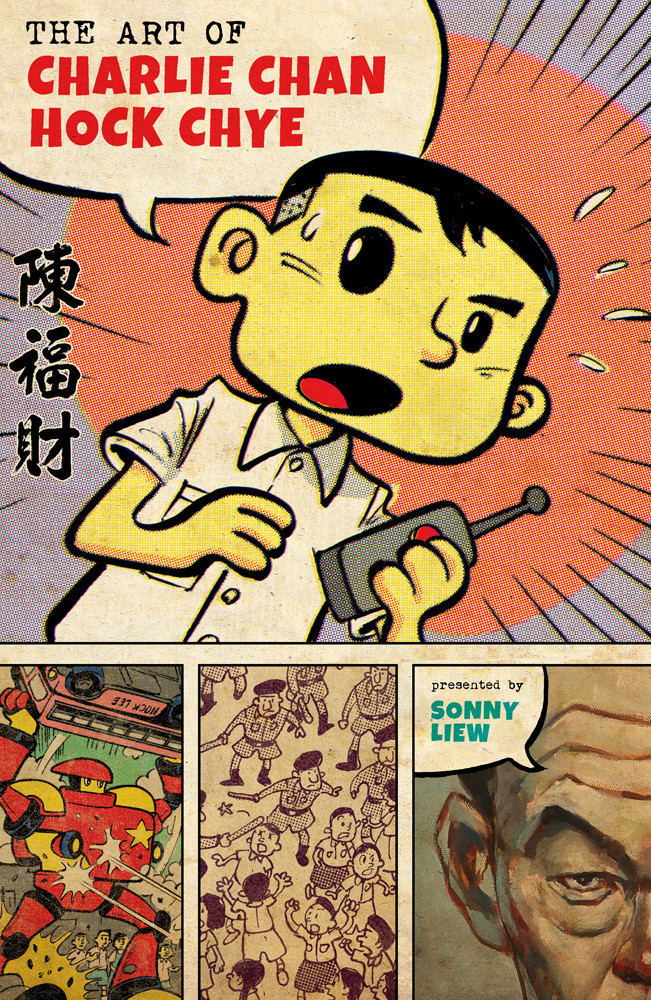

Sonny Liew’s presentation of the life and work of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, an overlooked (fictional) Singaporean cartoonist, is a stunning amalgamation of history, politics, character and art.

The name Charlie Chan Hock Chye might already ring a bell to a few readers out there: ‘Geylang Hill’, his brief memoir comic about growing up in Singapore, appeared in the third volume of Liquid City, an anthology of South-east Asian comics that we reviewed back in 2014

However, most readers won’t have heard of the veteran cartoonist – primarily because he’s a creation of the artist Sonny Liew. And in a stunning achievement, Liew uses Chan’s fictional life story to create several books in one: a political history of Singapore over 70 tumultuous years, from an outpost of the British empire to an economically thriving but tightly controlled city-state; the biography of a comics artist, facing the familiar struggles of making a living and finding and maintaining a voice; and a fantastic act of creative mimicry, following Chan’s work from his teens to his 70s, across more than half a century of comics influences.

However, most readers won’t have heard of the veteran cartoonist – primarily because he’s a creation of the artist Sonny Liew. And in a stunning achievement, Liew uses Chan’s fictional life story to create several books in one: a political history of Singapore over 70 tumultuous years, from an outpost of the British empire to an economically thriving but tightly controlled city-state; the biography of a comics artist, facing the familiar struggles of making a living and finding and maintaining a voice; and a fantastic act of creative mimicry, following Chan’s work from his teens to his 70s, across more than half a century of comics influences.

These threads are woven together with skill and vision. Each of Chan’s major comics projects owes a lot to outside influences, but Liew manages not only to mimic precisely the style of the comics under examination, but also to use these comics to make pointed comments about the situation in Singapore at the time of their creation.

