This article was originally published by Tom Whiteley on his excellent Suggested for Mature Readers blog. We are sharing it here to mark the release of the new hardback edition of Zenith: Phase II from 2000 AD.

Trying to recall exactly what we meant, back in our teenage comic-reading days, when we talked about “realism” isn’t easy. It was the vital quality that we looked for; realism meant a comic that was worth bothering with, that was of the present rather than the past, that recognised our maturity as readers. It was the building block of everything that followed.

But what was realism? Certainly it wasn’t the same quality you’d see in prose fiction or in art. No book which featured a man who could fly would be thought realistic. Almost everything we read had just such men. No artist who dashed of page after page of exaggerated, hypermuscled figures could make a claim for realism, but those were the artists we called realistic. We – myself and my small coterie of fellow comics readers, with whom I’m now hardly in touch and one of whom is dead – judged Watchmen to be realistic: grimy, gritty, containing sexual acts and acts of senseless violence.

But what was realism? Certainly it wasn’t the same quality you’d see in prose fiction or in art. No book which featured a man who could fly would be thought realistic. Almost everything we read had just such men. No artist who dashed of page after page of exaggerated, hypermuscled figures could make a claim for realism, but those were the artists we called realistic. We – myself and my small coterie of fellow comics readers, with whom I’m now hardly in touch and one of whom is dead – judged Watchmen to be realistic: grimy, gritty, containing sexual acts and acts of senseless violence.

But while Dave Gibbons’s art is detailed in content, drawing every label on every sweet wrapper, it’s somewhat cartoony in form and doesn’t have the fine hatching that was thought crucial for anyone aspiring to realism, something we ignored at the time. Dark Knight Returns was also judged to be realistic, even though the art is far from anatomically accurate, the violence is self-consciously over the top and sex (or heterosexuality) is all but excised from the work, one kiss between the aging Bruce and Selina all we see. Elektra: Assassin, which we considered on the same level as those two works, is packed with sex and has a priapic alcoholic narrator, but couldn’t be further from reality in its art, however glossy those Sienkiewicz surfaces.

What do those three, and all the others we called realistic, like American Flagg, the Helfer-Sienkiewicz Shadow, Ronin, Blood, Black Orchid, The Question, have in common? What were we identifying? We weren’t just blowing smoke, calling anything we liked realistic. Even those comics that were on the periphery of realism – the Baron/Guice Flash, the Ostrander/Brodowski Firestorm – which today look like any ’80s superhero comic, had something different.

However ineptly named, realism was a quality that existed – the reason you’d still put most of those comics in the broad graphic novel corral today. We just didn’t have the right word for it. What we called realistic was usually innovative in either storytelling, breaking the conventions of caption-narrated morality tales, or in the story told. Anything that subverted the clichés, that still gave us narratives of power and action while going in unexpected directions, counted as realistic. Despite occasional idiocy we were actually reading with decent sophistication.

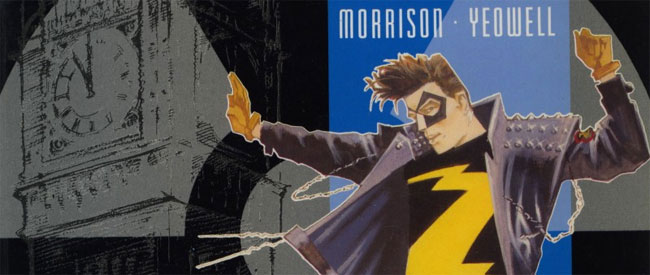

Zenith counted as realistic. That could be put down to two things: Steve Yeowell’s art, which looks as model-posed as anything by Alex Ross, and the story. Grant Morrison was all about subverting the tropes of the superhero. What began in Phase I with the summary dispatch of Red Dragon continues here, with a reimagining of who a wannabe world-conqueror would be and of how he could be defeated.

But before we get onto the main plot of Phase II, there’s other stuff to discuss, namely all the stuff that surrounds and interrupts it. And before we get onto that I should discuss 2000AD a little.

