Visually somewhere in the territory between Tekkonkinkreet and Henry Selick’s Coraline, the small in A Small Revolution can refer to the pre-teen anti-heroes at its heart. From the beginning, the mini-protagonist Florence and her frail but feisty friend Auguste are a joyfully contradictory mash-up of tropes. How much more self-consciously referential can you get than beginning a story with a plucky orphan leading a roof top chase after stealing a loaf of bread? Having escaped the clutches of the authorities, Florence lies back and lights up a cigarette. She’s more Cartman Constantine than Aladdin Don Juan.

Visually somewhere in the territory between Tekkonkinkreet and Henry Selick’s Coraline, the small in A Small Revolution can refer to the pre-teen anti-heroes at its heart. From the beginning, the mini-protagonist Florence and her frail but feisty friend Auguste are a joyfully contradictory mash-up of tropes. How much more self-consciously referential can you get than beginning a story with a plucky orphan leading a roof top chase after stealing a loaf of bread? Having escaped the clutches of the authorities, Florence lies back and lights up a cigarette. She’s more Cartman Constantine than Aladdin Don Juan.

First published in French in 2012, (as La Petite Revolution by Front Froid editions in Montreal) this English edition from Soaring Penguin brings together the Ignatz and Bédélys-nominated story for a wider audience. Seen from a child’s perspective (no matter how violent and foul-mouthed a child), the world Boum has created for her small revolution is appropriately small itself. The setting is not so much dystopian as storybook, with technology and architecture that is pretty much mid-twentieth century, but there is a small town isolationist feel that may be an actual tiny fascist state, or only one part of a bigger political struggle as localised through Florence’s eyes.

The faces are white and the names are French, but the everydayness of the setting implies this could be anywhere, anywhen. Luxuries that we mostly have access to now, such as hospitals and breathable air, are such things of historical hearsay to these street dwelling orphans, but this is not so hard to imagine. The author understands how normal life has a way of fitting within troubled times (she does mostly write autobiographical comics about living with small children after all, although technically I suppose her real babies don’t pre-date this her book baby).

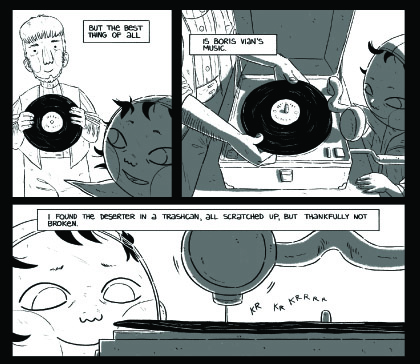

The only factor anchoring the story firmly to our world is a record that Florence is obsessed with – Le Déserteur (The Deserter) by Boris Vian from 1954. Lyrics from the song are interspersed with the story and serve as an interesting counterpoint to the revolutionary actions that the children become embroiled with. The song is about a French soldier refusing to fight, and yet Florence is desperate to fight. I enjoyed this very human contradiction, although I’m not a huge fan of overt musical references in comics.

You can enhance your reading of the book by finding the song and listening along, I wasn’t able (in my admittedly cursory googling) to find a satisfying English version however, so maybe just go for the mood if you don’t speak French. If you do hear or read the lyrics, the determined romantic bleakness of The Deserter might be seen to say all revolutions are small; all rebellions are ultimately personal and whether you join a cause or stand alone, it is the individual’s choice. How very un-liberté, égalité, fraternité.

And yet, Boum might make you think that the small revolutions are the most important ones of all. This elegantly sketched small world in which our anti-heroine lives and loves deeply holds our complex, unromantic, individualistic world accountable to a simple child’s perspective on justice. Embroiled in revolutionary activities that she knows she doesn’t really understand, Florence might just be the most important instigator in the development of this small dictatorship.

A Small Revolution is available here or from your local friendly comic retailer.

Boum (W/A) • Soaring Penguin Press, £8.99