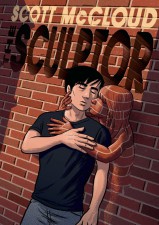

The Sculptor, Scott McCloud’s return from comics theory to narrative, has been greeted with something approaching the city-stopping ticker-tape welcomes once accorded to returning astronauts. However, for all its ambition and achievement, McCloud’s book soon begins to buckle under its own weight.

The sculptor of the title is David Smith, a young man whom we meet on his 26th birthday, in the full throes of his QLC (quarter-life crisis). Having been thrown over by one high-profile patron, he’s now very clearly up against it: after all, who ever heard of an acclaimed artist not having achieved it all by the age of 26?

The sculptor of the title is David Smith, a young man whom we meet on his 26th birthday, in the full throes of his QLC (quarter-life crisis). Having been thrown over by one high-profile patron, he’s now very clearly up against it: after all, who ever heard of an acclaimed artist not having achieved it all by the age of 26?

The book’s first Agent of Change arrives in the unexpected form of David’s Uncle Harry, and its first big turning point comes as David remembers that the last time he saw his uncle, the older man was… dead.

(As well as the first turning point, this also offers the first potential problem for the reader: it’s clear that David is taking arms against a sea of troubles, what with the difficulties of being a white male 20-something artist in NYC, but would he really not remember until several minutes into the conversation that his much-loved relative was actually dead?)

Anyway, once it becomes clear that he isn’t all he appears to be, ‘Uncle Harry’ offers David a classic Faustian pact: the opportunity of a gift that will free up his artistic talent for 200 days, in return for his life at the end of that period.

David takes up the Avuncular Reaper on his offer and gets to work, but his outlook becomes more complicated altogether when he falls in love with Meg, a mercurial jobbing actress who keeps crossing his path. Suddenly, David has something – and someone – to live for…

What follows is a tale of doomed love and artistic struggle, and in those terms, at just shy of 500 pages, it’s easy to see how The Sculptor could loom before the reader as a colossal exemplar of the modern, mainstream-friendly graphic novel.

However, while there’s obviously no questioning McCloud’s sincerity or investment in his work, and his mastery of many aspects of comics storytelling is clear in a number of stunning sequences, it seems to me there’s something missing at the heart of this book. It lacks the subtlety or verisimilitude that made – to pluck a recent example from the air – The Lovebunglers such an immersive and involving piece of work that I could hardly breathe as I entered its last few pages.

McCloud bets the farm on us investing our all in the central relationship, but, sadly, David and Meg are no Maggie and Ray. For all their heat and light, the bluster of the characters’ gestures and outbursts doesn’t seem to be backed up by matching emotional resonance.

This gap is embodied in David’s own emotional immaturity. In his eagerness to tell Meg that he loves her after a couple of encounters, his ardour seems to have more in common with an adolescent’s holiday romance than The Greatest Love Story Ever Told. And despite his protestations, there is something a bit creepy about the way he objectifies Meg in his sculptures – as exemplified on the book’s awkward, troubling cover.

His artistic development seems equally immature, despite what we’re told about his earlier success. He spends lot of time in classic ‘tortured artist’ pose, head in hands, but it’s never articulated that clearly what his artistic vision is. When he embarks on a series of ‘street art’ interventions across the city, he comes up with the sort of imagery that makes Banksy look like a master of subtlety and subtext.

His artistic development seems equally immature, despite what we’re told about his earlier success. He spends lot of time in classic ‘tortured artist’ pose, head in hands, but it’s never articulated that clearly what his artistic vision is. When he embarks on a series of ‘street art’ interventions across the city, he comes up with the sort of imagery that makes Banksy look like a master of subtlety and subtext.

And while he pontificates earnestly about absolutes and his place in the ages, his focus still seems to remain on the short-term goals of the NYC art circus. (That, at least, provides the basis for a few – gentle – satirical swipes at the critics, collectors and gallery gatekeepers locked in an eternal struggle for influence.)

However, the spine of the book is the troubled relationship between David and Meg. And too often in The Sculptor, it feels that we’re being told – shouted at, even – that we should be sharing a profound emotional experience.

However, the spine of the book is the troubled relationship between David and Meg. And too often in The Sculptor, it feels that we’re being told – shouted at, even – that we should be sharing a profound emotional experience.

Rather than flowing naturally from our recognition and involvement with the characters, it seems that our required response is being manipulated by contrived circumstances. And down that path of unearned emotion, sentimentality lies…

In fact, we don’t have to get too far into the book before we’re regaled with the tragic recent history of David’s immediate family. While McCloud narrates the events in an aesthetically pleasing mosaic of moments and memories, it becomes an almost comical run of misfortune that would make even Dickens blush.

There’s clearly – and deservedly – a vast reservoir of goodwill towards Scott McCloud, and I read The Sculptor three times in the hope that I’d have a Damascene revelation of what other reviewers have seen in it. But for all its achievement, it’s ultimately let down by blunt characterisation in service of a trite carpe diem theme that never finds a concrete expression beyond utterances such as “Every minute is an ocean… Let them in… Let them all in…”

To earn the Instant Classic status that has been widely bestowed on it, The Sculptor needs to go toe-to-toe with the very best that this art form – and others – has to offer. And in that company, for all its technical virtuosity, it comes up short.

Scott McCloud (W/A) • First Second Books, $29.99, February 2015.