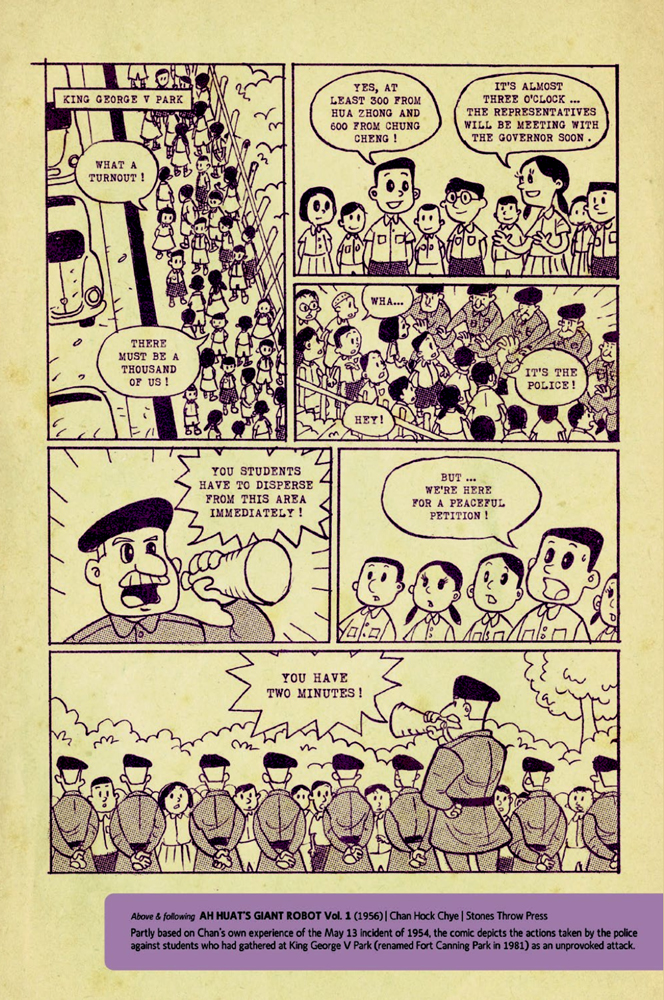

So Chan’s earliest published work, Ah Huat’s Giant Robot (1956), produced when the artist was 18, is ostensibly a boy-and-his-robot story. However, it also refers to Chan’s participation in student protests against British rule two years earlier, as well as the Hock Lee Bus Strike – a bitter industrial dispute that left four dead.

The set-up, in which a young boy discovers a robot that will only respond to instructions issued in Chinese, is also a commentary on the privilege enjoyed by earlier Chinese immigrants who learned English – the imperial lingua franca – over later arrivals who only spoke their native dialects.