The conventions that governed US superhero comics didn’t apply to 2000AD. Violence was bloody. Stories were never done with in 24 pages; maybe in four, but not in 24. Protagonists weren’t necessarily good. Creative teams generally kept working on the characters or series they created. And finality was a presumption. These series ended. Apart from Judge Dredd, everyone was presumed to have their own capstone. Sometimes that was just the end of a quest, Matt Tallon finally killing everyone who conspired to murder his brother. Sometimes it was death.

So Zenith, unlike most superhero stories, was conceived with an end in sight. But six-page episodes don’t give the writer a lot of time to drop hints about subplots. Walt Simonson could give Surtur a page an issue to develop his apocalyptic profile. If Grant Morrison wanted to do a slow build, to keep his eventual antagonists in plain sight while building their profile and showing how high the stakes were, he had to be more direct.

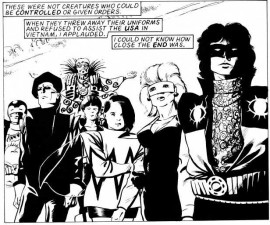

So Phase II begins with a prologue and ends with an epilogue and neither has anything to do with the story – of Zenith learning his origins and defeating a villain – that Phase II is supposedly there to tell. It begins in an art deco Sydney, an alternate universe where Ruby Fox is hanging out with two presumed dead members of her 60s superteam.

Unimpressive in appearance, one resembling Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart in beard and sunglasses and the other with the bob and beret of a French exchange student, they talk their way across the city until a double-page spread – and apart from Judge Dredd, the comic really didn’t do double-page spreads – of a man blowing the head off a tyrannosaur in a sports arena. A classic 2000AD image, sure, but approached in a very contemporary way. With that image the full force of the larger story being told in this series hits the reader, and the final page makes that metaphor explicit. Zenith, in six pages, became about very much more than just Zenith the character.

The sixth chapter of Phase II is another intrusion into the narrative, another foreboding of things to come that makes it clear that the pop star in the leather jacket is destined to be a sideline in his titular series.

The sixth chapter of Phase II is another intrusion into the narrative, another foreboding of things to come that makes it clear that the pop star in the leather jacket is destined to be a sideline in his titular series.

Peter St John dreams of a black sun, a ruined London, of being too late to stop a disaster which has removed humanity from the Earth. He wakes to find Spook, the former teammate we last saw in a beret in Sydney, nude and glittering and floating in the air like Tinkerbell (or the Regency Elf) in his bedroom, making threats. She knows the things he’s pretended not to know. She may even know his plans. There’s a reference to the nuclear threat that this Phase is supposedly about on the last page, but it’s certainly not the source of St John’s dreamed apocalypse. While Zenith strolls into the lion’s den, two chess players are renewing their rivalry.

The last intrusion is the epilogue at Uluru – then still Ayers Rock – where we meet Black Flag for the first time. I’d never heard of Henry Rollins or the phenomenon of American punk back then. In the UK in the late ’80s, you still saw punks – I have a memory of one leering out of a launderette, like a carnival demon, when I was on a march with the Cub Scouts – but they were absolutely over, as over as the Teddy Boys you still saw sometimes.

Still, to have heroes modelled on shaven-headed Buddhists, Sid Vicious or New York rappers was to be light years ahead of other superhero comics. And as a note of doom, the arrival and demise of a speeder from another alternative complete with sexy real science like the Einstein-Rosen bridge worked handily.

Then there are the two interludes. Technically, there are interludes between every Phase of Zenith, but the alternative Maximan and the flashback Mandala ones are drawn by different people for a Sci-Fi Special and a Yearbook and are worthless.

The two interludes that come between Phases I and II, however, are drawn by Yeowell and are vital. The first is a poignant Maximan flashback, fleshing out the first hero and confirming that his life and death were caused by government. The second is about Dr Michael Peyne, creator of all the British superhumans, and not only contains the only ever image of Cloud 9 in costume, it details their birth and the simultaneous birth of a monster, a “storm of shapes speaking in tongues,” that will pop up later, and later again.

