One of the most eagerly awaited publications of the year, the latest edition of Lose, Michael DeForge’s annual anthology from Koyama Press, doesn’t disappoint.

Michael DeForge’s career so far epitomises what makes comics such a perfect vehicle for self-expression: the power it gives the artist to create a unique and immersive little universe where their own rules apply.

Michael DeForge’s career so far epitomises what makes comics such a perfect vehicle for self-expression: the power it gives the artist to create a unique and immersive little universe where their own rules apply.

However, the latest issue of Lose – DeForge’s annual anthology/’comics laboratory’ – shows that beyond the trippy non-sequiturs and stylistic flourishes, his work is underpinned by sharply observed real-life concerns. The first all-colour issue of the series, it comprises three self-contained stories: two shorter, untitled pieces bookending a 35-page ‘main feature’, ‘Movie Star’.

The first story is a strange and typically dream-like look at the make-believe world of two children – although, characteristically for DeForge’s work, fantasy and reality blend freely into each other.

In its opening scene, coded as if it’s being filmed on a phone, the main character is urged by an unseen companion to transform herself from a smiley child into a swollen-headed, sweaty avatar of rage.

As she takes on the role of the increasingly exasperated ‘mom’ in their game, it’s hard not to see the five-pager as a sharp little take on the painful contrast between childhood and adulthood. (“Beep beep! Make way for my adult body”!)

The theme of parent/child relationships and the transition into adulthood is also present in ‘Movie Star’ – the story of a difficult relationship between a grouchy ailing father and the daughter who cares for him, which takes a trip into Tales of the Unexpected territory when they uncover a fortuitous family connection.

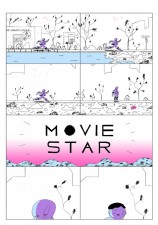

I haven’t dug through the cartoonist’s back catalogue for a while, but I can’t remember many of his other stories being told fairly objectively in something like a recognisable real world. However, as you’d expect, this is definitely naturalism with DeForegean characteristics.

Even in this fairly ‘straight’ tale of family dynamics, the cartoonist uses awkward perpendicular staging and flattened, almost two-dimensional side-on shots. Locked in a Frank Santoro-style 4×2 grid, Kim and her dad tend to be pushed into a limited space in the middle of the frame. The noticeably small lettering heightens the distancing effect.

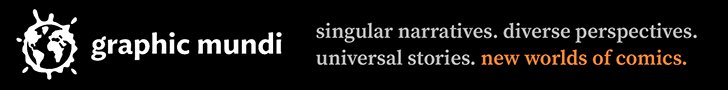

The final nine-page story seems to get back into classic DeForge territory, with the story of “a boy who is also a bird”. However, his glum outlook – “Of all the things to be, what a dumb thing I am” – also has clear metaphorical echoes of the isolation and exclusion you can feel as an adolescent (and beyond) when you’re not sure of your place in the world.

With “boys’ activities” largely defined as smoking joints and squeezing breasts, the strange feathery humanoid bemoans his lot: “Overall, I would say my life is very bad”. He fantasises about having a relationship and children with a familiar ornithologist, but ultimately allows self-harming gloom to engulf him.

In a few short years Michael DeForge has established himself as an artist of unique vision and fecund imagination. Work such as these short stories and First Year Healthy, published earlier in the year by Drawn & Quarterly, suggests that he’s entering an even more relevant and rewarding stage of his career.

Michael DeForge (W/A) • Koyama Press, $10