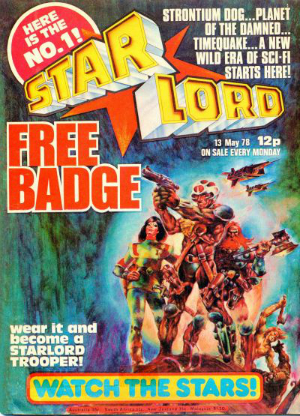

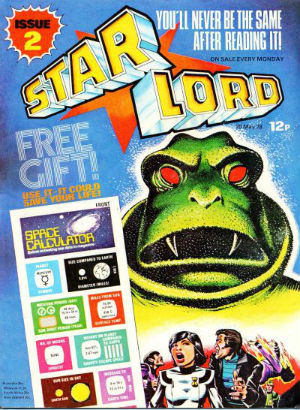

“Watch the stars!” screamed the cover of issue #1, cover dated 13th May 1978, and for the next six months readers did just that, courtesy of IPC’s classic science fiction weekly, Starlord! Launched a year after the seemingly immortal 2000 AD, but for some of us actually outshining it in almost every way at the time, Starlord had a fair bit going for it despite the dozens of titles still competing for space on newsagents’ shelves.

“Watch the stars!” screamed the cover of issue #1, cover dated 13th May 1978, and for the next six months readers did just that, courtesy of IPC’s classic science fiction weekly, Starlord! Launched a year after the seemingly immortal 2000 AD, but for some of us actually outshining it in almost every way at the time, Starlord had a fair bit going for it despite the dozens of titles still competing for space on newsagents’ shelves.

It had a staggering eight pages of full colour, a rare treat for those British readers more used to the meagre two-page colour centrespreads in 2000 AD, and the art which adorned those pages was simply gorgeous, somehow more ‘grown-up’ looking than that in most other comics of the time. As with 2000 AD, readers were invited to feel like part of an exclusive club by becoming ‘Star Troopers’, part of super-editor Starlord’s elite strike force against the evil Interstellar Federation (or ‘Int-Stell-Fed’) who, readers were assured, “cast their monstrous shadow across the entire universe”… at least according to Starlord himself, a big-haired, cape-wearing individual with unspecified powers and a disarming smile which seemed somewhat at odds with his regular grim warning messages!

It had a staggering eight pages of full colour, a rare treat for those British readers more used to the meagre two-page colour centrespreads in 2000 AD, and the art which adorned those pages was simply gorgeous, somehow more ‘grown-up’ looking than that in most other comics of the time. As with 2000 AD, readers were invited to feel like part of an exclusive club by becoming ‘Star Troopers’, part of super-editor Starlord’s elite strike force against the evil Interstellar Federation (or ‘Int-Stell-Fed’) who, readers were assured, “cast their monstrous shadow across the entire universe”… at least according to Starlord himself, a big-haired, cape-wearing individual with unspecified powers and a disarming smile which seemed somewhat at odds with his regular grim warning messages!

The first issue came accompanied by a free Star Trooper sticker (there were six different ones in all, prompting at least one sad individual… ahem… to purchase six copies in order to get them all) but prospective Star Troopers were warned not to place the sticker in contact with their bare skin, as it was mined from a special metal found on Axis 1A, and could give you an unpleasant skin disorder (funny — all of mine seemed to be made of paper…).