So, Zenith. He’s still having pop hits. He’s still arrogant. His musical heart is apparently somewhere else – he’s singing The Smiths’ The Queen Is Dead as he arrives at his Docklands flat (which quotation apparently caused some reprint problems), but he seems to have learned little from his experiences except how to fight.

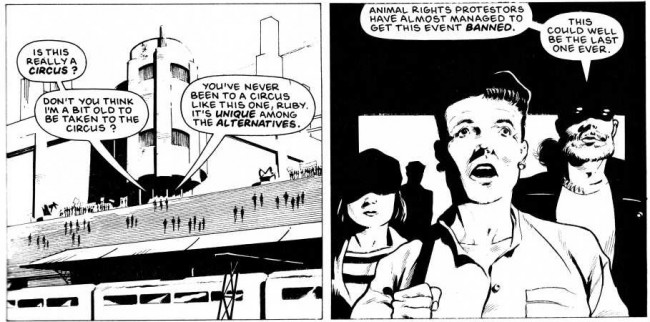

A big, sleek robot called Warhead crashes Zenith’s pad and is getting tidily beaten when a CIA plot-mover called Phaedra takes it out with an epilepsy gun and invites him along to beat up its owner, again with the promise of information about his parents that strung him along last time. They make their way up to the villain’s underground lair in Scotland by way of Zenith’s agent, a commercial flight and a hire car, watched by a pair of flying superhumans the whole time, bemoaning the awful weather.

It’s engaging because of its realism. Rather than Zenith zapping straight up there he travels like any normal person would, and whinges more than most. He doesn’t form any kind of seamless partnership with the CIA agent, nor flirt with her; instead, he openly resents her greater knowledge and continually reminds her of his greater power. Petulant, self-centred and thick, he’s no kind of hero.

But he does beat the villain. The major revisionist element in the story, the transformative element that makes the hackneyed structure it otherwise inhabits new, is Scott Wallace. He’s actually more of a Bond villain than a supervillain: millionaire, secret underground base, threatening the world with nukes, a reluctant genius by his side and facilitating his work. But it’s as if Morrison took those clichéd elements and thought okay, who would this guy really be? Who in the real world wants to rule the world? His answer? Richard Branson.

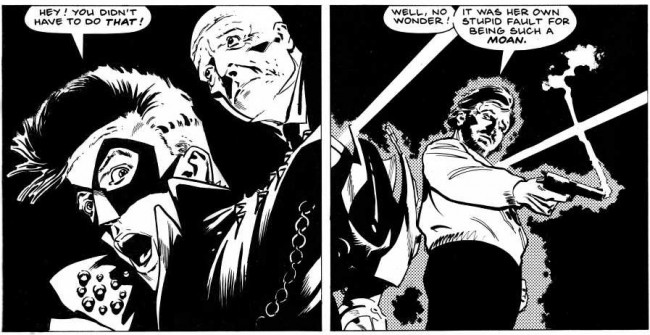

Bearded, wearing a jumper with a hot-air balloon motif, with an attempt to cross the Atlantic behind him, Wallace is unmistakably Branson. But more than that, he’s a wonderful creation. We first meet him watching Zenith’s fight withWarhead, wearing a Comic Relief red nose and sweatshirt.

That hit me with some force at the time. I loved the sheer specific Britishness of it, the idea of this bad guy being one of us. He doesn’t cackle like a monster at the footage – there’s no NYAH-HA-HA – but he’s cheerful and confident of his plan’s success. He doesn’t play the villain, he just is the villain. He wants to take over the world because he thinks he can do a better job. Friendly and open to Zenith, each as shallow as the other, he murders Phaedra without qualm or remorse or any real thought. She’s not part of the plan, so why keep her around?

