Dan Abnett and Broken Frontier Anthology contributor INJ Culbard have a history of genre-busting collaborations, ranging from the anthropomorphic alien invasion of Wild’s End (Boom!) to the post-Victorian zombie allegory of The New Deadwardians (Vertigo). Their newest partnership is no exception.

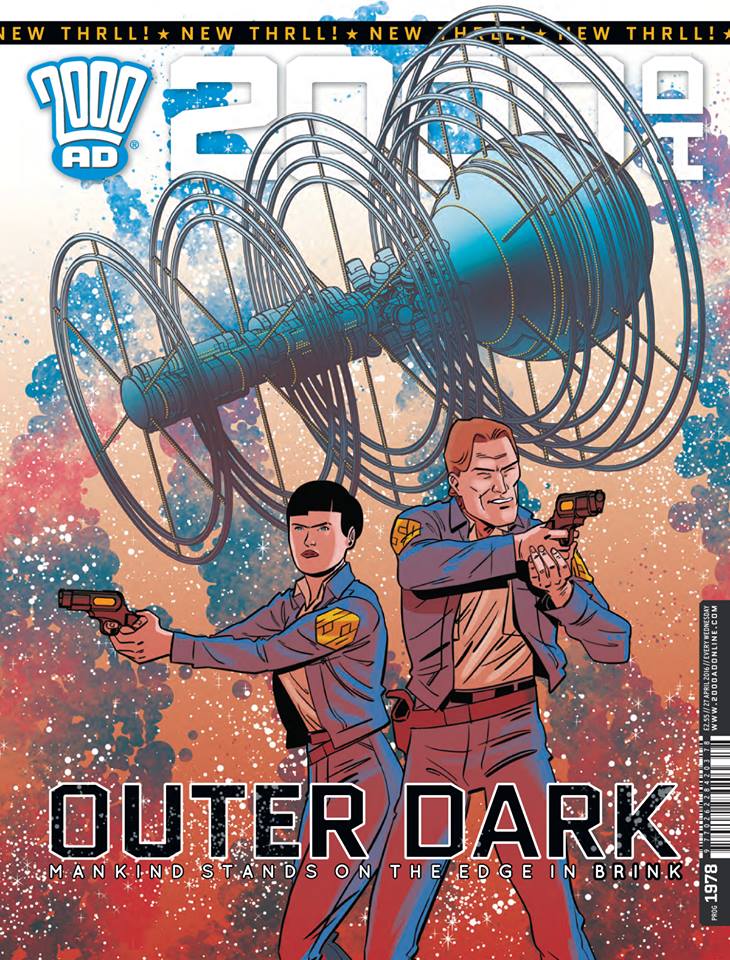

The hard-SF cop drama Brink premiered in 2000 AD Prog 1978 in April. I spoke with script droid Abnett and art droid Culbard via email to learn more about their working relationship, the origins of the project, and grounding the series’ far-future setting.

BROKEN FRONTIER: While you two are frequent collaborators, each of your projects feels fresh and unique. Can you tell us a little bit about the genesis of Brink?

IAN: The ideas we come up with tend to start life as inklings, the sorts of ideas you jot down on a scrap of paper and save for later. The “wouldn’t it be cool if a scientist digging inside the crater left by the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs discovered an alien life form” idea, and you maybe tucked that away in a drawer somewhere.

We have these long telephone conversations we call “omelette sessions” in which we throw in ideas like that and it spirals from there. We fire “what if” back and forth at one another till we’ve got something worth doing. And that “what if” continues well into actual production too.

We have these long telephone conversations we call “omelette sessions” in which we throw in ideas like that and it spirals from there. We fire “what if” back and forth at one another till we’ve got something worth doing. And that “what if” continues well into actual production too.

The world-building is a mix of writing and drawing, so stuff like the ambi-grav and zero-G crime scene start life as an artistic choice but then become part of the writing, and vice versa. And all the while we’re setting parameters, and those parameters inform the design and so on.

What’s really beneficial about working this way is that you’ve got two heads working on one problem, seeing the same thing in different lights and always adding something new and unexpected to the process, till that inkling becomes something exciting. And so Brink itself is just the surface detail of a much, much bigger story, at the heart of which lies the inkling that started it all.

DAN: Ideas can basically come out of nowhere. When you get on well and enjoy enthusiastic conversations, odd pieces of alchemy happen. We might come to a chat with an idea each, and by the end of the conversation a third idea, utterly different to the ones we started with, has grown out of nowhere, simply as a by-product of the discussion about the original notions. And that third idea is probably something neither one of us would have conceived alone.

Brink was a little like that. I can’t remember what we were talking about when the conversation began, but it wasn’t Brink.