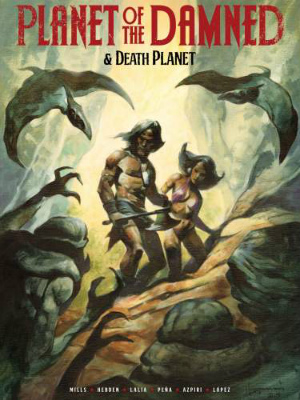

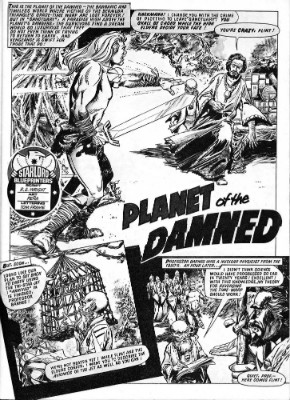

That first issue contained four stories in all, with a fifth, Mind Wars, beginning in #2. My personal favourite, I have to say, was probably Planet of the Damned by R.E. Wright (actually Pat Mills) and artists Horacio Lalia and later Alfonso Azpiri. To be honest, looking back, it’s hard to see why it made such an impression; the basic story, concerning a planeload of whinging gits drawn through an interdimensional warp in the Bermuda Triangle to a hellish world full of nightmare creatures, was hardly original, and the strip’s nominal hero (Jake Flint of the brig Gallantine, a survivor of a much earlier crossing) was basically just a poor man’s Tarzan.

Planet of the Damned (along with 2000 AD’s Death Planet) was reprinted last year by Rebellion. Available to order online here

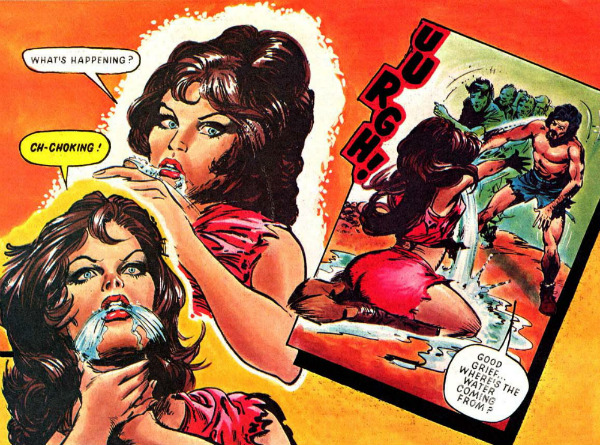

I think what attracted my attention at the tender age of eight was probably the imaginatively horrible ways in which most of the stricken travellers were offed (see below) during the strip’s run — lakes of poison, flesh-dissolving rain, killer plants, all things guaranteed to horrify the unwary parent who made the mistake of flicking through a copy! It was rather a shame, therefore, that Planet of the Damned was the only one of the original line-up of stories not to go the distance, ending in the tenth issue with Flint, writer Stan Hackman, and their few surviving colleagues escaping back through the portal to Miami (though what Miami made of Flint is unrecorded).

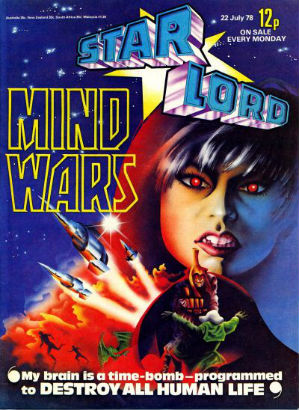

Rather more impressive in story terms was Mind Wars, masterfully and often wittily (in a wry sort of way) scripted by Alan Hebden and drawn for the most part by Jesús Redondo, who made scantily-clad heroine Ardeni Lakam (below) fuel for dozens of adolescent fantasies from the moment she made her first appearance in issue #2. Mind Wars is one of the forgotten classics of British comics, a minor masterpiece centred around psychic-powered twins Ardeni and Arlen, citizens of the human-dominated Stellar Federation (presumably not the same one Starlord was having so much trouble with) and the attempts of both their own government and the alien Jugla Empire to exploit them.

Full of twists and unexpected shocks (the most brutal being when Ardeni is forced to kill her brother Arlen to save humanity in issue #11, the serial’s mid-point) it is long overdue for reprinting and the conclusion, in which an irritated Ardeni warps herself and her friend Yosay Tilman off to parts unknown after disabling the weaponry of both space Empires, still stands up well today.