Zenith, present when his travelling companion is shot, isn’t too bothered either. Peyne even remarks on it, later on, when all their carefully laid plans have gone to shit. He rolls with it and rolls with his new friends: shown to his room, he sarcastically asks for a TV, either determined not to show he’s overwhelmed or actually that stupid.

He stays there, learning about his powers and having sex with Payne’s two silent superpowered creations, Shockwave and Blaze, who followed him from London and presumably rescued Warhead while they were there. And he stays there, not bothering to investigate the line between guest and captive, until Peyne tells him how his parents were killed and reveals that Warhead is actually Dr Beat, the body of his father with the mind all but gone, and that this reanimated monster is going to kill him.

It’s an odd little sequence, down under Schiehallion. If it weren’t for the naturalistic, flowing way that Morrison and Yeowell depict everything, the reader would be asking a bunch of questions. Why would Zenith put up with this? Is it because he’s outmuscled by three superhumans? Is he just not bothered? Does he have a burning interest in his parents? Is he playing dumb or just dumb?

It’s an odd little sequence, down under Schiehallion. If it weren’t for the naturalistic, flowing way that Morrison and Yeowell depict everything, the reader would be asking a bunch of questions. Why would Zenith put up with this? Is it because he’s outmuscled by three superhumans? Is he just not bothered? Does he have a burning interest in his parents? Is he playing dumb or just dumb?

Hilariously, he proves to have accidentally outsmarted his captors by lying to Smash Hits about his birthday in order to spread a rumour that he’s the successor to Elvis, and then kills his father in a lengthy – for 2000AD – slugfest.

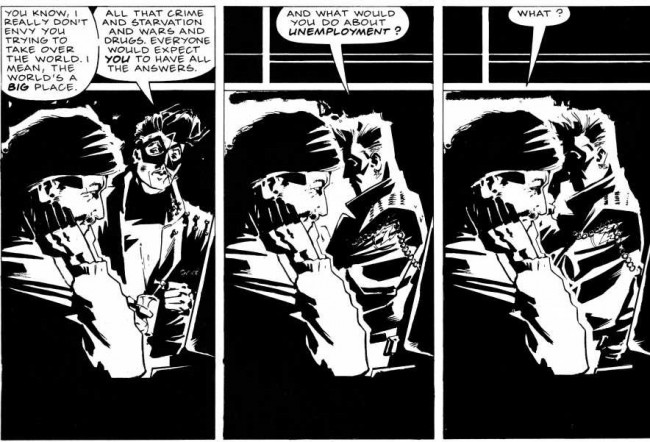

He calls on St John, floating above London in the desperate, egotistical hope that he can to catch two nuclear missiles, to solve a simple riddle and beats Wallace on his own, one superficial intellect understanding another and able to persuade the would-be world-ruler that it isn’t worth the trouble.

It’s a unique solution. Why use force against the guy when you could use realism? Everyone around Zenith thinks he’s vitally important, that his power is the future, that he can own his epoch like Miracleman owns his. But the man himself isn’t bothered. And in, really, the only moment in all four Phases where he bestirs himself enough to do good, he persuades the bad guy that really he shouldn’t be bothered either.

Then it’s home, leaving the villain and all his subplots to themselves, and a final intrusion into the narrative in the shape of Chimera. Freed by the fight, transforming from Scottish agent Eddie to the whole universe in Zenith’s reconstructed flat – and all these closing episodes are exquisitely drawn in harsh blacks and glaring whites as if every scene is spotlit – and finally into something unknowable, a loose end that won’t be picked up for a good while.

But it’s that conversation with Wallace that holds the key to the series. Zenith is in the place where a superhero should be. He’s surrounded by the people and the plots that a superhero contends against. As we’ll see, however, what’s different and realistic about Zenith is that he couldn’t care less.

Grant Morrison (W), Steve Yeowell (A) • 2000 AD/Rebellion, £20, December 2014.

This review has given me cause to re-evaluate my reading of Zenith. Maybe I was not really thinking about the underlying writing, maybe I’m not geared that way, but reading this review has opened my eyes a little more. Great stuff.