Brink has been pitched as “True Detective set in space.” Did you look to any other influences during the development of this series?

DAN: That’s only a label that got attached after Brink was up and running. Inevitably, there’s all sorts of things in there. The trick is, I think, to use references and inspirations as “pit props” along the way, until we both thoroughly understand the tone and flavour each one of us is trying to achieve, and then go back and make sure we’ve made those concepts sufficiently our own.

DAN: That’s only a label that got attached after Brink was up and running. Inevitably, there’s all sorts of things in there. The trick is, I think, to use references and inspirations as “pit props” along the way, until we both thoroughly understand the tone and flavour each one of us is trying to achieve, and then go back and make sure we’ve made those concepts sufficiently our own.

True Detective was a useful shorthand, as was Outland: Outland for the lo-fi reality we were trying to achieve, True Detective for the sense of dropping right in without heavy exposition and just unfolding as we went, through tight, uncompromised character and dialogue. Our idea was to try and make the setting “real” (despite its obvious SF unreality) and then thread in a disturbing sense of something other.

Not many series shift from the claustrophobic setting of an interrogation cell to the boundless expanses of deep space. Did you find any challenges to making the world of Brink feel cohesive and whole?

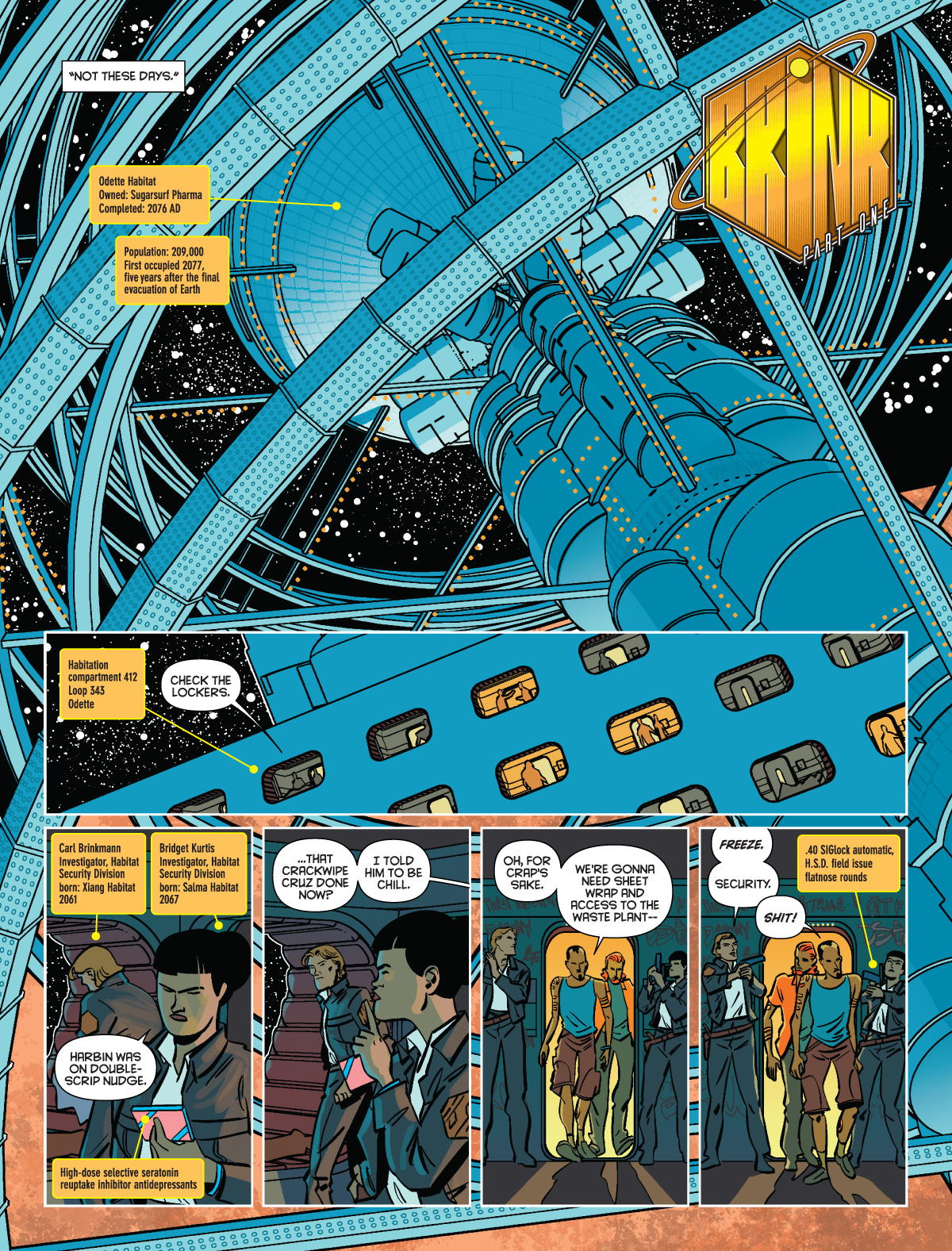

IAN: The basic design of a space corridor – they’re not identical between space stations but there are consistencies. I figured that in the face of impending doom everyone’s efforts to leave earth would have been relatively collaborative, reasonably cohesive, and so the sleeping bunks would be relatively alike. There’s little time to reinvent the wheel or worry about patents when you’ve got to go go go. So an ambi-grav unit will look familiar as you go from one station to another, stuff like that, but the light source on one station might be in the floor or ceiling and the next station will have light sources in the walls, as it does on Ludmilla.

DAN: I wanted everyone to talk like they meant it, to live in the world and never wonder at it (though WE might wonder at the spectacle of Ian’s exterior shots). It’s matter of fact, routine, almost dull to them. So it all became conversational, clipped. Far less emphasis in lettering (there are much fewer uses of bold than in my normal scripts). And no “Look at the size of that thing” awe moments, and certainly no “As you know, Bob…” conversations.

Brink is set in a far future in which humanity has been evacuated to a number of artificial habitats. What kind of research did you do to design these settings?

IAN: The key thing for me was really looking at the International Space Station and the way you have various components from different space programmes bolted together. So I had to factor in fuel, storage, arrays, service modules, airlocks and how they’d fit and work, and then just scale everything up to accommodate.

IAN: The key thing for me was really looking at the International Space Station and the way you have various components from different space programmes bolted together. So I had to factor in fuel, storage, arrays, service modules, airlocks and how they’d fit and work, and then just scale everything up to accommodate.