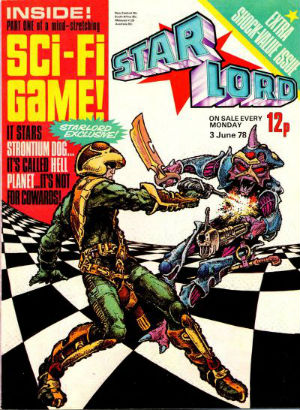

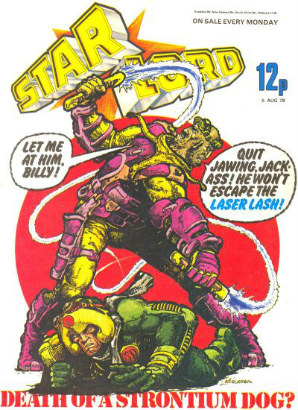

Strontium Dog, distinctively drawn by Carlos Ezquerra and written by Alan Grant, is of course the most successful strip to originate in Starlord, although these days it’s better known as one of the longest running strips in 2000 AD, where mutant bounty hunter Johnny Alpha and his ‘norm’ partner Wulf Sternhammer eventually ended up. Much has since been added to the legend of Johnny Alpha, including a large supporting cast and a complex backstory, but in these early tales it’s just the story of two guys bringing law to the lawless in a future that’s very like the old American West but with aliens, and it’s brilliant.

In recent years, after many odd and at times rather unwise divergences, 2000 AD have taken the taciturn Mr Alpha back to his roots and it’s been working pretty well — proof, if any were needed, that you just shouldn’t mess with a classic! And Johnny is still the coolest hero in comics: who else would at one point set his laser gun’s distance finder to shoot through his own head at a bad guy? (I’m still trying to figure out how that worked.)

Timequake (below left), created by Chris Lowder (writing as Jack Adrian) and Ian Kennedy (though some instalments were drawn by John Cooper) is another largely forgotten classic, though in this case what really makes it a classic is the art, which in some instances has an almost 3D quality to it. The actual story, about a group of ‘Time Control Agents’ (including brusque Londoner James Blocker, the strip’s hero) trying to stop the alien Droon and others from perverting the course of Earth’s history, is far from bad but the fact that Blocker (essentially a slightly less psychotic version of 2000 AD’s Bill Savage) is such a dull character stops most of it from being particularly memorable.

Still, it was a series with potential, even if it is sometimes rather worryingly reminiscent of 70s kids’ TV show The Tomorrow People. Possibly someone at 2000 AD thought it had potential too, accounting for the brief resurgence of Blocker and co. in that title some months after Starlord bit the dust. Either that, or they just needed another Starlord-originated tale in the comic which was still, at that point, titled 2000 AD & Starlord, and no other candidate was available…

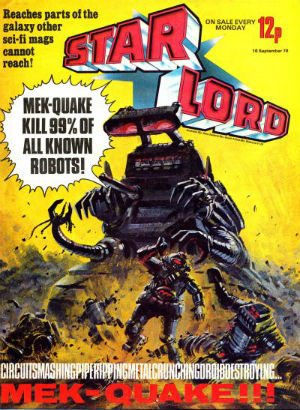

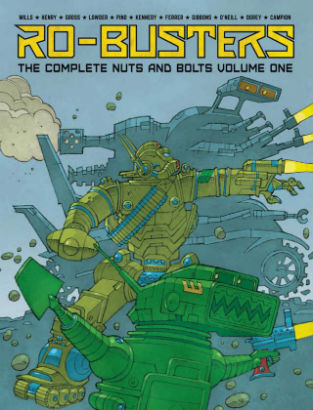

The remaining story in the original line-up was another that went on to bigger things in 2000 AD, and its two main characters would become among the most instantly recognisable in the 2000 AD stable: Ro-Jaws and Hammerstein, the forever bickering heroes of Ro-Busters, the everyday story of a bunch of clapped-out robots working as a disaster clean-up and rescue squad for the avaricious Howard Quartz (known as “Mr. Ten-per-cent” because only 10% of him — his brain — was still human). Ro-Busters, created by artist Carlos Pino and 2000 AD’s founding father Pat Mills, was the comedy element of Starlord: a riotous weekly romp in an insane mechanized world where robots did almost every job imaginable.

