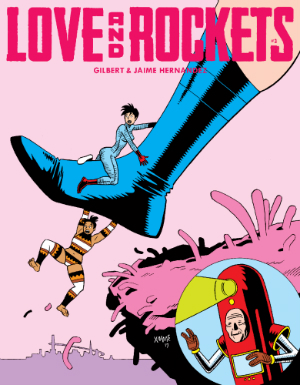

For all their differences in subject matter, illustrative style and setting, Los Bros Hernandez have one thing in common with their ongoing Love and Rockets epics: the history weighing down both the creators and their stories. At this point Jaime and Gilbert have been telling stories in their Locas and Palomar settings, respectively, for 35 years. In that period the assorted punks, luchadores and burn-outs of Hoppers have got together, split up, and grown old.

The family tree of ageing California transplant Luba has sprouted so many new branches it’s hard to identify them all (the very first Palomar story, “Chelo’s Burden,” was a six-page expository piece which introduced a good dozen characters with interconnected relationships, and it’s only grown more complex since then). Xaime and Beto, meanwhile, have switched the format of their life’s work from regular periodical to annual graphic novel series and now back again, have strayed for brief sojourns with the Big Two, have grown older alongside their cast and find themselves now occupied with filling in the blanks of their pasts because they now realise how much say that has in their futures.

The family tree of ageing California transplant Luba has sprouted so many new branches it’s hard to identify them all (the very first Palomar story, “Chelo’s Burden,” was a six-page expository piece which introduced a good dozen characters with interconnected relationships, and it’s only grown more complex since then). Xaime and Beto, meanwhile, have switched the format of their life’s work from regular periodical to annual graphic novel series and now back again, have strayed for brief sojourns with the Big Two, have grown older alongside their cast and find themselves now occupied with filling in the blanks of their pasts because they now realise how much say that has in their futures.

As with the previous two issues in this new run, the stories alternate between brothers, although each have a continuity in their use of flashbacks. On the Gilbert side of things, Baby remembers making amends with her mother Fritz after exploiting the family resemblance and imitating her mother in a porno. The issue opens with a Jaime story set in 1979, a young Maggie being groomed by a seedy local scenester, only for Isabel to swoop in and save her, before having words with a delinquent Hopey in the Belson Rec Centre. Skipping back to the present day, the young pair have grown older, the ageing process elegantly portrayed with just a couple of extra lines: a wrinkle at each side of Hopey’s mouth, an extra chin for Maggie.

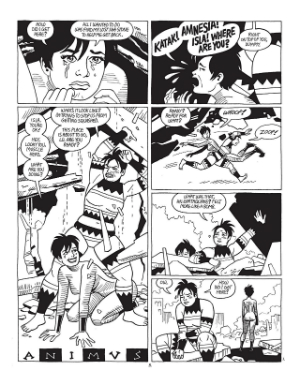

Before snapping back to reality, Jaime offers up another instalment of the sci-fi adventures of Princess Animus — introduced in New Stories — a throwback to the Fifties pulp he was inspired by with his early Love and Rockets stories of monsters and prosolar mechanics. His clear draughtsmanship and unfussy staging are as alien to contemporary genre comics as the rest of Love and Rockets is to the majority of the indie scene, more’s the pity.

Gilbert’s reference points for B-movie camp are evidently a little different, as Fritz’s daughters/”clones” are shown to have begun their acting careers as the regenerating assistant of a fictional Doctor Who knock-off called “Professor Enigma” (Quatermass gets a namecheck and all). Despite a note on the inside cover about the use of heavier black panel borders to indicate a flashback, Beto’s World remains the one where it’s most difficult to find purchase if you’re not entirely au fait with the granular detail of his serial, with its fractured timeline and purposefully similar-looking-characters (those caterpillar eyebrows, those dark eyes). Still, the gag of having his women concealing their Russ Meyer-approved breasts with a placard reading “MUST BE 18” hasn’t worn thin, and as with the Locas gang’s reunion at a punk gig, there is enough inherent sadness in shared nostalgia that’s recognisable even if the face’s aren’t. Even in “Professor Enigma” the characters come across a monstrous floating alien who doesn’t appear antagonistic, just “wistful.”

Gilbert’s reference points for B-movie camp are evidently a little different, as Fritz’s daughters/”clones” are shown to have begun their acting careers as the regenerating assistant of a fictional Doctor Who knock-off called “Professor Enigma” (Quatermass gets a namecheck and all). Despite a note on the inside cover about the use of heavier black panel borders to indicate a flashback, Beto’s World remains the one where it’s most difficult to find purchase if you’re not entirely au fait with the granular detail of his serial, with its fractured timeline and purposefully similar-looking-characters (those caterpillar eyebrows, those dark eyes). Still, the gag of having his women concealing their Russ Meyer-approved breasts with a placard reading “MUST BE 18” hasn’t worn thin, and as with the Locas gang’s reunion at a punk gig, there is enough inherent sadness in shared nostalgia that’s recognisable even if the face’s aren’t. Even in “Professor Enigma” the characters come across a monstrous floating alien who doesn’t appear antagonistic, just “wistful.”

Change is just one of the things that has set Love and Rockets apart from its comic book peers for the past 35 years. Mainstream books such as Judge Dredd, and pre-reboot Hellblazer are all talk when it comes to characters ageing in real time, serialised stories with real impact and so on, the comics of Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez are some of the only — Frank King’s Gasoline Alley and a couple other examples aside — where the passage of time has a tangible effect. Memory is one of the most important themes in Love and Rockets, and also one of the key skills if you’re hoping to keep up with the book. The characters have shed plenty since their introduction — jobs, relationships, residences — but they retain their memory. The reader must possess a decent one to make true sense of it all but perhaps, as with a long-running soap opera, or a superhero comic, your best bet is just to dive right in, let it wash over you. You’ll pick things up through context or flashback, start to figure things out, without having read the decades of stories that have come before them.

Change is just one of the things that has set Love and Rockets apart from its comic book peers for the past 35 years. Mainstream books such as Judge Dredd, and pre-reboot Hellblazer are all talk when it comes to characters ageing in real time, serialised stories with real impact and so on, the comics of Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez are some of the only — Frank King’s Gasoline Alley and a couple other examples aside — where the passage of time has a tangible effect. Memory is one of the most important themes in Love and Rockets, and also one of the key skills if you’re hoping to keep up with the book. The characters have shed plenty since their introduction — jobs, relationships, residences — but they retain their memory. The reader must possess a decent one to make true sense of it all but perhaps, as with a long-running soap opera, or a superhero comic, your best bet is just to dive right in, let it wash over you. You’ll pick things up through context or flashback, start to figure things out, without having read the decades of stories that have come before them.

The layouts, the linework, the staging — most often, characters in close up — remain as solid as they’ve ever been. What remains most gratifying about Love and Rockets over three decades in is the serialised nature of the stories. For all the time they spend picking over old wounds, the relationship between Hopey and Maggie still has enough space for fraught drama, for their shared history to spark conflict; the extended Palomar universe has been growing outwards like a kudzu for over thirty years, but there are still unexplored areas on the map Gilbert has been filling out. Issue three of this new series affirms, for all that this issue is about looking backwards, Los Bros Hernandez are moving ever forwards.

Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books, $4.99