DAN: Between you and me, I think Ian just visited the future a few times and came back with sketches. I’d write “we see a large space station habitat” and he’d show me a real space station habitat, utterly believable. I found it better not to ask after a while.

Ian, space stations and police procedurals are both known for their muted palettes, but your work on Brink features a much wider range of colors. What inspired your approach to coloring Brink and Bridge’s world?

IAN: I looked at photographs of Tokyo at night. All the neon contrast. In fact, photography had a lot of influence for me over the look of the world of Brink. There’s also the photographs of subway cars in the ’80s covered in graffiti. Pull up any of those on a Google image search and you’ll see what I mean.

IAN: I looked at photographs of Tokyo at night. All the neon contrast. In fact, photography had a lot of influence for me over the look of the world of Brink. There’s also the photographs of subway cars in the ’80s covered in graffiti. Pull up any of those on a Google image search and you’ll see what I mean.

These two things set me on to realising that the aesthetic I was really going for all along was a sort of ’80s cyberpunk vibe, and this was after we’d already started and we were two episodes in, and so I took the first two parts of the story and redrew them, changing a whole heap of stuff from interiors to costumes, and going through the panels and tagging all the walls.

DAN: I think the colour was a great choice. Too much lo-fi SF is drab and stark. The colour gives this tiny, encapsulated world warmth… but also the hollow emptiness of advertisements.

Dan, there are eight million stories in the naked city, and it’s obvious that there are quite a few more to tell in Brink. How far ahead have you planned out the series, and can you give us an idea of what to expect?

DAN: I know what we’re doing as a second arc, but not much further beyond that.

DAN: I know what we’re doing as a second arc, but not much further beyond that.

One of the most enjoyable things about writing the series is that it is a genuine mystery. I’ve focused on the short-term clues, reveals and puzzles. It was only when I’d figured out this first ‘case’ that I knew where things had to go next. I think that’s the way this is going to work. I often plan series out in great length, way in advance. In this case, The Brink will keep hinting to me where to go next, following the clues, so I’m only a few steps behind. The surprises and twists come as a shock to me.

Can you each tell us a little about your other current and upcoming projects?

IAN: I’m going to be working on more Brass Sun with Ian Edginton and am going to be doing Doctor Who for Titan for two issues, written by Si Spurrier and Rob Williams. Dan and I also have a number of things we’re working on getting off the ground at the moment, so there’s plenty more to come.

DAN: Apart from my 2000 AD strips – Grey Area, Kingdom, Lawless and Sinister Dexter – I’m working on an epic Aliens/Predator/Prometheus/AvP event for Dark Horse called ‘Life and Death’ that’s running now. There’s also Hercules and Guardians of the Galaxy for Marvel, and DC’s Rebirth… for which I will be writing Aquaman, Titans and Earth 2. Huge fun.