(L-R), Ah Huat’s Giant Robot, Force 136 and Invasion

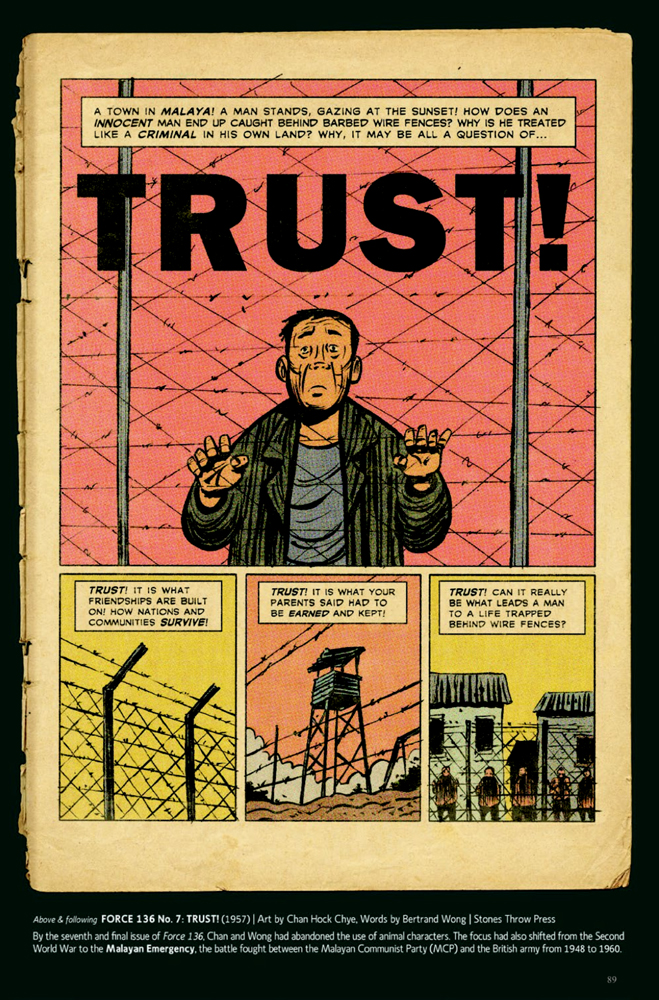

In the same year, Chen and his writing collaborator Bertrand Wong also started to produce Force 136, an anthropomorphic look back at the events of the second world war, which depicted the local Chinese as cats, the invading Japanese as dogs and the colonising British as monkeys (drawing on a popular local song).

However the comic soon leaves behind its funny-animal roots to develop into an altogether harsher treatment of war and its consequences, influenced by the EC war comics of Harvey Kurtzman.

Chan and Wong’s next project was Invasion (1957), a sci-fi epic intended to emulate the more realistic style of Frank Hampson’s Dan Dare, and conceived as the lead story in a comic called Dragon, itself modelled heavily on the Eagle.

Again, the political subtext of the story isn’t hard to pick up, as the citizens of Lunar City seek independence from an invading alien race, the Hegemons. It even features Lee Kuan Yew, who later served as the founding prime minister of Singapore, from independence in 1965 to 1991.

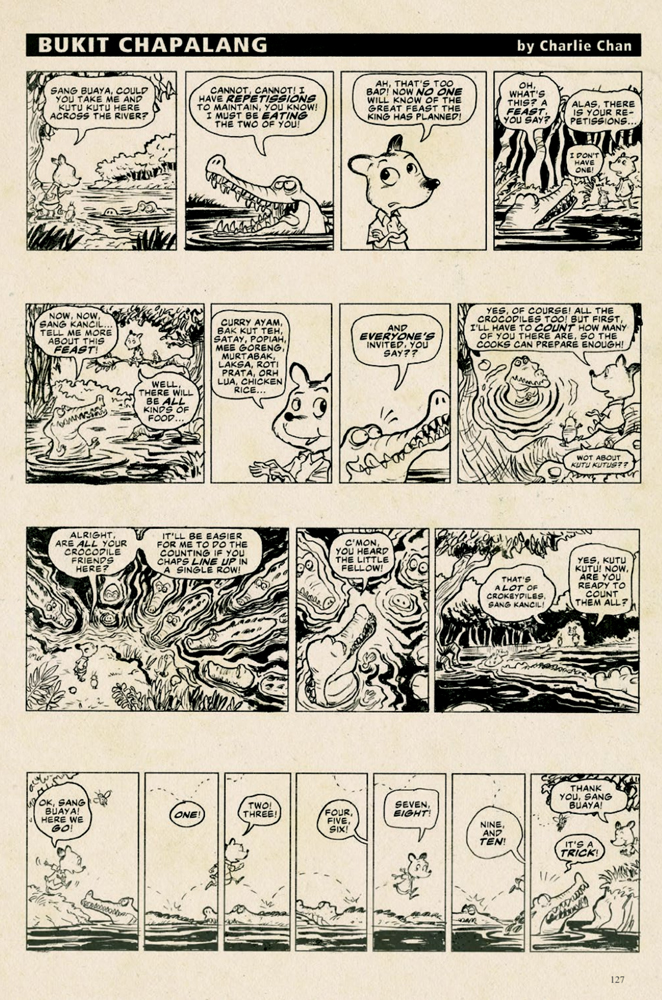

Other comics formats serve other purposes, as events move swiftly on. Singapore’s ill-fated merger with neighbouring Malaysia between 1963 and 1965 is covered in Bukit Chapalang, which starts off as a retelling of local folk tales but soon develops into a political allegory, with real-world figures given animal avatars (led by Lee as the trickster mouse-deer Sang Kancil). In a strip filled with linguistic misfiring inspired by Walt Kelly’s Pogo, the quest for independence is represented by the animals’ desire to have a picnic.

