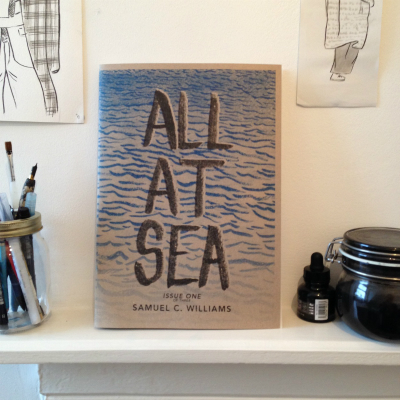

In All at Sea #1 – the first instalment of a three-part drama – creator Samuel C. Williams explores themes surrounding one of the most profound rites of passage in life, the death of a parent. His protagonist Patrick’s relationship with that particular progenitor – his father – isn’t exactly strained but it is portrayed as a slightly uncomfortable one. Their lack of connection as father and son symbolised by the years-long game of chess by phone that the two have been playing. There’s a sensation here of two people struggling to keep the familial bond intact; clinging to an attachment that they both know now goes no further than shared genes.

In All at Sea #1 – the first instalment of a three-part drama – creator Samuel C. Williams explores themes surrounding one of the most profound rites of passage in life, the death of a parent. His protagonist Patrick’s relationship with that particular progenitor – his father – isn’t exactly strained but it is portrayed as a slightly uncomfortable one. Their lack of connection as father and son symbolised by the years-long game of chess by phone that the two have been playing. There’s a sensation here of two people struggling to keep the familial bond intact; clinging to an attachment that they both know now goes no further than shared genes.

When Patrick gets a phone call informing him of his father’s death he returns to his home town for the first time in many years, immersing himself in familiar locales and catching up with old mates. Family friends and locals advise Patrick and his mother not to view his father’s body and to remember him “the way he was”.

When Patrick gets a phone call informing him of his father’s death he returns to his home town for the first time in many years, immersing himself in familiar locales and catching up with old mates. Family friends and locals advise Patrick and his mother not to view his father’s body and to remember him “the way he was”.

But the withdrawn writer begins to have misgivings, fearing that something is not right about the entire scenario. Did his father really die peacefully in his slumber or is there more to his demise than that? And just how far will he go to prove his suspicions are correct?

To describe All at Sea as being a comic that is fundamentally about loss would be accurate but the sense of grief and displacement in these pages is far deeper than just the bereavement that sits at the book’s emotional core. What Williams examines as Patrick returns to the family home is that idea of an inevitable detachment from so many aspects of the things that shaped us; whether that be the friends we leave behind, the childhood memories that seem at once so tangible and yet also so distant, or that environment that was once so comforting but now seems so alien.

This first issue is essentially setting up the premise of the book and whether Williams intends this to be a twisting tale of conspiracy and mystery, or something far subtler, remains to be seen at this juncture. While his visuals are certainly not elaborate his articulate panel-to-panel storytelling complements the tone of the story with a sensitive eloquence – unassuming yet pensive, and able to expressively communicate Patrick’s sense of weary resignation on his return with a delicate minimalism and deft pacing. Just check out the scene where he enters his childhood bedroom – still looking just as it did when he last left it – for evidence of that. The blue-hued riso pages also play a major role here; their melancholy monotone enveloping the reader in an ever compressing cocoon of atmospheric tension.

If I have one main criticism of this opening issue it’s that, to an extent, the very fact that All at Sea is such an understated and subdued piece of storytelling means that a serial comic is probably not the best format for it. There’s not enough of a hook to pull in the casual reader at this moment and I do wonder whether it would engage with its audience more as a complete one-shot. But such, I fear, are the restrictions of self-publishing.

If I have one main criticism of this opening issue it’s that, to an extent, the very fact that All at Sea is such an understated and subdued piece of storytelling means that a serial comic is probably not the best format for it. There’s not enough of a hook to pull in the casual reader at this moment and I do wonder whether it would engage with its audience more as a complete one-shot. But such, I fear, are the restrictions of self-publishing.

As with any multi-chapter drama a full and valid assessment of the comic on solely narrative grounds needs to wait until that vital concluding episode. All at Sea #1 impressed me with its quiet and layered storytelling, though. There’s an emotional depth here that is cleverly underplayed and has me intrigued as to what thematic avenues Williams will take his story down next.

For more on the work of Samuel C. Williams check out his website here. You can buy copies of All at Sea from his online store here priced £3.50.