman mythos. I haven’t read Starman so there’s no deliberate borrowing there, but what I was aiming for in Cat’s relationship with Gloria was a modification of Batman’s relationship to Gotham. She feels it’s her city, and she knows it, but she sees it more as a big sister or friend rather than something she owns, patrols and defends.

She feels possessive about it because it’s something close to her, something she’s grown up with and grown to know. She doesn’t have that same fierce overview of it that Batman has — significantly, she’s nearly always at ground level, on the street, rather than on the rooftops. She loves it like a favourite book or a song. So you could say it’s a character, but you might as well also just say it’s a place. Places are important. I don’t think we have to elevate them by saying they are like a person. They are their own thing.

BF: There’s currently a Kickstarter campaign to fund the fifth and final issue of the first run of MSCSI. What kind of rewards can backers expect?

BROOKER: Most of the rewards are simply pre-orders: order issue #5 digitally, order the collected edition of issues #1-5, order the deluxe edition with guest art from a range of awesome creators. At higher levels, though, we have some unique merchandise like MSCSI temporary tattoos and nail art and the exclusive Urbanite t-shirt; we also offer limited edition, signed prints of Suze Shore artwork and original watercolours from Jennie Gyllblad. If you want to read the script for Volume 2 issue #1, in its current state, that’s a reward: if you want to appear in, or have your name or band or brand feature in, issue #5, that’s another option. Or you can simply donate to become a sponsor, and have yourself listed as someone who made this project possible.

BF: Issue #5 wraps up the first arc of the story. What hints can you give us for what’s next for Cat and company?

BROOKER: Assuming Volume 2 does happen, which I hope it will, Cat undergoes some changes. She changes her style, her body changes, her outfit changes, her role in the community changes. Dahlia, Daisy, Kit and Kay are still involved in the story, but we focus much more in Volume 2 on Kyla Flyte (actually, two versions of Kyla Flyte) and find out more about her character. Urbanite and Misper step out of the narrative a little, and instead we have new people like Miss Sparkle, Black Light and Quiver, who were only mentioned in Volume 1 — plus some characters who appear entirely out of the blue.

BROOKER: Assuming Volume 2 does happen, which I hope it will, Cat undergoes some changes. She changes her style, her body changes, her outfit changes, her role in the community changes. Dahlia, Daisy, Kit and Kay are still involved in the story, but we focus much more in Volume 2 on Kyla Flyte (actually, two versions of Kyla Flyte) and find out more about her character. Urbanite and Misper step out of the narrative a little, and instead we have new people like Miss Sparkle, Black Light and Quiver, who were only mentioned in Volume 1 — plus some characters who appear entirely out of the blue.

Rather than the Batman mythos and The Killing Joke, this story has elements of a Crisis on Infinite Earths and the social realist Green Arrow/Green Lantern stories of the 1970s, plus a sense of Thelma and Louise road trip. Although Urbanite doesn’t feature so prominently, in a way this arc is all about Carnival, and asks why, ethically, it would be wrong to kill him.

So, there’s a lot there and I’m currently thinking and talking to people about how to get that story out in 2015.

You can find out more about My So-Called Secret Identity on the comic’s comprehensive site here and read the first four issues online here. The Kickstarter campaign can be supported here.