L-R: Bukit Chapalang, Sinkapor Inks, Days of August

However, after minor success with a superhero title, Roachman (1959), again marrying a familiar comic form with particular local concerns, Chan’s career starts to stagnate – especially when his creative partner Wong leaves to take regular employment in order to provide for his young family. After an unsuccessful venture into commercial illustration, Chan takes a job as a nightwatchman, setting up a mobile studio in his office and continuing his creative work there.

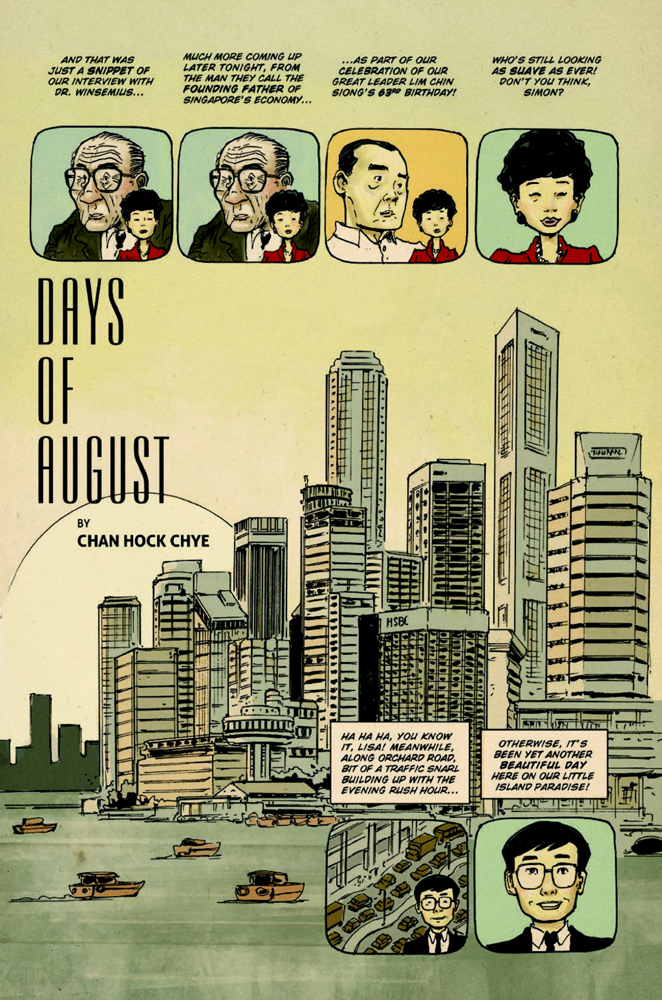

While Chan’s career might have languished at this time, the development of Singapore certainly didn’t. However, while Lee and his People’s Action Party oversaw the ‘economic miracle’ of Singapore’s emergence as a leading financial marketplace, the government ruthlessly suppressed any dissent, exerting control over the media and justifying draconian crackdowns (including detention without trial) by citing the nascent state’s vulnerability and the need for ‘harmony’.

By the 1980s Lee had been transformed in Chan’s work from the heroic advocate in Invasion to the tyrannical manager ‘Mr Hairily’ of Sinkapor Inks – an altogether more downbeat satire representing the country as an office, ruled by quixotic bureaucracy and repression.

(And even though Lee died last year, at the age of 91, his legacy doesn’t seem ready to fade just yet. Indeed, Singapore’s National Arts Council last year withdrew a publishing grant in support of Liew’s book, stating that “The retelling of Singapore’s history in the work potentially undermines the authority or legitimacy of the Government and its public institutions”.)

At 320 pages, there’s much more to this book than even a interminable review like this could do justice to, including Chan’s sketches and paintings, the disappointment of his only trip to San Diego Comic Con in 1988 (“I remained an outsider looking in, unable to become a member of the club, no matter how much I longed to”) and a look at his late major work, Days of August, which mashes up Philip K Dick’s The Man in the High Castle with Miller and Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, to produce a vivid and imaginative vision of how differently Singapore’s history could have turned out.

It’s an adjective that has lost a lot of its heft these days, but in its marriage of form and substance, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye is literally an awesome achievement. It’s a hymn to how comics can reflect the world and how an artist’s vision and compulsion to create can endure, despite a lifetime of public indifference and disappointment.

Sonny Liew (W/A) • Pantheon Books, US$30