Redundant war droid Hammerstein (a stuffy, pompous character who was a parody of the heroes of a hundred 1950s war movies), disgraced sewer droid Ro-Jaws (funny, irreverent, and mouthy) and their colleagues, such as decommissioned construction droid ½ Tough, demented robot bulldozer Mek-Quake (with his distinctive battle cry of “Big jobs!”) and the insane medic Doctor Feeleygood, brought both humour and pathos to their delighted readers. Whether foiling a conspiracy in a futuristic hotel or saving a planeload of passengers from a robot pilot who believed he was fighting in the Battle of Britain, Ro-Jaws and Hammerstein never stopped wisecracking, and soon made Ro-Busters the title’s most popular strip.

The original Ro-Busters strips were recently collected by Rebellion (above right) and are available to buy online here

The only other ongoing strip in Starlord’s short life was Alan Hebden’s Holocaust, the replacement for Planet of the Damned, which began in the fourteenth issue. The story of a private investigator named Carl Hunter who discovered a covert alien invasion masterminded by the mysterious High Ones, it may not be the best strip ever written, but it more than stands up, not least because of Horacio Lalia’s art. The concluding chapter (in Starlord #22), in which the High Ones are revealed to be nothing more than telepathic rats, is wonderfully bonkers!

In fact, unlike the majority of comics anthologies, Starlord never really put a foot wrong — even fill-in stories like the brilliant ‘Good Morning Sheldon, I Love You’ in issue #11 (the story of a man trapped in a totally computerised house when the AI running it falls in love with him) and ‘Earn Big Money While You Sleep’ in #16 are pretty memorable, and since every ongoing story got some colour pages in rotation, they all got a chance to shine.

In fact, unlike the majority of comics anthologies, Starlord never really put a foot wrong — even fill-in stories like the brilliant ‘Good Morning Sheldon, I Love You’ in issue #11 (the story of a man trapped in a totally computerised house when the AI running it falls in love with him) and ‘Earn Big Money While You Sleep’ in #16 are pretty memorable, and since every ongoing story got some colour pages in rotation, they all got a chance to shine.

It’s a shame that after just 22 issues and one Summer Special, Starlord folded on 7th October ’78 and merged with its less flashy sister title 2000 AD the following week. Since Starlord was actually the better selling of the two comics despite its then exorbitant cover price of a staggering twelve pence, it seems this decision was entirely based on the fairly high production costs (aside from all the colour, Starlord was also printed on much higher quality paper than IPC’s other titles) rather than on Starlord’s assertion on the editorial page that he had driven off the Int-Stell-Fed and was now going to pursue them into space.

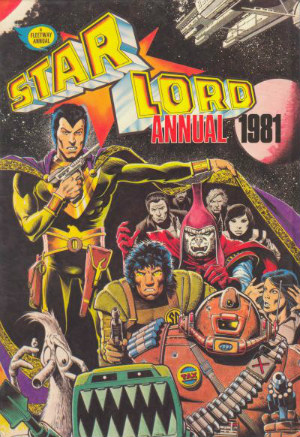

We still had Johnny and Wulf, of course, and Ro-Jaws and Hammerstein, but the demise of brilliant, bold, beautiful Starlord (the comic, not the idiot who looked like Alvin Stardust in a cape) was still a sad loss to Britain’s comics-reading kids… even if we did still get a Starlord Annual for the next three years.

Best Comic ever..This and 2000AD.

Planet of the Damned, ABC Warriors and Strontium Dog should be movies. Period!

Marvel and DC are way overated.

Great article..I miss these British masterpieces..