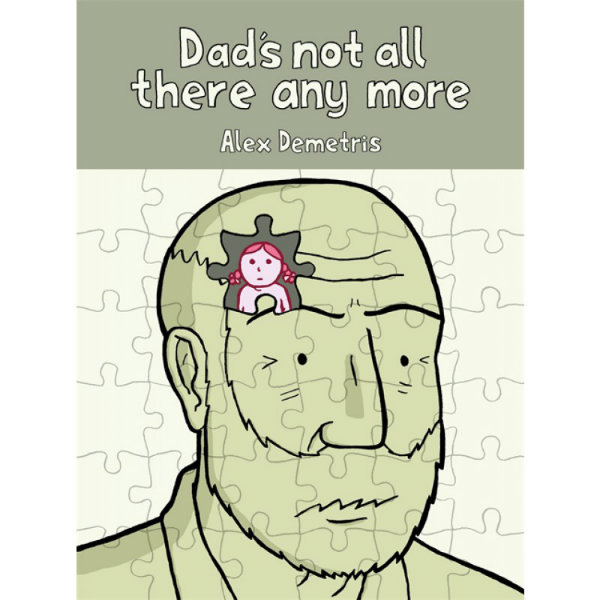

First self-published in 2012, this wonderful example of the power and appeal of graphic medicine started life as an art school project. Since then, Demetris’s intimate account of his father’s struggle with Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) has helped to raise awareness of this mysterious illness.

Dementia scares the shit out of me. I love my brain. The thought of losing my faculties, in any way, to any degree, fills me with dread. Before he died, my grandfather suffered from dementia, though I couldn’t tell you the cause; Alzheimer’s, I think.

Dementia scares the shit out of me. I love my brain. The thought of losing my faculties, in any way, to any degree, fills me with dread. Before he died, my grandfather suffered from dementia, though I couldn’t tell you the cause; Alzheimer’s, I think.

At the end, a man who once possessed a fierce intellect – who loved to read and debate politics and tell stories about how he bumbled his way through World War Two – found himself lost in time, unable to read anything longer than a few paragraphs. He could no longer be trusted to go out alone. Often, he acted like the spoiled teenager who, by all accounts, he never was allowed to be while growing up.

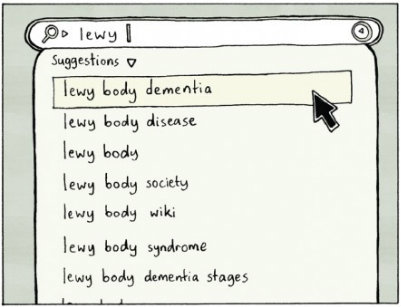

I had a frame of reference then, albeit slight, when I read Dad’s Not All There Any More, by Alex Demetris. LBD is one of those conditions that isn’t quite “sexy” enough to warrant a celebrity spokesperson or its own ribbon (at least, not as far as I’m aware). That might change somewhat (or not) with the post-mortem diagnosis of Robin Williams, but in the meantime, LBD tends to fly under the radar for most of the general population.

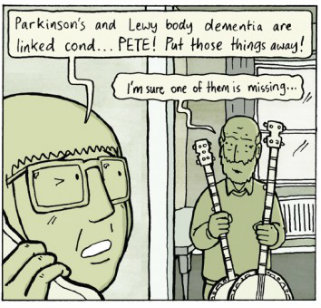

Demetris’s fictionalized account of his family’s experiences with LBD follows a young man named John, whose father, Pete, suffers from the disease. After an initial diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, the family soon learns that Peter’s increasingly frightening mental lapses are due to Lewy Body Dementia.

As his father descends further into dementia, his memory failing, his perceptions of questionable accuracy, John and his family are forced to adapt to Pete’s ever-changing needs. Pete’s once razor-sharp mind is reduced to that of a child. Dependent on his wife Sue and his son for virtually every facet of his life, Pete’s frustration grows in almost direct proportion to his loss of freedom.

What’s most impressive about Demetris’s story is the family’s reaction to Pete’s increasing dependency. Rather than descending into bitterness and despair, John and his mom rally around Pete, doing everything in their power to maintain a decent quality of life for him. Perhaps this is to be expected, but we’ve all heard stories to the contrary.

That isn’t to say that both mother and son don’t have their moments of frustration or despair. Demetris’s portrayal of Sue and John is layered with emotional depth. It’s the honesty and directness with which they respond to Pete’s battle with LBD that is most revealing.

That isn’t to say that both mother and son don’t have their moments of frustration or despair. Demetris’s portrayal of Sue and John is layered with emotional depth. It’s the honesty and directness with which they respond to Pete’s battle with LBD that is most revealing.

At times, the depiction of John’s experiences is unflinchingly painful and frightening. At others, it’s so damn funny, you’ll laugh out loud. It’s this juxtaposition between heartbreaking and heartwarming that makes the book so endearing. Demetris employs a restraint in his storytelling that many creators never attain, striking a subtle balance between illuminating painful truths and then finding the humour in them. It’s a remarkable feat for a young creator.

But that’s not the only thing that’s remarkable about this book. Demetris’s storytelling approach displays a maturity and comprehension of the medium’s unique mechanics far beyond his years of experience would suggest. Clean, bold lines and subtle colour choices combine to create a pleasing visual tone that services the story without sacrificing style.

Particularly striking is the way Demetris uses a puzzle motif to represent LBD’s tendency to chip away at its victim’s sense of self, not to

Particularly striking is the way Demetris uses a puzzle motif to represent LBD’s tendency to chip away at its victim’s sense of self, not to

mention the gaps in our understanding of the disease. Woven into both the book’s structure and its narrative, the puzzle serves as a subtle reminder of just how much victims and their families lose to this mysterious illness.

It’s hard to put a name to a brain disorder like LBD. In our ignorance, we call it a condition or a sickness or a syndrome. We come up with a handy acronym to syphon its potency. How do we begin to talk about such a frightening disease, when most of us don’t even know how to refer to it properly?

This is the value of comics like Dad’s Not All There Any More. When they’re done well, works of graphic medicine, whatever their contribution to comics, transcend the medium, striving to educate and heal, even as they entertain.

Alex Demetris (W/A) • Singing Dragon, £7.99.

The Singing Dragon launch is at London’s Gosh! Comics this Friday February 5th. Details below.